In 1968, revolution broke out across Pakistan, overthrowing Ayub Khan’s hated military dictatorship. The national oppression of Bengalis within East Pakistan had produced a revolution along class lines. However, due to the failures of its leadership, the revolution was transformed into a bloody civil war, ending in the secession of East Pakistan into modern Bangladesh.

The Bengali people fought like tigers to win national self-determination. Nobody knows exactly how many people died during the War of Independence, however estimates range from 300,000 to 3 million!

This period produced many martyrs for the revolutionary cause, but one thing that is rarely spoken about is the instrumental role played by women.

Women’s oppression

Something that is very well documented, however, is the barbaric treatment of women by the Pakistani regime during the war.

In her book Women, War and the Making of Bangladesh, Yasmin Saikia describes how:

‘‘Women were attacked in their homes, stripped naked in front of their family members, raped and thrown into drains. They were imprisoned in sex camps… their hair was chopped off, they were tied down and repeatedly raped, forced to take off their saris and wear rags or mens shirts, denied the food they were accustomed to, and many starved and died.”

Saikia interviewed a number of women who detailed harrowing accounts of their treatment. One woman, under the pseudonym Nur Begum, explains how her husband, who was a Bengali freedom fighter in the Mukti Bahini (Liberation Army), was brutally murdered in front of her eyes. She was then repeatedly raped:

“The Pakistani army kept me naked. I was unconscious when it happened… they had tied me to a chair… One after another they tortured me. I could not speak. My lips were swollen, my face was puffed up and my entire body had bite marks. They cut my arms with blades because I was shouting… I was tortured until independence… I saw two dead girls, they tortured even their dead bodies; they were dead already.

“The Pakistanis came in group after group. They did it in front of everyone… The girls ranged in age from 14 to 22 years… The soldiers cut the girls’ hair short so that they could not strangle themselves using their hair. Their arms were smashed, so they could not raise their arms… Because my husband was a freedom fighter, I was tortured relentlessly. They used to say mukti, mukti. My arms and legs were smashed.”

Again, nobody knows exactly how many women were abused, but estimates are in the tens, even hundreds, of thousands. Dr Syed Ahmaed Nurjahan, a doctor who volunteered at women’s clinics at the time, recounts carrying out 200 abortions in one day from women carrying the children of their rapists.

During the War of Independence, Pakistani soldiers were “ordered by their superiors to teach Bengalis a lesson”. Methods of sexual abuse and rape were used systematically to deter Bengalis from entering the struggle and to dishonor and humiliate the men. This was particularly zealously carried out by the fanatical Islamic fundamentalist paramilitary groups (Al-Badr and Al-Shams) associated with the Jamaat-I-Islami party.

It is no surprise that these brutal methods were rolled out at this time. Attitudes towards women on the subcontinent were (and still are) extremely backwards. However, these aren’t ideas innate to men in general, but, as Engels points out in his book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, they are a product of class society and the ownership of private property.

Women were regarded as property to be traded between families in order to pass down private property to male heirs. For example, there were many instances of child marriage and wealthy families forcing women to practice purdah: strict and oppressive segregation from males.

The particularly acute nature of women’s oppression on the subcontinent was massively exacerbated by the cynical actions of British imperialism, particularly during the partition of India and its aftermath.

In 1946, the masses rose up in a revolution against the British occupation of India. This was one of the most inspiring events in history, as men and women, Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs joined arm in arm in a joint struggle for a dignified existence.

The revolution threatened the property of not only the British, but also of the wealthy Hindu and Muslim ruling classes. Britain could no longer maintain direct domination, so had to resort to divide and rule tactics. In collaboration with the Hindu and Muslim ruling elites, the subcontinent was divided down religious and sectarian lines.

Approximately 2 million people were killed, 10-20 million were displaced and 75,000 women were abducted and raped in the frenzy of communal violence unleashed by the partition of India.

As a recent study into violence against women during the partition explains, “Among the sufferers, the ones who were impacted the most were the Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh women. After all, it was the women from both sides of the border who were separated from their families by the men of the other communities, gang-raped, and mutilated with ‘Hindustan/Pakistan Zindabad!’ (translated into ‘Long Live India/Pakistan!’) tattooed on their bodies.”

