We are proud to announce a marxist.com exclusive! Here, we are making available online for the first time in English a brand new translation of a historic pamphlet written by Trotsky in 1904. Titled, Before the 9th of January, Trotsky shows how utterly reactionary the liberal bourgeoisie in Russia had become. He draws the important conclusion that the forthcoming revolution in Russia will find them in the camp of the enemy, and will instead be led by the revolutionary proletariat – a stunningly accurate prediction. As far as we are aware, this is available nowhere else in English online.

At the outset, we would like to give our special thanks to Maria Sverdlova for the enormous amount of work she put into translating this text from the original Russian.

[Wellred Books, the publishing house of the Revolutionary Communist International, publishes a wealth of texts by Trotsky, all of which are available to buy in print, digital or audiobook formats here]

Introduction by the editor of marxist.com

In a series of articles written in 1904, months before the outbreak of the Russian Revolution on 9 of January 1905 [Old Style], Trotsky boldly anticipated that the Russian liberals were totally unwilling to wage a serious struggle against Tsarism. He argued that, in order to accomplish the democratic tasks of bringing down the autocracy and convening a Constituent Assembly, the proletariat must play the leading role, and correctly predicted the revolution would begin with a general strike.

It is in these writings that Trotsky first began to formulate the key ideas that would lay the basis for his theory of Permanent Revolution. These articles were later collected as a pamphlet, titled Before the 9th of January, of which we have provided the first freely available English translation online!

Trotsky later explained the history of the pamphlet’s publication:

“Proceeding essentially from Plekhanov’s well-known position that the Russian revolutionary movement will win as a workers’ movement or not win at all, in 1904, on the basis of the experience of the violent strike movements of 1903, I came to the conclusion that Tsarism will be overthrown by a general strike, on the basis of which open revolutionary clashes will develop and expand, bringing decomposition into the army and pushing the best parts of it to the side of the insurrectionary masses.

“This pamphlet was handed over by me to the foreign publishing house of the Mensheviks, who at that time were still undecided on tactics and among whom an internal struggle was going on, with Martov defending the position of class against class (his programmatic article in the 1st issue of Sotsial-Demokrat), while Vera Ivanovna Zasulich and others defended the policy of agreement with the liberals and support for the bourgeoisie. Martov soon gave up his position and, with a few caveats, began to pursue the policy of Dan, who, for his part, had only slyly concealed Zasulich with scraps of Marxist phraseology. The Mensheviks delayed the printing of my pamphlet in every possible way, and when the 9th of January broke out in Petrograd, quite confirming the significance of a general strike, they declared the pamphlet obsolete.

“During proof-reading the brochure was looked at by comrade Parvus, who at that time held quite an internationalist revolutionary position. Parvus drew the conclusion that a revolution whose driving force is the working class and whose decisive methods are a general strike and uprising means the transfer of power to the workers in the event of the victory of the revolution. In this sense Parvus wrote the preface to my pamphlet, and together we insisted on its publication. It was published under the title Before the 9th of January.”

The articles were written against a backdrop of mounting crises for Tsarism.

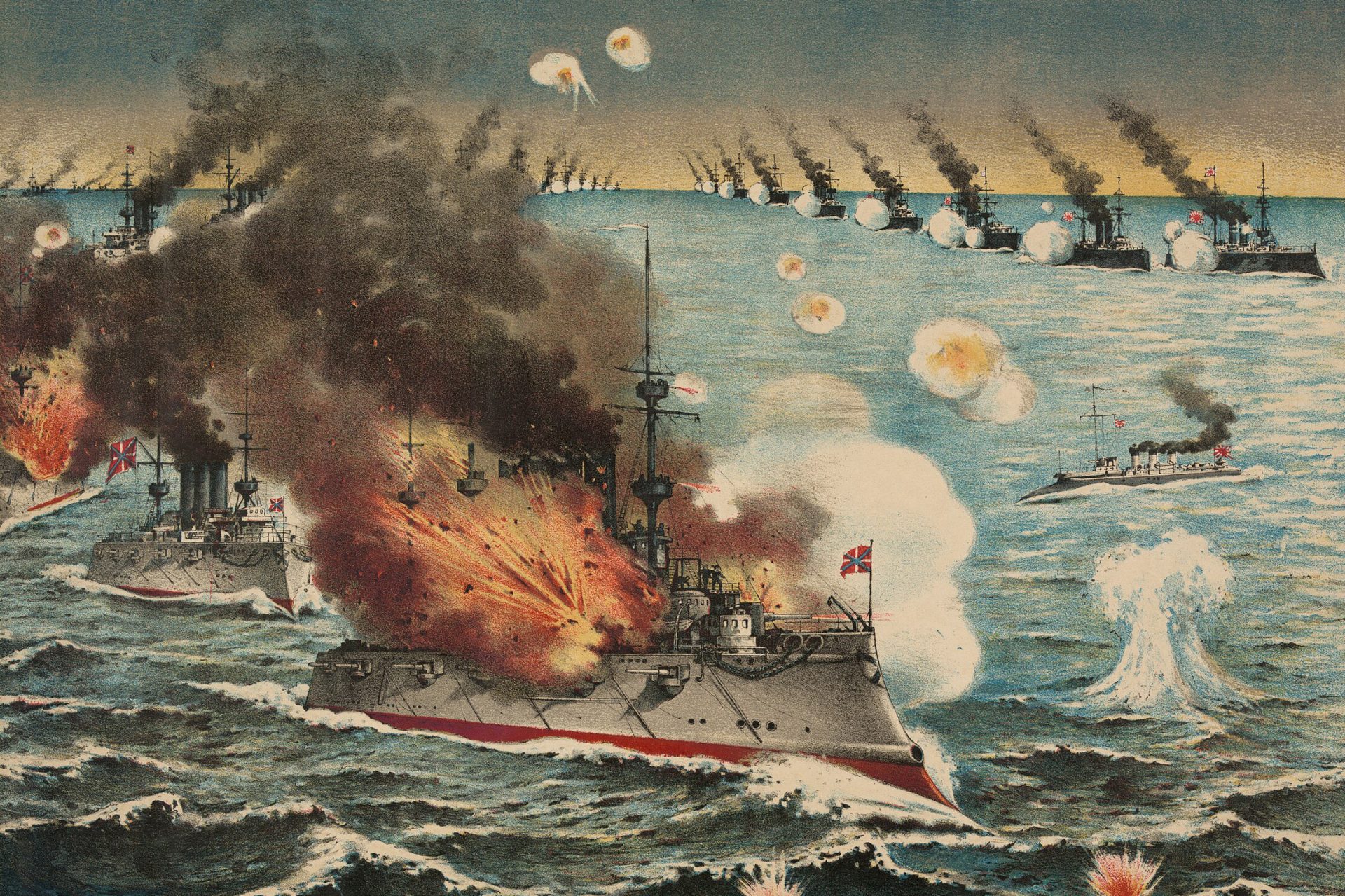

In February 1904, Tsarist Russia plunged into a disastrous war with Japan, arrogantly expecting an easy victory. The conservatives and liberals alike all dutifully rallied to the national flag and pledged their support for the war effort. But the Russian army and navy suffered a humiliating series of defeats, exposing the rottenness of the regime.

The war served to intensify opposition on the homefront. The liberals expressed their discontent through the organs of local government where they predominated, the zemstvos. They arranged a series of political meetings disguised as banquets across the country to discuss their demands.

Under the Minister of the Interior von Plehve, the regime clamped down on the zemstvos. But when he was assassinated and replaced with the liberal Prince Svyatopol-Mirsky, the zemstvos were allowed to organise a congress, as a means of relieving pressure on the regime. This congress, held in November, formulated a list of demands which included the right to free speech, assembly and a representative parliament. It stopped short, however, of demanding a constitution.

In December 1904, the Tsar issued a declaration promising to accede to some of these demands, but Tsarist absolutism, of course, remained untouched.

The first half of this pamphlet exhaustively proves the anti-democratic, anti-revolutionary nature of the so-called liberal opposition expressed through the many resolutions, speeches and articles issued from zemstvos, banquets and liberal newspapers. He also exposes the impotence of the ‘democratic’ intellectuals who clung to the coattails of the liberals.

