According to federal data, strikes across Canada hit an 18-year high in 2023, accounting for over two million days not worked. This was the third successive year-over-year increase since the pandemic. It is a sign that, in the face of the current crisis, workers are radicalizing.

A ‘year of labour unrest’

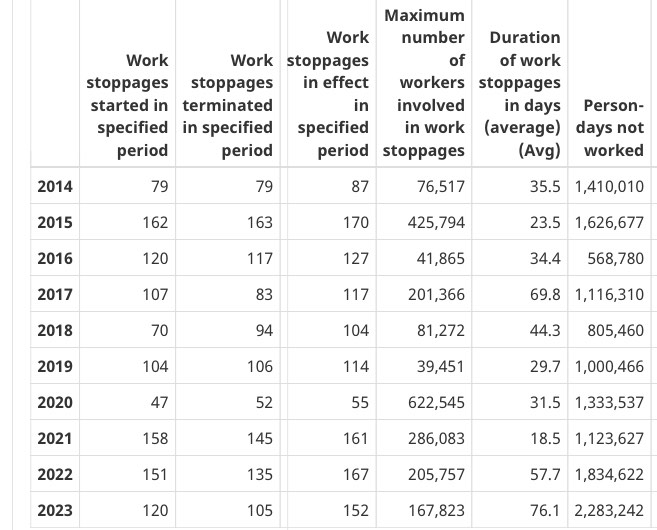

Strike statistics are again trending upwards. According to Statistics Canada, strikes through 2023 accounted for an 18-year high of 2.2 million person-days not worked.

While the data does not yet account for the recent Quebec common front strike of 600,000 public sector workers, the range of workers involved is already enormous. It covers seaway workers, grocery workers, autoworkers, airline workers, and education workers and more.

All told, last year’s 147 work stoppages accounted for the highest number of days not worked since 2005. In that year, strikes by Telus workers in B.C. and Alberta, along with strikes by education and social service workers in other provinces drove the number up to 4,147,580.

Not for nothing did CBC News call 2023 a “year of labour unrest” and “the year of the strike.”

Importantly, however, the 2023 data marks not just one increase in strike days but a sustained increase in strike days. Whereas most sustained rises over the past few decades have been followed by a fall in the number of strike days the next year, ever since 2019, they have only risen.

The data shows 1,000,466 person-days were “lost” to strikes in 2019, followed by 1,333,537 in 2020, 1,123,627 in 2021,up to 2,155,612 in 2022 and over 2.2 million in 2023.

Rising prices, rising shutdowns

As CBC News observed, this increase in strikes has closely followed the erosion of workers’ real wages, especially since the start of the pandemic.

According to the broadcaster, workers’ “purchasing power” remains “below where it was at the beginning of 2020.” This is a delicate way of saying the average worker has endured years of pay cuts, while the average boss has reaped billions more in profits.

In 2021 the average worker received a three per cent wage increase, against 4.8 per cent inflation. In 2022 wages grew by 5.1 per cent, against 6.8 per cent inflation. And, last year, inflation remained elevated at 3.1 per cent, while average wages still struggled to keep up.

Sell-out deals of one or two per cent became something of a norm in the 2000s, after years of betrayals and defeats. While there was never any enthusiasm in the union membership for these deals, in periods of low inflation they were comparably easier to tolerate, mostly meaning stagnation. But since 2020 and the “recovery” that has followed, the sell-out contracts of the past no longer merely mean stagnation: they mean cuts.

And this has forced the working class to fight.

A ‘domino effect’

On this point, various bourgeois outlets themselves expressed dismay at a “string of rejected agreements,” at workers “rejecting deals even their unions thought were good,” and at a “heightened environment for union militancy” throughout 2023. Human Resources Magazine further warned each such case of militancy risks causing a “domino effect,” whereby each struggle emboldens other struggles, across regions and across sectors.

A review of the year’s strikes finds they indeed have quite a lot to worry about.

For example, from February-August 2023, 250 Windsor Salt workers held out to block the company’s attempt to hold down their wages and contract out their work.

During the strike, the Windsor Salt workers rejected a tentative agreement with a wage offer of, according to the company, about six per cent over several years. The company called the offer “generous,” and it was endorsed by the Unifor leadership. But, nevertheless, it was rejected by striking workers themselves, who voted to remain on strike for another month after a total of 192 days.

In March, 120,000 federal public sector workers represented by PSAC launched one of the largest strikes in Canadian history. Rejecting a below inflation offer of 9 per cent over three years, the workers shut down huge sections of the Canadian economy for weeks, with widespread public support. Eventually, the PSAC leadership tried to pass-off a virtually-identical agreement of 12.6 per cent over four years, well below inflation and actively excluding CRA employees, who would be left to fend for themselves.