Another study reports that, “[T]here are accounts of innumerable rapes… of women being stripped naked and paraded down streets, of their breasts being cut off, of their bodies being carved with religious symbols of the other community…”

The two states of India and Pakistan were born out of the most obscene levels of violence, which left deep, lasting scars on the fabric of both societies.

Both the Hindu and Muslim ruling classes jealously guarded their wealth after partition by continuing to divide and rule down religious and ethnic lines, leading to multiple wars and campaigns of ethnic cleansing. Women inevitably bore the brunt of these.

Pakistan, for example, was an artificial state composed of many, mainly Muslim, ethnic groups (including Bengalis), who were hyper-exploited by a small clique of twenty-two Punjabi capitalist families.

On a capitalist basis, the only way to stop the country from tearing itself apart was by uniting Muslims to incite violence against Hindus and Indians (the same methods were likewise used by the Indian ruling class against Muslims and Pakistanis), thus provoking communal violence. This method was, and still is, used by the ruling classes of the subcontinent and becomes more acute at the outbreak of a crisis.

For example, internal social and political pressures within Pakistan during the 1960s led military dictator Ayub Khan to launch a military adventure in Kashmir, declaring war on India, which occupied most of the territory, in 1965. To engineer support for this war, there was a concerted, rabid anti-Hindu propaganda campaign.

The heightened atmosphere whipped up by the Indian and Pakistani ruling classes expressed itself in numerous tit for tat killings and pogroms. The worst of these were the East Pakistan communal riots in 1964/65 where thousands of Hindus were rounded up, murdered, tortured and raped.

This same tried and tested method was used again after the 1968 revolution and during the Bangladesh War of Independence. The ruling class of West Pakistan could never allow Bangladesh independence, as it would mean losing their right to exploit them as a colony. Therefore, during their brutal invasion, they encouraged the most vile methods by which to put down the aspirations of the Bengali masses.

The Bihari community (Urdu speakers living in East Pakistan) and ultra-conservative Islamic fundamentalists were whipped up into a frenzy by the Pakistani ruling class and told to treat Bengalis like they would Hindus. The inevitable result of this can be read in the harrowing first-hand accounts detailed above.

The capitalist class of the subcontinent are particularly vicious. Their wealth and power rests upon the hyper-exploitation of almost one quarter of the world’s population. Wages are very low, especially for women, and working conditions are particularly horrific. The capitalist system and women’s oppression are therefore inextricably linked.

No ruling class has ever given up their power and privileges without a fight. The Bangladeshi War of Independence clearly shows the lengths that they will go to in order to defend their interests.

It is no surprise, then, that throughout history, women have often been the most determined and self-sacrificing layers in revolutions. This was no different during the Bangladesh War of Independence!

The role of women during the war and revolution

Despite the threat of suffering a fate worse than death, thousands of women joined the liberation struggle. They played an instrumental role in spying, secretly transporting supplies, nursing the wounded, converting their homes into makeshift hospitals and in some cases even fighting in the war itself.

Shirin Banu Mitil, an activist in the Communist Party who participated in the revolution and war, explained:

“Women fought in different ways away from the forefront in the liberation war. They somehow, almost miraculously, tore down trees and lay them down on streets, barricading the Pakistani soldiers from moving forward. To Bengali freedom fighters, they provided rice, shelter and information. Every house was a camp against the Pakistani Army.”

Royeka Begum, who was pregnant at the time, would shelter and feed freedom fighter battalions. She would meet them in the dark of night with food. She kept weapons in a well by her house, knowing what would happen to her if she were caught.

She said: “People used to say a lot of things… that she goes out alone at night… chats with the Muktis, feeds them… I told my husband all this. He said, ‘Let them talk. It’ll stay on people’s lips only. You have to do what you must do.’”

Laila Ahmed was a medical student who, after her father was shot by the West Pakistani army, sold all of her belongings and walked hundreds of miles – developing an abscess and kidney infection in the process – to join the Gobra training camp in Kolkata, a special women’s training camp organising 234 female fighters.