However, the liberals were not the only ones in ferment. Russia’s young proletariat was beginning to discover its strength.

By the turn of the century, there were about 3 million workers in Russia, concentrated in massive factories. They began to seriously flex their muscles in 1903, with a wave of strikes particularly in the south of the country. The war served to fan the flames of discontent to previously inert and backward layers of the masses.

Trotsky’s pamphlet is absolutely scathing of the cowardice and treachery of Russia’s bourgeois liberals, which explains why the Menshevik-controlled Iskra editorial board delayed publication of these articles in 1904. After the 1905 Revolution, the position crystalised among the Mensheviks that because of the bourgeois democratic character of Russia’s coming revolution, the liberals were destined to lead it, with the workers playing a supporting role. The Mensheviks castigated the workers for going too far in 1905, thus ‘scaring off’ the liberals.

Trotsky countered that the servile and irresolute actions of the liberals meant that a revolution against Tsarist absolutism could only be carried out by the working class. He argued they would shove the liberals aside and pull the genuinely democratic forces in the country (peasants in rebellion, radical students and intellectuals) behind them.

Trotsky’s prognosis was confirmed in January 1905. A powerful strike was already underway at the Putilov Works (an artillery and railway plant) in St. Petersburg. On 9 January (Old Style), a peaceful procession of workers marched to the Winter Palace with a petition for reforms for the Tsar, only to be fired upon by armed cossacks. The massacre of ‘Bloody Sunday’ kicked off a wave of strikes across Russia that became general, and soon reached revolutionary proportions, forcing the Tsar to make promises of a constitution in a desperate bid to defuse the revolution.

Although 1905 turned out to be merely a dress rehearsal for an even greater revolution in 1917, centuries of absolutism was brought to the precipice by a worker-led revolution. The liberals played no active role in the revolution, and, as the revolution reached its culmination, passed over to playing an openly counter-revolutionary role.

In this remarkable text, especially its later parts under the subheadings Democracy and revolution and The proletariat and revolution, Trotsky predicts these features of the coming revolution. In the year of 1905, during which Trotsky played a leading role at the head of the St. Petersburg Soviet, the reactionary role of the liberal bourgeoisie and the leading role of the proletariat became crystal clear, as Trotsky himself predicted. In Results and Prospects, written while awaiting trial, Trotsky went further and concluded that only the proletariat could seize power, at the head of all the revolutionary layers of Russian society, and that once in power, it would not only complete the democratic tasks of the revolution, but would begin the socialist transformation of society. This pamphlet should thus be regarded as an important step towards the elaboration of this immortal theoretical conquest.

[Note on footnotes] We have translated all footnotes that were written in the original by Trotsky himself and marked them “[Trotsky]”. We have translated some of the footnotes from the footnotes, where they were found to be useful, by the editor of the 1925 Russian edition that this translation is based on, and have marked them “[Russian ed.]”. In some places we have also added our own footnotes where we thought clarification would be useful, and these are simply marked “[ed.]”.

Before the 9th of January

War and the liberal opposition

Let us look back at the past three months.

Prominent zemtsy[1] gather in St. Petersburg, hold a meeting that is neither secret nor public, and formulate constitutional demands. The intelligentsia hold a series of political banquets. Members of the district courts sit intermingled with returned exiles, members of the intelligentsia with red carnations in their buttonholes are interspersed with active state councillors[2], professors of state law sit side by side with workers under police surveillance.

The merchants of the Moscow Duma[3] express their solidarity with the constitutional programme of the Zemstvo Congress, the Moscow stockbrokers solidarise with the duma merchants.

Sworn attorneys organise a street demonstration, the political exiles agitate against exile in the newspapers, those under surveillance agitate against spies; a naval officer starts a journalistic campaign against the whole naval department, and when he is imprisoned the legal society collects money for his kortik[4].

The improbable becomes real, the impossible becomes probable.

The legal press reports on banquets, prints resolutions, gives accounts of the demonstrations, mentions in passing even the ‘well-known Russian proverb’,[5] and scolds generals and ministers – mostly, however, those already deceased or retired.

Journalists flounder, reminisce about the past, sighing, hoping, then warning each other against excessive hope; at a loss of what to do, they try to get away from slavish language but can’t find the words and end up being cautioned; they earnestly strive to be radical, wanting to call for something, but with no idea of what that something is; they utter many harsh words, but very hastily, because they are not sure of the future; behind sharp phrases they hide the feeling of uncertainty; everyone is confused, and each wants to make the others think that he is the only one not confused…

Now, this wave is receding… of course, only to immediately give way to another, higher wave.

Let us use this moment to take into account what has been done and said over the last period, and then draw a conclusion: what’s next?

The present situation, in the final analysis, has been created by the war. It is dramatically accelerating the natural process of the destruction of the autocracy, pulling lazy social groups onto the stage of political life with pincers and, as fast as it can, driving forward the formation of political parties…

In order not to lose all perspective, we need to step back a little from the period of the ‘spring’ turmoil – back to the beginning of the war, and at least cursorily review the policies of the various parties during this time of war on two fronts.

The war was presented to society as fact – all that remained was to make use of it.

The party of Tsarist reaction did everything it could in this regard. Absolutism, completely compromised as a representative of the interests of the nation’s cultural development, found the war to be an opportunity to show what seemed to itself and to others to be its strongest side. Taking advantage of this favourable circumstance, the reactionary press took on an aggressive tone and put on the order of the day slogans in which the autocracy, the nation, the army, Russia – all were united by the common interest of immediate victory.

“In no other thing,” repeated and still repeats Novoe Vremya,[6] “can a nation so consciously feel its unity as in its army. The army holds in its hands the international honour of the nation. The defeat of the army is the defeat of the nation.”

The task of reaction was thus clear: to turn the war into a national enterprise, to unite ‘society’ and ‘the people’ around the autocracy as the guardian of Russia’s might and honour, to create around Tsarism an atmosphere of devotion and patriotic enthusiasm. And reaction pursued this aim to the best of its ability and skill. It endeavoured to inflame feelings of patriotic indignation and moral outrage by mercilessly exploiting the so-called treacherous attack on our fleet by the Japanese. It portrayed the enemy as cunning, cowardly, greedy, petty, inhuman. It played on the fact that the enemy was yellow-faced, that he was a heathen. It endeavoured in this manner to arouse a surge of patriotic pride and a squeamish hatred of the enemy.

The events did not bear out the reaction’s predictions. The ill-fated Pacific fleet suffered loss after loss.[7] The reactionary press excused the failures by attributing them to accidental causes, and promised revenge on land. A series of land battles began, a series of monstrous losses, of retreats by the invincible Kuropatkin,[8] the hero of so many caricatures in the European press. The reactionary press endeavoured by the very facts of the defeats to injure the people’s pride and awaken a thirst for bloody vengeance.

During the first period of the war, the reaction organised patriotic demonstrations of students and urban rabble and covered the whole country with luboks,[9] in which the advantages of the Russian army over the Japanese were portrayed in the brightest colours available to patriotic painters.

When the number of wounded began to increase, the reaction urged support for the government-run Red Cross, in the name of patriotism and love of mankind; when the superiority of the Japanese fleet over ours became obvious, it encouraged the public to donate to the navy in the name of patriotism and public interest.

In short, the reaction did everything it could to make the war serve the interests of Tsarism, i.e., its own interests.

How did the official opposition, which held in its hands the organs of self-government – the zemstvos and the dumas – and the liberal press, act at this critical time?

Let us be blunt: they behaved shamefully.

The zemstvos not only obediently bore those war-related labours and expenses which were imposed on them by law; no, in addition to that they voluntarily came to the aid of the autocracy with their organisation of aid to the wounded.

This is a crime that continues to the present day – a crime against which no one in the liberal milieu has raised a voice of protest.

“If patriotic feeling urges you to take an active part in the calamities of war, go and feed and provide warmth for those who are shivering, treat the sick and the wounded,” taught Mr Struve,[10] sacrificing not to ‘patriotic feeling’ but to patriotic hypocrisy the last vestiges of his sense of opposition and political dignity. Is it not clear that at the moment when the reaction was creating the bloody mirage of a national cause, every honest opposition party should have recoiled from this cause as from a plague!