But this “deal” was met with a “vote no” campaign from a part of its membership and the union representing CRA staff. While the agreement was eventually ratified, it secured a fairly low vote of 76 per cent, reflecting clear discontent in the membership. And, during the ratification vote, the union was bombarded with messages from the rank and file. These workers insisted that they should “stay in the street” and stand in solidarity with the remaining workers on strike “since we ALL went on strike at the same time.”

In Vancouver, later in 2023, 4,000 ILWU members went on strike against wage erosion and job cuts, supported by their US counterparts. All told, the dockworkers brought over $6 billion in potential commercial activity to a halt, from July 1 until Aug 5. And, throughout, the workers stared down threats from the federal government, their bosses and the courts. During the course of the strike, moreover, they rejected a below-inflation tentative agreement of 19.2 per cent over four years, returning to the picket lines for weeks after.

Later that summer, in Ontario, 3,700 Metro grocery workers went on strike against wage cuts, precarity and abuse by management. While the Unifor leadership called off the strike in favor of a tentative agreement—which barely made up for the previous one’s cuts—it was quickly rejected.

At the time, the Toronto Star observed that the Metro strike is part of a “larger trend […] of lower-wage earners pushing back against employers for better pay in industries that have in recent years seen massive gains in profits.”

Finally, at the start of this year, 2,100 Air Transat flight attendants rejected by 98.1 per cent a tentative deal—hastily agreed to by their CUPE executive —and prepared to strike. After years of scraping by on a salary of $26,577 per year, the company’s offer—a reported 18 per cent over five years —would in all likelihood mean real cuts.

Militancy rebounds

The above cases certainly have their differences. But in all of them we see that more and more workers are rejecting the old methods of compromise.

The need to catch up with the rising prices has elicited a fighting mood across all sections of the working class. One can see it in increasingly high strike votes (typically around or over 95 per cent), in the length and depth of strike actions, or in the trend of workers refusing to back down and accept paltry wage settlements.

But this sentiment must be organized.

Naturally, workers are inclined to oppose contracts which in real or nominal terms cut their wages or benefits. But, unless an actual alternative is on offer, many will be eventually driven to bite the bullet and accept a mediocre deal.

At present, the labour movement is dominated by a leadership which, at bottom, accepts the right of the ruling class to rule. This fact conditions all other developments in the labour movement. From this premise flows strategies of compromise and conciliation over struggle. And, from this flows a tendency towards top-down management, which, for example, places the power to call and call-off strikes in the hands of “negotiating teams” and other tops instead of the rank and file.

But, at bottom, the system they accept cannot offer any permanent improvements.

By accepting the existence of capitalism and the rules of the capitalist state, reformist leaders can only, in the long term, erode their own base of support.

It is, crucially, inevitable that the present “recovery” will turn into a new slump in short order.

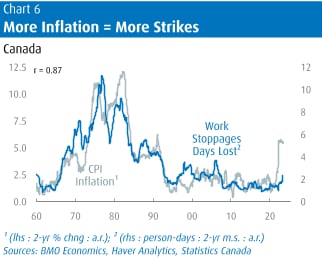

According to projections from BMO Capital Markets, a clear “softening” and even a stalling in the Canadian economy is bound to “take some steam out of wage gains.” From there, bourgeois economists are increasingly warning about a return to “stagflation,” a term coined to describe the crisis of the 1970s—one of sluggish growth and frantic price rises, punctuated by recessions and rising unemployment.

While we cannot predict exactly when the next slump will come, no one disputes its inevitability. Nor is it disputed that it will inevitably require new struggles to defend against the next bosses’ offensive.

On this point, BMO Capital Markets advised the ruling class: “We have long warned that the historical record shows that strike activity is highly correlated to inflation, with both reaching post-war extremes in the 1970s and early 1980.”

This peaked in the mid-1970s, when Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau complained that Canada was wracked by more strikes than any other industrialized country except Italy.

The task now is to unite all the layers of the working class and oppressed to defend against attacks, today and in the future.

Organize for revolution

The inflation that is eroding workers’ wages and lowering their living standards has, on paper, a number of causes: a combination of money printing, price shocks, protectionism, price gouging, wars and shut downs. But, at bottom, it results from the anarchy of the capitalist system and by the incompetence and stupidity of the capitalist class. It is their rule too, which makes crises inevitable.

So long as the capitalist class remains in power, new attacks are inevitable.

The only way to protect ourselves is, therefore, to build a revolutionary organization to topple the capitalist class and its state.

So long as the capitalist class rules, the enormous wealth of society—the food, the housing, the cars and other manufactured goods, which are produced and maintained by the working class— will be squandered in the interests of profit and mismanaged by the chaos of the market.

By toppling the capitalists and seizing this wealth, we can provide employment and a decent living for all, placing the wealth created by the working class under the control of the working class.