Here they trained in first aid, espionage, weapons training and nursing. She recounts her experience:

“They (the women) were given white saris each, our bedclothes and a mattress. All of us in the camp had taken an oath not to use a pillow as long as our country was not free… When we were not in class or training, we spent our time singing war songs…

“Generally, I got tetanus injections, vitamins, ointments and creams for injuries and pain, medicine for infection, and so on. We used to join protest rallies against international and national policies that were not in favour of Bangladesh. We also used to give public speeches on what was happening in East Pakistan and about the suffering of our people.”

The women there were not simply engaged in practical tasks, but were inspired by revolutionary politics. Laila cites the oppression of women as one of the key reasons for joining the political struggle and explains:

“Most of the girls who were in this camp were actively involved in politics during their student days, before 1971… because they wanted to do something for the country.

“They used to tell us the history of war and fighting on the borders, and about Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

“You will find it hard to imagine the obstacles we fought then. It was a very different world. But we persisted, and the women who came to work with us were breaking many rules and taking risks to assist us. There was a revolt, you can say, by women and it had a great impact. You cannot understand it now. The liberation war had made this possible.”

During the revolution, they had a taste of what life could be like. Alamtaj Begum Chhobi, a left-wing student activist, says:

“When the liberation war began, Bengalis formed a togetherness for one cause that had never existed before or will ever exist again. There was no difference between male and female. We often slept side by side across the floor, but at no point were we ever disrespected.”

These are just a handful of examples of the thousands of brave women who made victory in the War of Independence possible. The revolution awakened something deep inside of all of them – a sense of their own self-worth and power as active participants in history. They refused to be slaves anymore, and they would sacrifice everything if they had to. Women had the least to lose and the most to gain – this explains the sacrifices women made during this period, and every revolutionary period, for that matter.

Such is the power of a revolution: even the most entrenched backwards and reactionary ideas are cast aside once the previously divided masses enter the scene of history and take fate into their own hands. Through the course of struggle, they recognise that they are stronger when united against their common enemy.