At the moment when the government’s Red Cross, which has sheltered in its ranks all the corrupt officials, is withering from a lack of funds, when the government is in the grip of financial need, the zemstvo appears and, using its authority as the opposition as well as public money, assumes a good share of the costs of the military adventure. Does it help the wounded? Yes, it helps the wounded, but it thus relieves the government of a part of the financial burden and facilitates its further conduct of the war and, therefore, the further creation of wounded people.

But this does not yet exhaust the issue, for the task is to overturn once and for all the order in which the senseless slaughter and maiming of tens of thousands of people hinges on the political passions of a gang of officials. The war has made this task all the more urgent by revealing the disgrace of Tsarism’s internal and foreign policy – policy that is senseless, predatory, clumsy, wasteful and bloody.

The reaction endeavoured – and, from the point of view of its interests, this was quite reasonable – to draw the whole nation materially and morally into the maelstrom of the military adventure. Where yesterday there still were groups and classes engaged in struggle – reaction and liberalism, the rulers and the people, the government and the opposition, strikes and repression – there, according to the reactions’ plan, a realm of national-patriotic unity was to be established at once.

The opposition should have exposed all the more sharply, energetically, daringly and ruthlessly the gulf between Tsarism and the nation, should have all the more resolutely tried to push the true national enemy, Tsarism, into this very gulf. Instead, the liberal zemstvos, with secret ‘oppositional’ desires (to seize into their hands a part of the military economy and make the government dependent on themselves!), harness themselves to the rattling military chariot, picking up the corpses, and wiping up the bloody tracks.

The matter, however, is not limited to donations towards aid organisations. Immediately following the declaration of war, the same zemstvos and dumas that are always complaining about their lack of funds suddenly donated ridiculous amounts of money for the needs of the war and the strengthening of the fleet. The Kharkov zemstvo snatched a whole million from its budget and put it at the direct disposal of the Tsar.

But even this is not all! The people of the zemstvos and dumas did not limit themselves to merely participating in the grunt work of the disgraceful slaughter and taking on a part of its expenses, i.e. passing it on to the people. They were not content with silent political connivance and tacit endorsement of Tsarism – no, they publicly declared their moral solidarity with the perpetrators of the greatest of atrocities. In a whole series of loyal addresses, the zemstvos and dumas, one after another and without exception, fell at the feet of the ‘imperious leader’ who had just trampled the Tver zemstvo[11] and was preparing to trample several others. They declared their indignation at the insidious enemy, religiously swore allegiance to the throne, and pledged themselves to sacrifice their lives and property – they knew they would never have to do so! – for the honour and glory of the Tsar and Russia. Behind the zemstvos and dumas trailed a disgraceful procession of professors’ corporations.[12] One after another, they responded to the declaration of war with loyal pronouncements, in which the scholastic ornateness of form harmonised with the political idiocy of the content. This series of servile displays culminated in the patriotic forgery by the Council of Bestuzhev courses, which vouched not only for its own patriotism but also for that of its students, who it never consulted on the matter.

To complete this ugly picture of cowardice, sycophancy, lies, petty diplomacy and cynicism, it will suffice, as a final brush-stroke, to mention that the delegation that presented the loyal address of the St Petersburg Zemstvo[13] to Nicholas II in the Winter Palace featured such ‘beacons’ of liberalism as Messrs Stasiulevich and Arseniev.

Should we dwell on all these facts? Should we comment on them? No, it is enough to name and establish such facts for them to burn as a slap on the political face of the liberal opposition.

And the liberal press? That wretched, mumbling, grovelling, lying, wriggling, corrupted and corrupting liberal press!… With a slavish longing for the Tsar’s defeat hidden in its heart, but with slogans of national pride on its tongue, it threw itself – without exception – into the filthy torrent of chauvinism, trying to keep up with the press of the reactionary thugs. Russkoye Slovo and Russkiye Vedomosti, Odesskiye Novosti, and Russkoye Bogatstvo, Peterburgskiye Vedomosti and Kurier, Rus’, and Kievskiy Otklik – all proved themselves worthy of each other. The liberal left, vying with the liberal right, spoke about the treachery of ‘our enemy,’ of his powerlessness and our strength, of the peace-loving nature of ‘our Monarch,’ of the inevitability of ‘our victory,’ of the completion of ‘our mission’ in the Far East – while not believing their own words and with a slavish longing for the Tsar’s defeat hidden in their souls.

Already in October, when the tone of the press had had time to change dramatically, Mr. l. Petrunkevich, the beauty and pride of zemstvo liberalism, the bogeyman of the reactionary press, assured the readers of Pravo that “whatever one’s opinion about the present war is, every Russian knows that once it has been started, it must not end at the expense of our country’s state and popular interests… We cannot offer Japan peace now and are compelled to continue the war until Japan agrees to peace terms that would be acceptable to us both from the point of view of our national dignity and from the point of view of Russian material interests”.

The ‘best’ and the ‘most dignified’ – all disgraced themselves equally.

“…The initial surging wave of chauvinism,” as Nashi Dni explains now, “not only met no obstacles on its way, but even carried away many leading figures, who apparently expected that its current would bring them closer to the desired shore.”

This was not an oversight, nor an accidental mistake, nor a misunderstanding. Here we see tactics, a plan. Here is the whole soul of our privileged opposition. Compromise over struggle. Rapprochement at all costs. Hence the endeavour to relieve absolutism of the emotional burden of this rapprochement. To organise not in the cause of fighting Tsarism, but in the cause of serving it. Not to defeat the government, but to entice it. To earn its gratitude and trust, to become indispensable to it. Finally, to bribe it with the people’s money. A tactic which is as old as Russian liberalism, and which has become neither cleverer nor any more honourable with time!

The Russian people will not forget that in a difficult moment the liberals did only one thing: attempt to buy for themselves the trust of the people’s enemy using the people’s own money.

From the very beginning of the war, the liberal opposition did everything possible to ruin the situation. But the revolutionary logic of events would not stop. The Port Arthur fleet was defeated, Admiral Makarov was killed, and the war spread onto land. Yalu, Kin-Chou, Dashichao, Wafangou, Liaoyang, Shahe[14] – all these are different names for the same autocratic disgrace. The Japanese army was smashing Russian absolutism not only on the seas and fields of East Asia, but also on the European stock exchange and in St. Petersburg.

The position of the Tsarist government was becoming more difficult than ever. Demoralisation in government ranks made consistency and resoluteness in domestic policy impossible. Fluctuations, attempts at reaching an agreement and appeasement became inevitable. The death of Plehve[15] provided a favourable occasion for a change of course.

Plehve’s place [as Minister of the Interior – ed.] was taken by Prince Svyatopolk-Mirsky.[16] He set himself the task of conciliation with the liberal opposition, and began this process of appeasement by expressing his confidence in the Russian population. That was foolish and arrogant. Is it up to a minister to trust the population? Not the other way around? Shouldn’t the minister depend on the trust of the public?

The opposition should have made Prince Svyatopolk understand this simple fact. Instead it began to fabricate addresses, telegrams and articles of gratitude and delight. On behalf of a population of one hundred and fifty million, it thanked the autocracy, which had declared that it ‘trusted’ a people who did not reciprocate this trust.

A wave of hope, expectation and gratitude surges through the liberal press. Russkiye Vedomosti and Rus’ join forces to wrest the Prince[17] from Grazhdanin and Moscovskiye Vedomosti, the district zemstvos express gratitude and hope, the towns express hope and gratitude; and now, after this policy of trust has already completed its full circle of development, the provincial zemstvos, one after another, send the minister belated votes of their reciprocal confidence… In this way the opposition prolongs internal turmoil and turns a silly political anecdote into a long-lasting political condition of a troubled country.

And once again a conclusion has to be drawn. The opposition, which failed to find its feet in such a favourable position, in which it was needed and fawned over; the opposition which responded to a single sign of governmental confidence with confidence of its own – has deprived itself of the right to any confidence whatsoever on the part of the people.

At the same time, it has deprived itself of the right to the enemy’s respect. The government, in the person of Prince Svyatopolk, promised to give the zemtsy the opportunity to convene legally, but did not fulfil this promise. The zemtsy did not protest and instead came together illegally. They took all possible measures to make their congress secret from the people. In other words, they did everything to deprive their congress of any political significance.

At their meeting on 7-9 November, the zemtsy – chairmen of provincial administrations and generally prominent figures of local self-government – formulated their demands. The zemstvo opposition, in the form of its most prominent, though not formally authorised, representatives, for the first time presented its programme to the people.

The conscious elements of the people have every reason to regard this programme with full attention. What do the zemtsy demand? What do they demand for themselves, and what for the people?

What do the zemtsy demand?

I. The right to vote

The zemtsy want a constitution. They demand that the people, through their representatives, participate in legislation. Do they want a democratic constitution? Do they demand that all people participate in legislation equally? In other words: are the zemtsy in favour of universal, equal and direct suffrage with secret ballots to ensure the independence of the vote?

The matter of universal suffrage does not exhaust the democratic programme, and calling for it does not yet make one a democrat – both because, under certain conditions, this demand can just as well be seized by reactionary demagogy, and because, for revolutionary democracy, universal suffrage is not just one of the demands, but an integral part of a comprehensive programme. But the converse statement – that without universal suffrage there is no democracy – is certainly true.

Let us look at how the zemstvo congress treated this cardinal democratic demand. We reread point by point all the resolutions of the congress – and nowhere do we find any mention of universal suffrage. This solves the question for us. We conclude: the programme of the zemtsy does not speak of universal suffrage, which means that the zemstvo opposition does not want universal suffrage.

Political mistrust is our right, and the entire history of the liberal opposition turns that right into our responsibility!

The zemstvo liberals care about their influence and political reputation. They have an interest in safeguarding themselves from criticism and exposure by social-democracy. They know that social-democracy has put forward the demand for universal suffrage and that it is vigilantly and suspiciously watching how the other opposition parties respond to said demand.

That is why the zemstvo liberals, had they stood for universal suffrage, would be obliged, in their own political interests, to print it in bold type in their programme. They did not do that. Which means they do not want universal suffrage.

One of the participants of the congress, ‘radical’ Mr Khizhnyakov, a member of the Chernigov zemstvo with a casting vote, argued at a meeting of the Kiev literary-artistic society that the resolutions of the zemstvo congress did not contradict the demand for universal suffrage. Mr Khizhnyakov reasoned scholastically. He either forgot or did not know that besides formal logic there is also political logic, for which omission is sometimes tantamount to rejection. And this was soon confirmed best of all by Mr Khizhnyakov himself, when he signed the resolution of the Chernigov zemstvo which demanded the convocation not of representatives of the people, but of representatives of the zemstvos and dumas. The congress did not go any further in its endeavours. With the vagueness of its wording, it was concealing the moderation and narrowness of its demands.

The resolutions of the congress do, however, contain one paragraph that gives reason to assert that the zemtsy not only did not reject universal suffrage, but even spoke in favour of it. The seventh paragraph says: “The individual civil and political rights of all citizens of Russia must be equal.”

Political rights are the rights to participate in the political life of the country, i.e. first of all the right to vote. The zemstvo congress decided that these rights should be equal for all.

In that case, wasn’t Vodovozov – another ‘radical’ – correct when, at the aforementioned meeting of the literary-artistic society, he objected in the following manner to the social-democrat who reproached the zemtsy for their omission of universal suffrage: “I unequivocally object to the speech of the disgruntled speaker. Paragraph seven speaks of the equality of individual civil and political rights. If you were more familiar with the science of statecraft,” said Mr Vodovozov, “you would see that this formula implies universal, equal, direct and secret suffrage!”

Mr Vodovozov is undoubtedly very familiar with statecraft. But he makes extremely bad use of his knowledge: he deceives his listeners.

Undeniably, equality of political rights, if taken seriously, means that citizens’ voting rights should be equal. But it is equally indisputable that paragraph seven limits this equality to male citizens, without extending it to female citizens. Or will Mr Vodovozov say that the zemtsy had women in mind as well? No, he will not say that. Thus, paragraph seven does not signify universal suffrage after all.

But it does not signify direct suffrage either. The electoral rights of citizens may be equal, but the constitution might give them the right to pick electors of the second degree, who in turn choose electors of the third degree, and the latter finally elect the ‘representatives of the people’. This system is deadly for the people, because it is easier for the ruling classes to influence a small circle of filtered electors than the masses of the people.[18]

Further, the equality of suffrage in itself says nothing about secret balloting. Meanwhile, this technical aspect of the matter is of enormous importance for all dependent, subordinate, economically oppressed strata of the people. This is especially true in Russia, with its age-old habits of despotism and slavery. With our barbarous traditions, a system of open voting could for a long time nullify the value of universal suffrage!

We have stated that it is only equal suffrage for men that logically flows from paragraph seven. But the zemtsy hasten to show that, contrary to the instructions of Mr Vodovozov’s statecraft, they do not bind themselves even to this obligation. The equality of political rights applies, of course, not only to the future parliament, but also to the zemstvos and dumas. Meanwhile, paragraph nine requires only that “the zemstvo representation should not be organised on the basis of estate, and that, if possible [sic!], all available forces of the local population should be involved in the zemstvo and self-government of the city”. Thus, the equality of political rights will only be applied “if possible”. The zemtsy explicitly speak out only against the estate-based census, but they fully allow for the “possibility” of a property-based census. In any event, there is no doubt that all those who do not fulfil any kind of permanent residency requirement – and such requirements by their whole character are directed against the proletariat – will still end up outside the boundaries of political equality.

So, contrary to the assurances of those who are ‘democrats’ out of opportunism and those who are ‘democrats’ out of political hypocrisy, paragraph seven does not in fact mean the universal, direct, equal or secret right to vote. In other words, it means nothing. It is a political flare meant to deceive simpletons and to serve as an instrument of deception in the hands of the opportunistic corrupters of political consciousness.

But even if the equality of political rights was as rich in meaning as Mr Vodovozov’s ‘science’ of statecraft wants us to think, we would still have to ask: did the zemtsy themselves invest these words with the content that said ‘science’ does? Of course not. If they really had democratic convictions, they would have been able to express them in a clear political form. It is not without reason, we would hope, that one of the secretaries of the zemstvo Congress, the Tambov radical Brukhatov, comments on paragraph seven in the democratic Nasha Zhizn’ by stating that “the people will receive the full extent of civil rights and the necessary [sic!] political rights”. The radical zemstvo spokesman and the democratic newspaper remain deliberately silent on the question of who is qualified to divide political rights into necessary and unnecessary…

Those who genuinely make democratic demands always count on the masses and appeal to them.

But the masses know nothing of the subtleties and sophistries of state law. They demand to be spoken to clearly, that things be called by their proper names, that their interests are protected by precisely worded guarantees and not left to the discretion of obliging interpreters.

And we consider it our political duty to help develop in the masses a distrust of that Aesopian language that has become second nature to our liberalism, which conceals not only political ‘untrustworthiness’, but also political unscrupulousness! …

II. The autocracy of the Tsar or the autocracy of the people?

What, then, would be the political system in which the liberal opposition considers the participation of the people necessary only ‘if possible’? Not only do the zemstvo resolutions say nothing about a republic – the mere connection of the zemstvo opposition with the demand for a republic sounds bizarre to the ear! – not only do they not speak of the destruction or restriction of the autocracy, they do not even say the word ‘constitution’ in their manifesto.

It is true that they speak of “the proper participation of the popular representation in the exercise of legislative power, in the establishment of the state’s revenue and expenditure accounts, and in the control over the legality of the administration’s actions” – therefore, they are referring to the constitution. They are only avoiding calling it by its name. In that case, is this something worth dwelling on?

We think it is. The European liberal press, which hates the Russian revolution just as much as it sympathises with Russian zemstvo liberalism, pauses with delight before this tactful omission by the zemstvo declaration: the liberals have managed to express what they wanted, avoiding at the same time the use of words that could have made it impossible for Prince Svyatopolk to accept the zemstvo’s decisions.

This constitutes a perfectly correct explanation of why the zemstvo programme says nothing not only about the republic, which the zemtsy do not want, but also about the ‘constitution’, which they do want. In formulating their demands, the zemtsy had in mind only the government with which they must come to an agreement, and not the mass of the people to whom they could appeal.

They were working out the terms of a commercial and political compromise, not directives for political agitation.