Post-independence

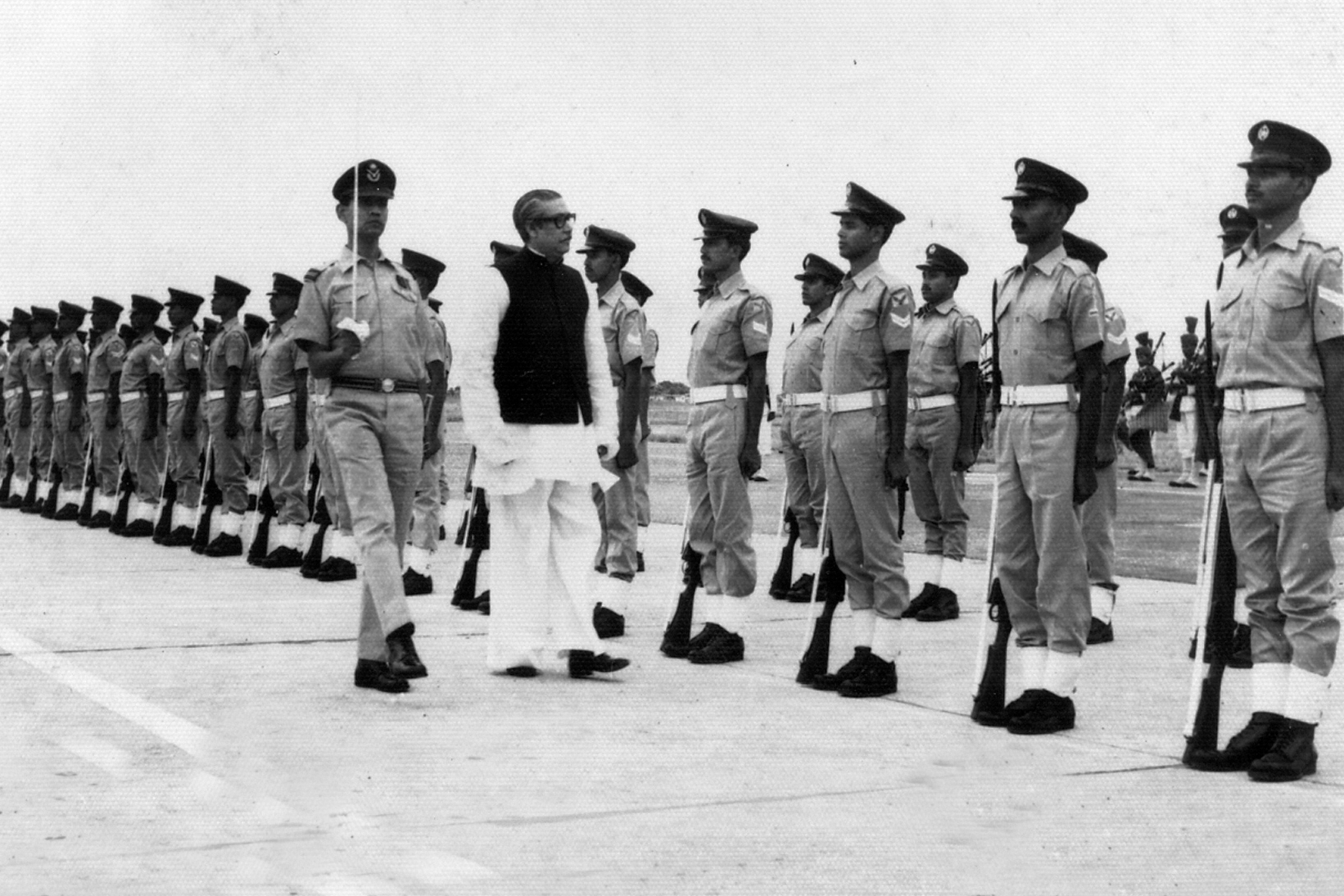

After the war ended, a new government was formed in newly independent Bangladesh by the Awami League, led by Mujib-ur-Rahman. A period of counter-revolution ensued. The new Mujib-led government initiated a campaign of terror, murdering and imprisoning thousands of left-wing activists.

Mumtaz Begum was a courageous revolutionary student activist who gave enormous sacrifices during the war. After being turned away from male camps, she raised funding to form her own female freedom fighter camp. They were chased down relentlessly by both Indian and Pakistani authorities, but as the war ended, she recounts their persecution by the new Bangladeshi regime:

“We were doing socialist work, but we were keeping it secret. Our condition was like ‘na ghar ka aur na ghat ka’ (Hindustani phrase for suddenly finding themselves on the wrong side of the political fence).”

Despite the enormous self-sacrifice for the cause of independence, women were once again relegated to second-class citizens. Leila Ahmed, who was mentioned previously, stated: “There are many more people who have really sacrificed for this country, but they have not benefited from the politics after liberation.”

After independence in 1971, Mujib’s government created the ‘Birangona’ programme to compensate the countless women who were abused during the war. However, rather than receiving any compensation, women who came forward were then ostracised from society, shunned by their families and left to fend for themselves.

The government gave out incentives to men, such as state jobs, to marry these women. Many men did so, only to divorce the women after they had received their job.

One women told the story of how she was raped at the age of 12 and became pregnant. She underwent a forced state abortion at seven months pregnant. Her father and uncle became ill because of what happened to her and died soon after.

“People in our village knew about the incident and they passed obscene remarks and gossiped about me.”

She was given no money under the Birangona programme. She was extremely poor with no savings and forced to work for poverty wages in brutal conditions.

“My life was ruined for no reason… I want to live with others who are nice and can help us grow and progress. I also want to have some money and earn a nice living. Is that too much to ask?”

The most tragic example was of Nur Begum, mentioned towards the beginning of the article, who was gang raped by members of the Pakistani Army. In an interview with Yasmina Saika, she details the way she was ostracised by society and abandoned by the new Bangladeshi state even after coming forward for the Birangona programme:

“My name is not included in any gazette. I don’t have any record. All my documents have been destroyed. A fake freedom fighter promised to marry me, to create a family with me. They got us married and he was given a government job, which he continues to enjoy. He is living happily with his wife and children, but I couldn’t enjoy the same benefits or have children with him. My child has suffered. Tell me what kind of a country is this? People laugh at me, they jeer at me. Where can I get peace? It would have been better if I had died then. It is fruitless to live in this Bangladesh. Has it produced a result for people like us?… To fight for our freedom, to protect our country, I became a Birangona.”