They did not for a moment abandon their anti-revolutionary position – and this is clear not only from what they say, but also from what they omit.

While the reactionary press insists day after day that the people are devoted to the autocracy, and incessantly repeats – through Moskovskiye Vedomosti – that the ‘true’ Russian people not only have no wish for a constitution, but that they do not even understand this foreign word – the zemstvo liberals do not dare to utter this word and thereby bring it to the attention of the people. Behind this fear of the word lies the fear of the deed: the struggle, the masses, the revolution.

We repeat: anyone that wants to be understood by the masses, that wants them to support him, must first and foremost express his demands clearly and precisely, call everything by its proper name, call a constitution – a constitution, a republic – a republic, universal suffrage – universal suffrage.

Russian liberalism in general and zemstvo liberalism in particular has never broken with the monarchy and is not breaking with it now.

On the contrary, it endeavours to prove that it is in itself, in liberalism, that the monarchy’s only salvation lies.

Prince S. Trubetskoy writes in Pravo:

“The vital interests of the Throne and the people require that the bureaucratic organisation does not usurp full power, that it ceases to be virtually uncontrolled and irresponsible… And this, in turn, is possible only with the help of an organisation standing outside the bureaucracy, with the aid of a true rapprochement of the people and the Throne – the living centre of power”.

The zemstvo Congress not only refused to renounce the monarchical principle, but based all its resolutions on the “idea” of the throne as “the living centre of power”, as formulated by Prince Trubetskoy.

Popular representation is put forward by the congress not as the only means of taking the people’s affairs into their own hands, but as a means of uniting the Sovereign Power with the population, currently separated from each other by the bureaucratic system (paragraphs three, four and ten). It is not the absolute power of the people that is opposed to the autocracy of the Tsar, but only popular representation counterposed to the Tsarist bureaucracy. The “living centre of power” is not the people, but the throne.

III. Who holds constitutive power?

This pathetic point of view, this seeking to reconcile Tsarist autocracy with popular rule, expressed itself in the completely treacherous answer to the question: by whom, and how, will that state transformation be carried out which was characterised, with such ominous uncertainty for the people, in the resolutions of the zemstvo congress?

In the last (eleventh) paragraph of its decisions, the Council (this is what the zemstvo congress calls itself) expresses its “hope that the Supreme Power will call upon the freely elected representatives of the people in order to, with their assistance, lead our fatherland onto a new path of state development in the spirit of the establishment of the principle of law and of the interaction between the state power and the people.” This is the path down which the opposition wants to direct the matter of Russia’s state renewal. The Sovereign Power must call to its aid the representatives of the people. The resolution, even here in this decisive paragraph, does not say anything about who said people are.

Meanwhile, we have not forgotten that in the ‘Programme of the Russian Constitutionalists’, which Osvobozhdeniye[19] declared to be its own programme, the role of such representatives of the people is taken to be the duma and zemstvo deputies, who “essentially represent the ground floor of the future constitutional building”… “By necessity,” – says the ‘Programme’, – “one has to follow historical precedent and leave this preparatory work in the hands of the representatives of the existing institutions of public self-government… This way is more certain and better than that ‘leap into the unknown’ which any attempt at ad hoc elections for a given case would represent, under the governmental pressure that is inevitable in such cases and taking into consideration the difficult-to-define mood of social strata unaccustomed to political life.”

But, let us further assume that the representatives of these qualified ‘people’ do assemble and begin the work of the Constituent Assembly. To whom does the decisive voice in this work belong: to the Throne – “the living centre of power” – or to the people’s representatives? This question decides everything.

The resolution of the Council says that it will be the Supreme Power, assisted by the popular representatives it calls upon, that will lead our fatherland onto a new path. Thus, the zemstvo Council confers the constituent power on none other than the Crown. The very idea of a National Constituent Assembly as the supreme authority is here completely eliminated. In establishing the ‘foundations of law’ the Crown enjoys the ‘assistance’ of the people’s representatives – but if it comes into conflict with them, it can just as well do without their assistance, and send them away through the same gates through which they were summoned.

It is precisely this organisation of constitutive power and this way of constitution building that the resolution of the zemstvo council indicates. We need not create any illusions in this respect. And really, such a solution to the question pre-emptively puts the entire fate of the Russian constitution at the discretion of the Crown!

In the period of constitutive work, as in any other period, there can only be one ‘Supreme Power’ – it can belong either to the Crown or to the Assembly. Either the Crown working with the co-operation of the Assembly, or the Assembly working against the opposition of the Crown. Either the sovereignty of the people or the sovereignty of the monarch.

One may, of course, endeavour to interpret the eleventh paragraph of the resolution of the zemstvo council to mean that the Crown and the assembly of representatives, as two independent and therefore equal powers, could enter into a constitutional agreement. This is the most favourable assumption one could make about the zemstvo resolution. But what would come out of it? The Crown and the Assembly are independent of each other. Each side has the right to say yes or no to the other’s proposals. But this also means that the two parties entering into negotiations may not come to any agreement.

Who will have the casting vote in such a case? Who will arbitrate? The assumption of two equal parties brings us to an absurdity: in the case of conflict between the Crown and the people – and such conflict is inevitable – we are in need of an arbitrator. But life never stops in the face of a legal impasse. It always finds a way out.

And this way out, in the end, will be a revolutionary proclamation of the supremacy of the people. Only the people can play the role of arbitrator in their own struggle with the Crown. Only a National Constituent Assembly – not only independent from the Crown but possessing power in its entirety, holding in its hands the keys and lockpicks of all rights and privileges, and the right of categorical decision on all matters, including the destiny of the Russian monarchy – only such a sovereign Constituent Assembly will be able to freely create a new democratic law.

That is why an honest and consistent democracy must tirelessly and irreconcilably appeal – not only over the head of the criminal monarchy, but also over the narrow-minded heads of those representatives of the qualified people that the monarchy calls upon ‘for assistance’ – for the all-powerful will of the people, expressed in a Constituent Assembly via a nationwide, universal, direct and secret ballot.

Does anyone need to be reminded that the zemstvo programme does not address the agrarian and workers’ questions at all? It evades them so easily, as if these questions did not exist in Russia…

The resolutions of the zemstvo council of 7, 8 and 9 of November are the highest achievements of zemstvo liberalism. In the subsequent provincial zemstvo meetings, liberalism takes several steps back from the November resolutions.

Only the provincial zemstvo of Vyatka signed on to the programme of the zemstvo Council in its entirety.

The provincial zemstvo of Yaroslavl “firmly believes” that Nicholas “will wish to call upon the elected representatives to work together” – in order to “bring the Tsar closer to his people” – “in accordance with the principles of ‘greater’ [!] equality and personal inviolability”. “Greater” (than at present) equality for the Tsar’s people does not rule out, of course, political nor even civil inequality.

The Poltava zemstvo repeats in its address the tenth paragraph of the resolution, which mentions “the proper participation of people’s representatives in the exercise of legislative power”, but does not say a word about ‘political equality’ or the forms of ‘popular representation’.

The Chernigov zemstvo “most loyally requests His Majesty to hear the sincere and truthful word of the Russian land, for which purpose he should summon the freely elected representatives of the zemstvo and command them [!] to independently and autonomously draw up a draft of reforms… and permit them [!] to submit this draft directly to His Majesty.” Here “representatives of the zemstvo” are clearly and openly named as representatives of the “Russian land”. The Chernigov zemstvo asks that these representatives be given only an advisory vote, only the right to outline and submit a draft of reforms. In addition, the Chernigov zemstvo “most loyally requests” that the representatives of the Russian land be commanded to be independent and autonomous!

The Bessarabian zemstvo requests the Minister of Internal Affairs to convene the “representatives of provincial zemstvos and the most important cities of the Empire for joint discussion” of the proposed reforms.

The provincial zemstvo of Kazan “deeply believes that in the search for ways to implement the will of the autocratic power, the representatives of the zemstvo freely elected for that purpose will not be deprived of their votes.”

The Penza zemstvo expresses its “loyal and unbounded gratitude” for the reforms outlined in the Tsar’s decree and, for its part, promises “zealous service… in the vast sphere of local improvements.”

The Petersburg zemstvo, on the initiative of Mr Arsenyev, who signed, among others, the resolutions of the zemstvo council, proposes to initiate a petition requesting that “the representatives of zemstvo and municipal institutions be allowed to participate in the discussion of government measures and bills.”

The Kostroma zemstvo requests that projects concerning zemstvo life should be discussed by the zemtsy beforehand.

Other zemstvos confined themselves to loyal gratitude for the Tsar’s decree[20] or a request to Prince Svyatopolk to “preserve the precious vow of trust in his soul.”

For now, that is the end of the opposition campaign of the zemstvos.

The democracy

We have touched upon the behaviour of the reaction and dwelt more closely on the behaviour of the bourgeois-noble opposition. Now we must ask: where was the democracy?

We do not mean the masses of the people, the peasantry and the urban petty bourgeoisie, who – especially the former – represent a huge reservoir of potential revolutionary energy, but who still play too little a conscious part in the political life of the country. We have in mind those broad circles of the intelligentsia who see their calling in the formulation and representation of the political demands of the country. We have in mind the representatives of the liberal professions, the doctors, lawyers, professors, journalists, of the the third element[21] of the zemstvos and dumas, namely, the statisticians, physicians, agronomists, teachers, and so on and so forth.

What was this democratic intelligentsia doing?

Apart from the revolutionary students – who honestly protested against the war and, contrary to the shameful advice of Mr Struve, shouted not, ‘Long live the army!’ but, ‘Long live the revolution!’ – the rest of this democracy was weary with the knowledge of its own impotence.

These democrats saw two choices before them: either to get closer to the zemstvos, in whose political strength they believed – but at the cost of the complete rejection of any democratic demands; or to come closer to a democratic programme – at the cost of breaking with the most ‘influential’ of the zemstvo opposition. Either democratism without influence, or influence without democratism. Because of their political limitations, they did not see the third way: to unite with the revolutionary masses. This option offers strength and, at the same time, it not only allows, but requires the development of a democratic programme.

The war caught the democracy in a state of total impotence. It did not dare oppose the ‘patriotic’ bacchanalia. From the lips of Mr Struve it shouted: ‘Long live the army!’ and expressed the conviction that ‘the army will fulfil its duty.’ It gave its blessing to the zemstvos supporting the autocratic adventure. It reduced its opposition to the cry: ‘Down with von Plehve!’ It kept hidden its democratism, its political dignity, honour and conscience. It tailed the liberals, who, in turn, followed the reaction.

The war continued. The autocracy suffered blow after blow. A black cloud of terror hung over the country. The elements for a spontaneous explosion were accumulating at the bottom of society. The zemstvos did not take a single step forward. Then, the democrats appeared to become more self-aware. In Osvobozhdeniye, there appeared insistent speeches about the need for independent organisation on the basis of a ‘democratic platform’. Occasional voices against the war could be heard. This natural process was interrupted by the assassination of Plehve and the change in the government’s course, which caused an unusually rapid rise in the zemstvo opposition’s political activity. Happiness began to seem so possible, so near…

The zemtsy put forward the programme discussed above – and the democrats began praising them unanimously and with great enthusiasm.

In the zemstvo resolutions, they found an expression of their own democratic demands and readily proclaimed the zemstvo’s decisions to be their own.

Osvobozhdeniye stated that “although the zemstvo congress consisted exclusively of landowners – primarily from the privileged gentry – its resolutions do not bear any imprint of class or estate[22] and on the contrary, are imbued with a purely democratic spirit.”

The whole left wing of our liberal press just as solemnly proclaimed the democratic spirit of the zemstvos.

Based on the November resolutions, Nasha Zhizn’ declared the full convergence of the zemstvo-liberal and democratic tendencies.

“This old and terrible ulcer on Russian life,” says this newspaper, “the spiritual and cultural divergence of the people and the intelligentsia… can only be cauterised by the heroic means of democratic state-building”. The zemtsy understood this, leading them to commit firmly to “a common platform with the democratic intelligentsia. This is an event of historical significance. It marks the beginning of a social-political collaboration that could have enormous significance for the destiny of our country.”

Syn Otechestva, which first appeared during the time of the ‘Minister of trust’[23] but was soon slaughtered by none other than said minister, began its short life by proclaiming that “the notable characteristic of the historic moment we are living through is the radicalism of the political tendencies that exist in our country”. This paper accepted the programme of the zemstvo congress in full. It recommended that representatives of the cities “take the same true and glorious path that the zemstvo people have already taken with such success before them, and repeat word for word, point by point, everything that has been and is being said so clearly, eloquently, coherently and with such dignity and strength by the representatives of zemstvo Russia”.

In a word, the democracy calls upon each and all to rally around the zemstvo banner. It does not see any tears or stains on this banner. And so we ask: can the people trust such a democracy?

Are we to give them a vote of confidence, view their omissions as accidents, interpret their evasions in a democratic spirit, and shout that ‘today there are no more of those disputes or disagreements that still existed yesterday’ – are we to do all this for the sole reason that, in a moment of excitement, under pressure from below and with somewhat of ‘permission’ from above, the zemtsy scribbled their vague constitutional programme onto a piece of paper?

Kind sirs! These are tactics of those who betray the democratic cause.

After 7 November 1904 there will be many more decisive moments in the struggle for liberation – and the task of the zemstvo opposition will not always be limited to merely outlining constitutional resolutions under the unofficial protection of Svyatopolk-Mirsky.

Can we have any confidence that the zemstvos will rise to the occasion? If our history teaches us anything, if we do not believe in miraculous transformations, the answer must be: definitely not! Trust in the democratism and oppositional steadfastness of the zemstvos is not our policy. What we must do at once is rapidly assemble the forces that we could lead into the arena against the all-Russia zemstvo at that decisive moment when it starts trading its lighthearted opposition for the real gold of political privileges.

But no, instead of rallying forces around implacable democratic slogans, we are supposed to sow confidence in the democratism of the liberal leadership, to swear left and right that the zemtsy are committed to the fight for universal suffrage, to insist that ‘yesterday there were still some disagreements, but today there are none!’

None?

Does it mean that the zemtsy led by Mr Shipov, or those led by Mr Iv. Petrunkevich, have recognised that it is only the people that can radically liquidate the autocratic economy and build the foundations for a democratic system on Russian soil? That the zemtsy have given up on the hope of the monarchy making compromises? That the zemtsy have stopped their shameful cooperation with absolutism in the sphere of military adventures? Or that the zemtsy have agreed that the only path to freedom is the revolutionary path?

Not only is it not possible for the conscious elements among the people to have political trust in the anti-revolutionary, estate-based opposition, they will not succumb, not even for a minute, to illusions concerning the ‘democratism’ of that unstable and confused democracy that only knows one slogan: that of merging with the anti-revolutionary and anti-democratic zemstvo opposition.

A classic example of democratic confusion, inconsistency and hesitation is the resolution worked out by a meeting of the Kiev intelligentsia for the consideration of the zemstvo congress.

“…The meeting dwelt on this question: what must the congress of representatives of the zemstvo say regarding the necessary reforms? The meeting concluded that this congress, made up of people who have come together on their own initiative, has no right to regard itself as the spokesperson for the wishes of the people. Therefore, the congress is obliged first and foremost to announce to the government that it does not consider itself competent to submit a finished reform project, but instead recommends convening an assembly of the people’s representatives, elected by universal (equal?), direct and secret balloting. It is this kind of Constituent Assembly that will, after discussing the present situation, have to propose (?) a reform project.”

Isn’t this energetic, decisive and clear? But let us proceed.

“If the government refuses to convene such an assembly, then the congress must present a certain minimum of political demands accepted by everyone… Some thought that this minimum should consist of demands for: personal freedom, freedom of conscience, of speech and the press; freedom of assembly, public associations, and the right to convene a legislative assembly consisting of elected representatives of the zemstvos and the cities… Another layer of congress attendees found this kind of legislative assembly not compliant with the principle of universal suffrage and expressed concerns that a constitution built on such foundations would indefinitely delay the possibility of introducing universal suffrage. This group of attendees found it more appropriate for the congress of representatives to limit itself to the demands for personal freedom, freedom of conscience, speech and the press, alongside freedom of assembly and public association… Then, the congress as a whole agreed that it is necessary to restore the zemstvo Statute of 1864.”[24]

Such is the voice of the ‘democracy’.