The revolutionary period of 1968-75 and the War of Independence did not end in the abolition of class society and the building of socialism, the precondition for true women’s emancipation. Instead, it produced the conditions for the enrichment of a new up-and-coming Bengali capitalist class and wealthy state bureaucrats who were completely subordinate to the interests of imperialism.

There was no appetite among these wealthy elites to continue the class struggle and extend democratic rights to women. At the end of the day, they had achieved their narrow interests from the independence struggle and demanded a return to stability and order.

Despite the revolution being overtly secular in character, the period after 1975 was characterised by multiple military dictatorships using the question of religion to divide and rule.

A strict Islamic constitution was drafted, which severely curtailed the rights of women. The fundamentalist paramilitaries responsible for most of the atrocities during the war were rehabilitated, emboldened and given free rein to terrorise the population.

Marx explained this phenomena when he said that: “when want is generalised, all the old crap is revived”, i.e. as long as exploitation and inequality exist, where a minority of wealthy individuals profit from the poverty of the majority, this ruling class will promote the most backward and divisive ideas to maintain their privileged position.

Women and the class struggle

Women had tasted freedom, and they wouldn’t stop until they got it. This led many of them to revolutionary conclusions. The ruling class of Bangladesh have therefore tried every method to stop women from thinking for themselves.

The documentary Their War attempts to highlight the role of women during the war, showing interviews with female participants and victims. During the film, one of the film-makers comments that: “the well-off have built a wall of wealth, they’ve kept ‘71 at a distance… I’ve heard from my grandparents that the way the poor helped the rich in ‘71, the rich didn’t help the poor… the war of the rich and that of the poor are actually different wars, and the war of the prosperous women and that of poor women are also different.” This is absolutely correct.

Furthermore, Suhasini Devi, a social worker and activist during and after the war, said:

“People sacrificed so much then, but we are not really enjoying independence now, particularly not the women who were victims of the war for freedom; they got nothing… It is an irony: today our country is ruled by a woman, and she doesn’t treat her children equally… One can change the administration, but that is not enough for real change to take place.”

Wealthy women, like the recently deposed tyrant Sheikh Hasina, were able to use their wealth and family connections to rise to power. Hasina, the daughter of Mujib-ur-Rahman, piggybacked off the sacrifices of countless brave women, who gave their lives so that she could sit at the top of a state that degrades millions of women and condemns them to a life of servitude, poverty and misery.

In 2021, the Bangladesh Women’s Lawyers’ Association reported that “84 percent of women face sexual harassment in workplaces and public spaces, such as in schools, on the streets, and in public transportation, and even at home. Many more women face sexual harassment online.” Clearly, having a female prime minister did nothing to solve the real issues facing women.

Ultimately, Bangladesh is a capitalist society which bases itself upon providing cheap garments for enormous foreign multinational corporations. 80 percent of workers in the garment industry are women. They receive only £80 per month and work in horrendous conditions – Bangladesh is in the top 10 nations in terms of restrictive labour laws. Many workers report horrifying treatment, including being slapped and beaten for failing to reach absurd output targets.

It was this system that made Hasina obscenely wealthy. That is why she was more than happy to send in the police to kill and maim women who dared to protest these conditions.

The garment industry accounts for 11 percent of the GDP of Bangladesh and over 80 percent of export earnings. Essentially, 3.2 million women have the power to grind the economy to a halt! The power of the working class and particularly of working class women was seen in the revolution that took place in Bangladesh last summer. The threat by garment workers to carry out a mass strike was a factor, along with the massive entry of the masses onto the scene, that sealed the fate of Hasina’s regime.

Despite countless examples of the heroic struggles and enormous sacrifices of women, women’s oppression still exists and in many places is getting worse. The global crisis of capitalism is squeezing working-class women to breaking point.

The horrifying accounts of women’s oppression during Bangladesh’s War of Independence make up only a small part of the innumerable casualties suffered in the class war.

Our task is not to lament, but to avenge their deaths and mistreatment by finishing what many of these brave women started: the revolution to overthrow capitalism and the building of a socialist society, which will be the precondition for the true emancipation of women.

Therefore, it is true now more than ever that a woman’s place is not in the home, or the kitchen, or behind a husband. A woman’s place in the revolution and the Revolutionary Communist International!