A nation-wide Constituent Assembly must be demanded. If the government does not agree, however, a council of aristocrats and merchants will be enough. We can ask for universal suffrage, but we will settle for suffrage with rank and property qualifications. The Kiev intelligentsia’s resolution essentially says that if the autocracy wants to get rid of the demand for a nation-wide Constituent Assembly, it is enough for it to respond to us by saying: I do not agree to this demand – and we, in turn, will easily settle (only temporarily, of course!) for representation of the zemstvos and dumas!

The Kiev congress printed its resolution. It did not keep it a secret from Prince Svyatopolsk-Mirsky. Does the Kiev intelligentsia not think that by doing so, it is giving the government very authoritative guidance on how democratic demands can be shelved without fuss or complication: it can just refuse to accept them. Can there be any doubt that the government will immediately act on this advice? In order not to set out on the easy path that is being recommended to it, the autocracy would itself have to value universal suffrage. In other words: it would have to be more democratic than the authors of the resolution. This is, of course, impossible.

In that case, what does the entire first part of the declaration, which so clearly and categorically denies to the zemstvos any right to speak in the name of the people, and which so decisively advances the demand for universal suffrage, constitute? Nothing but empty democratic phrase-mongering, with the aid of which the Kiev intelligentsia reconcile themselves to their actual abandonment of democratic demands. But, having betrayed from the very outset the political rights of the masses, the Kiev ‘democracy’ gets absolutely nothing in return: it still does not have an answer to the question – what happens if the autocracy, seduced by an easy victory over democratic demands, later refuses to accept the minimum of constitutional demands that the authors of the resolution do not want to give up on?

This resolution, which was adopted in Kiev, the centre of the ‘left-wing’ Osvobozhdentsy, is by no means an exception. Resolutions passed by other democratic banquets differ from the Kiev one only in that they do not ask the question: what is to be done if the autocracy does not approve the democratic programme? – just as the zemstvo liberals have nowhere yet answered the question: what is to be done if the autocracy does not accept their programme of suffrage with property qualifications?

Democracy and revolution

The only true democracy under conditions of absolutism is revolutionary democracy. A party that, on principle, advocates for peaceful means – the activity of which is aimed at compromise and not revolution – in Russia’s political conditions, such a party cannot be a democratic party. This is indisputably clear. Absolutism may enter into certain agreements, make one concession or another, but the goal of these concessions will always be self-preservation and not self-destruction. This predetermines the political weight of said concessions and the democratic value of reforms.

The government may summon representatives of the people, or at least their more compliant elements, in the calculation that they can be transformed into a new pillar of support for the Tsarist throne. Democracy, if it is true to its name, demands unlimited popular rule. It counterposes the sovereign will of the people to the sovereign will of the monarch. It counterposes the collective ‘we’ of the people to the individual ‘I’ of divine right.

But, in counterposing the will of the people to that of the monarch, a democracy that believes in its own programme must understand that its real task lies in opposing the power of the people to the monarch’s power. And such an opposition means revolution. Faced with absolutism struggling for its existence, democracy that believes in its own programme can only be a revolutionary democracy. Anyone who clearly understands this simple and indisputable idea will have no trouble tearing off the false epaulettes of democratism that many thoroughly corrupt liberal opportunists adorn themselves with, and in ever-greater numbers.

Any deal between absolutism and the opposition can only be reached at the expense of democracy. For absolutism, no other kind of deal would make sense. Faced with a democracy that is decisive and true to itself, absolutism has no alternative but to struggle against it to the end. But if that is the case, then democracy has no other path open to it either.

This means that a democracy that turns its back on revolution, or fosters illusions in a peaceful reformation of Russia, is in reality weakening itself, undermining its own future. Such democracy is a self-contradiction. Anti-revolutionary democracy is not a democracy.

Osvobozhdeniye, which today parades under the banner of democratism, assures us that “thanks to the decisiveness and bravery of the zemtsy, the path of peaceful constitutional reform is still open for the government. Stepping onto this path decisively and firmly would be an act of simple governmental wisdom.”

The editor and publisher of the newspaper Syn Otechestva[25] exclaims with pathos:

“As a son of my century, I do not share the superstitions of centuries past and deeply believe that the new temple to the god of freedom, truth and law will be founded here without any atoning sacrifices…

“I deeply believe that… if not today, then tomorrow we will hear the peaceful sound of a hammer hitting the first stone, and hundreds of industrious stonemasons, summoned to Petrograd, will gather here for the building of new temples.”

This is the reasoning of the many naïve ‘sons of the fatherland’ who sincerely believe themselves to be democrats. Revolution, to them, is the “superstition of past centuries”. Wearing white aprons, in a reverent mood, they begin the construction of the temple to the so-called god of freedom, truth, and law. They “believe”. They believe in the possibility of doing without “atoning sacrifices”, of keeping their white aprons unstained. They believe “in the possibility of a peaceful transition to fruitful work, because the realisation of the inevitability of fundamental changes must, at last, penetrate even the highest spheres.”

They “believe”, these spineless Petrograd ‘democrats’, and they passionately proclaim their faith until a representative of the “highest spheres”, enlightened by their propaganda, puts an end to their idealistic buzzing. But even after that they piously preserve their sole political heritage – the belief in the enlightenment of the authorities… “The path of peaceful constitutional reform, promises Osvobozhdeniye, is still open for the government. Stepping onto this path decisively and firmly would be an act of simple governmental wisdom.”

Mr Struve is trying to prove to absolutism that constitutional reform will be to its own political advantage. What conclusion can be drawn from these words? There are two options:

Maybe the “peaceful constitutional reform” that Mr Struve speaks of will force absolutism to forgo only part of its prerogatives and to strengthen its position by converting the liberal tops into supporters of a semi-constitutional throne. The only peaceful reform that would be politically beneficial to the government is one that covers up naked absolutism, which is suffering from its own nakedness, with decorations of ‘legal order’; that would convert it into a ‘Scheinkonstitutionalismus’, a ghostly constitutionalism, which would be even more dangerous to democratic progress than absolutism itself. Such a deal – the ground for which is being prepared by the spineless behaviour of the zemstvos – would certainly be in the interests of absolutism. ‘Peaceful reform’ of this sort, however, could only be achieved by betraying the political interests of the people, and, therefore, the goal of democracy. Is this the outcome that the ‘democrat’ Struve is looking for? Or is it not?

But in that case, when speaking of “an act of simple governmental wisdom”, Mr. Struve must simply be hoping to lure absolutism into a disadvantageous deal. He is attempting to ‘talk down’ the enemy; to convince the autocracy that renewal and rebirth await it after a democratic baptism; to reassure the government that there is nothing more advantageous than committing suicide for the glory of democracy; to convince the wolf that granting the gift of Habeas Corpus to the pitifully mooing democratic calves would be simply an act of zoological wisdom. What profound politics! What a genius strategy!

Either betraying the democratic mission for the sake of a pseudo-constitutional deal, or using deceitful speeches to lure absolutism onto the path of democracy.

Futile, pitiful, laughable, puny plans! Servile policy!

But our quasi-democracy will not be able to offer anything more worthwhile so long as it keeps clinging to the ghost of peaceful constitutional reform, so long as it treats revolution as a superstition of past centuries…

If it does not go further, future revolutionary development will throw it backwards; it will force it to abandon its democratic superstitions and, tailing the zemstvo liberals, to step onto the path of peaceful constitutional betrayal of elementary popular interests.

Moskovskiye Vedomosti poses the question sharply and clearly when they write that “among the Russian population there is no political party strong enough to force the government into political reforms that are a threat to its wholeness and power.” This reactionary newspaper takes the question for what it is, i.e. a question of strength. That is exactly how the democratic press, too, should look at this question. It’s time to stop seeing in absolutism a political conversation partner that can be enlightened, convinced, or, failing that, confused or deceived with words. Absolutism cannot be convinced, but it can be defeated. But for that, what one needs is not the force of logic, but the logic of force. Democracy must gather its forces, i.e. mobilise the revolutionary ranks. And this work can be done only by destroying the liberal superstitions about peaceful constitutional transformation and reassuring prospects of governmental enlightenment.

Every democrat must acknowledge, as “an act of elementary state wisdom”, that hoping for a democratic initiative from an absolutist regime – which has but a single interest: self-preservation – amounts to encouraging faith in the future of absolutism, creating an atmosphere of hesitant anticipation around it, thereby strengthening its position, and ultimately betraying the cause of freedom.

To say this clearly means, at the same time, to say something else: no agreements, no compromises, but only the solemn proclamation of the people’s will, i.e. revolution.

Russian democracy can only be revolutionary, or it ceases to be democracy at all.

It can only be revolutionary, for in our society and state there are no such official organisations from which a future democratic Russia could trace its lineage. We have, on the one hand, a monarchy, supported by a colossal, far-reaching bureaucratic apparatus, and on the other, the so-called organs of public self-governance: the zemstvos and the dumas. Liberals envision and build the future Russia based on precisely these two historical institutions. Constitutional Russia, in their view, should emerge as the legal product of a legal agreement between legal counterparts: absolutism and the duma and zemstvo representatives. Their tactic is one of compromise. They want to carry over into a new, or rather, renewed Russia the two legal traditions of Russian history – the monarchy and the zemstvo.

Our democracy is deprived of the opportunity to rely on national traditions. Democratic Russia cannot be born simply by the permission of the autocracy. However, it cannot rely on the zemstvos either, as they themselves are built not on a democratic principle, but on the basis of class and property qualifications. Democracy, if it is true to its name, if it really is the party of popular sovereignty, cannot even for a single moment allow the zemstvos the right to speak in the name of Russia. The democracy should denounce any attempt by the zemstvos and dumas to enter into an agreement with absolutism in the name of the people as the usurpation of popular sovereignty and a political masquerade.

But if not absolutism or the zemstvo gentry, then who? The people! The people, however, do not have any legal forms for expressing their sovereign will. They can only create these forms by taking the revolutionary road. The appeal for a National Constituent Assembly is a break with the entire official tradition of Russian history. By summoning the sovereign people onto the historical stage, democracy cleaves into legal Russian history with the wedge of revolution.

We have no democratic traditions, we have to create them. Only revolution is capable of this. A party of democracy must be nothing other than a party of revolution. This idea must enter social consciousness and permeate our political atmosphere; the very word ‘democracy’ must be imbued with the content of revolution, so that at a single touch it would severely burn the fingers of liberal opportunists who try to convince their friends and enemies that they have become democrats just by calling themselves that name.

‘Peaceful’ cooperation with the zemstvo or revolutionary cooperation with the masses? This is a question democracy must decide for itself – we will force it to decide, by posing this question to it not only in general terms, not only in literature, but in the most concrete form, in every vital political action.

Of course, democracy wants an alliance with the masses and strives towards it. But it is afraid of losing its influential allies and dreams of becoming the connecting link between the zemstvo and the masses.

A remarkably instructive article in Nasha Zhizn’ puts forward the idea that for a “painless” realisation of democratic reforms, “it is necessary for the intelligentsia at once, without losing precious time, to come into close contact with the broad popular masses and enter into continuous communication with them.” The article does not deny that a part of the intelligentsia strove for this earlier as well, but says that it did so by “emphasising exclusively the class contradictions existing between the popular masses and those layers of society from which the majority of the Russian intelligentsia had emerged, and continues to emerge still…” Today, a different kind of work is needed. It is necessary to awaken the “free citizen who is conscious of his rights and fearlessly defends them” in the “people”, first of all in the peasant. This work demands that “democratic intelligentsia must cooperate with the elected representatives of the zemstvo”! In other words, the so-called democratic intelligentsia must awaken free citizens not only without “emphasising exclusively” the class contradictions within the opposition, but also in “friendly cooperation” with the zemstvo opposition. This means that the intelligentsia is not only deprived of the opportunity to boldly and decisively raise the questions of agrarian reform, but it also denies itself the right to address the constitutional problem in a revolutionary and democratic way. This internally contradictory task – to awaken the masses, while trudging behind the zemtsy – cannot create a worthy political role for the democrats. In their agitation, therefore, the democrats will inevitably tell lies – not the bold, unintentional lies of the Jacobin demagogues, whose revolutionary self-sacrifice merits a share of forgiveness – but those miserly liberal lies that fearfully glance around with shifty eyes, avoid sharp questions as if afraid to step on nails, and speak in lisping, slippery language, because every ‘yes’ and every ‘no’ burns the evasive tongue. Osvobozhdenie’s proclamation about war and the constitution, which we analysed in Iskra at the time, is an example of this. This proclamation was written for the masses, strives to speak a language the masses understand, and tries to appeal to the interests of the masses.

And what does Osvobozhdenie say to the people in its proclamation? They tell the people that no one needs the war, that the Tsar didn’t want it, that the Tsar is peace-loving. They know this for a fact. They go on to say that the Tsar was misled by bad advisors who didn’t inform their sovereign about the true needs of the people, because “some dignitaries conduct state affairs not according to conscience, but to the profits they can pocket and honours they can receive, and other dignitaries are simply stupid.” To help the cause, it’s necessary to summon popular representatives. The Tsar will learn the truth from them, “as it occasionally happened in the old days, when Russian Tsars lived in Moscow.” Affairs will be managed jointly – by the sovereign, the ministers, and the assembly of popular representatives.

This is how the liberal democrats of Osvobozhdenie are building a free Russia. They take the Tsar and the whole monarchy along with him under their protection. They assign a prominent role to the Tsar in their constitution. They convene an assembly of popular representatives not to express the sovereign will of the people, but to assist the monarch. The Osvobozhdenie Party, not yet defeated in the struggle with the monarchy, not even having begun that struggle, kneels before the bearer of divine power in front of the entire Russian people.

Such is their liberalism!

Popular representatives must be situated around the throne, which is acknowledged to possess the inviolable right of historical tradition. But just what people will they represent? The people of the zemstvos and dumas – who, after all, also possess the inviolable right of historical tradition? Will the people ‘without traditions’ be represented, the people without class, property, or educational privileges? The proclamation does not give an answer to this question. It remembers that the task of the Osvobozhdenie-ists is not only to awaken the citizen in the common man, but also to remain in good agreement with the privileged citizens from the zemstvos. While appealing to the people with constitutional propaganda, the Osvobozhdenie-ists do not mention universal suffrage with a single word.

Such is their democratism!

They do not dare say: ‘down with the Crown!’ – because they do not have the courage to counterpose one principle with another, monarchy with a republic. Even before the struggle for a new Russia, they stretch out their hands for an agreement with the crowned representative of the old Russia. They base themselves on the example of the estate-based, consultative Zemskiye Sobory[26] of the past, instead of appealing for a triumphant proclamation of popular will in the future. In a word: they appeal to the anti-revolutionary tradition of Russian history, instead of creating a historical tradition of Russian revolution.

Such is their political courage!

And so, the Russian constitutional government is to consist of: the sovereign (unclear why he is needed), the ministers (unclear who they answer to) and the assembly of people’s representatives (unclear which ‘people’ they represent).

Once state power is organised on these principles, then – and here begins the central point of the Osvobozhdenie-ist vademecum [programme] – then all issues will resolve themselves, all the troubles and misfortunes of the Russian people will be lifted as if by a hand. In those countries where the people succeeded in securing a constitution, they, according to the proclamation, “everywhere established fair courts, equalised levies and eased taxes, eliminated bribery, opened schools for their children, and quickly became wealthy… And if the Russian people,” – so write the Osvobozhdenie-ists – “demanded (how?) and achieved (how?) a constitution (what kind?) from the Tsar, then they too would be saved from destitution, ruin, and all oppression, just as other peoples were saved from it… When Russia has a constitution, the people, through their representatives, will certainly abolish passports, establish good courts and administration, eliminate autocratic officials, such as the zemstvo chiefs, and in local affairs will be governed by their own freely elected people, will establish a multitude of schools so that everyone will be able to receive higher education, be freed from all constraint, corporal punishment (after receiving ‘higher education’?), and live in prosperity. In short, with a constitution, meaning the country being governed by the Tsar (how about without the Tsar?) together with an assembly of popular representatives, the people will be free and will achieve a genuine, good life.”

So write the ‘democrats’ who condemn “exclusive emphasis on class contradictions”!