What can the labour movement do to help thwart the Israeli war machine?

Over the last two years, many Canadian unions have penned statements condemning Israel’s actions in Gaza. But as Israel continues their genocidal campaign, many feel that more must be done.

Union officials claim that they can’t do much this far from Palestine. But is this true?

A look at Canadian history shows key moments where workers withdrew their labour in order to thwart the actions of a foreign regime—and with meaningful results.

July 3, 1979 in Saint John New Brunswick was one such moment. On that day, Saint John’s dockworkers, backed by unions around the country, carried out an illegal strike that halted the transport of nuclear materials to the then military regime in Argentina. This event, described by one publication as “the single most dramatic example of Canadian trade union solidarity with workers in the Third World,” deserves to be studied as a positive example of workers using their power in the service of international solidarity.

Dirty business

In 1976 the Argentinian military overthrew the government of Isabel Perón in a U.S.-backed coup. A campaign of terror followed. Death squads eliminated trade unionists, socialists, and anyone seen as hostile to the new regime and the U.S.-friendly business elites. Anywhere from 20,000-30,000 people were murdered or “disappeared” over the course of what was later dubbed the “Dirty War”.

While raising the occasional “concern”, these atrocities meant little to the Canadian government. They had already sold Argentina a CANDU nuclear reactor in 1973, despite widespread suspicions that they were developing a nuclear weapons program. At that point, the Argentinian military was already powerful and known for egregious human rights abuses. Atomic Energy of Canada Limited (AECL) chief Ross Campbell defended the deal by saying that “business is business and human rights are human rights.”

The Canadian government continued this approach in the late 1970s and they sent a team to explore the sale of a second CANDU reactor.

‘No CANDU for Argentina’

The decision sparked outrage. To stop the sale of nuclear materials Argentinian expats, trade unionists, and other activists formed the “No CANDU for Argentina Committee” (NCAC). They were supported by the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), the Ontario Federation of Labour (OFL), the United Auto Workers (UAW) and the United Electrical Workers (UE).

In September 1978, the NCAC discovered that a major component for Argentina’s existing CANDU reactor would be shipped out from Saint John the following year.

In response, the NCAC approached Canada’s department of external affairs with their objections. Not wanting to jeopardize their business relationship with Argentina, the Canadian government refused to budge.

The NCAC would have to take matters into their own hands.

They reached out to Saint John and District Labour Council President Larry Hanley, who invited them to speak at a council meeting. During that meeting, NCAC member and Argentinian expatriate Enrique Tabak told the assembled workers about the horrors being committed in Argentina, the persecution of trade unionists, and the complicity of the Canadian government. He received a standing ovation and a commitment of support to halt the shipment.

The Saint John Labour Council released a statement denouncing the shipment and the Canadian government’s support “for a repressive military junta.” It also asked that Saint John dockworkers cooperate with the NCAC. It was these workers, members of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) Local 273, who were to load the cargo bound for Argentina.

The Labour Council’s support went beyond issuing statements. Its members actively investigated the scheduled movements and contents of cargo out of the port of Saint John, and supplied that information to the NCAC and supportive unions. The OFL distributed literature to its members and requested telegrams in support of the coming action.

The power of the workers

By mid-1979, the NCAC had learned the contents and date of the shipment. The contents: $45-million worth (in 1979 money) of heavy water, essential to operating nuclear reactors. The date: July 3, 1979.

The NCAC decided to form an information picket outside of the port and hold up the shipment. Their goal was to show the Canadian government that dealing with Argentina’s regime would be costly, and to inspire other workers to take similar actions.

In the leadup, NCAC activists spoke at trade union meetings across Canada, gathering support. By July 3, NCAC had the backing of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour (NFL), the Marine Workers Federation (MFW), the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway, Transport and General Workers, and many other organizations.

The message to Saint John’s dockworkers was clear: the labour movement has your back.

But statements, while important, remain just pieces of paper. Ultimately, the shipment could only be blocked out by the dockers themselves. Not a wheel turns, not a light bulb shines, not a shipment sets sail, without the kind permission of the working class.

As soon as the NCAC’s plans became public, the dock workers faced enormous pressure to take no part in them. Newspapers ran stories saying that refusal to load cargo would constitute an “illegal strike,” and raised the threat of fines, disciplinary measures, and a loss of pay.

In the face of this pressure, the leaders of ILA Local 273 buckled. The union’s business agent openly opposed a work refusal, while the secretary of the union lamented that they had “no choice but to honor our collective agreement.” Despite the fact that the NCAC reached out to the local early on, the evidence suggests that the leadership refused to communicate with their members about the plans and objectives for July 3.

Instead, it was a rank-and-file docker, Jimmy Orr, who helped convince his fellow workers of the importance of international solidarity and the need to refuse work on July 3. He described the feeling of him and his peers leading up to the day:

“We had a few dissenters but they were a distinct minority. The great majority of the [union] local was behind it, you know, they understood the situation.”

If not for the crucial efforts of workers like Orr inside the local, the entire action may have amounted to nothing.

‘No Hot Cargo’

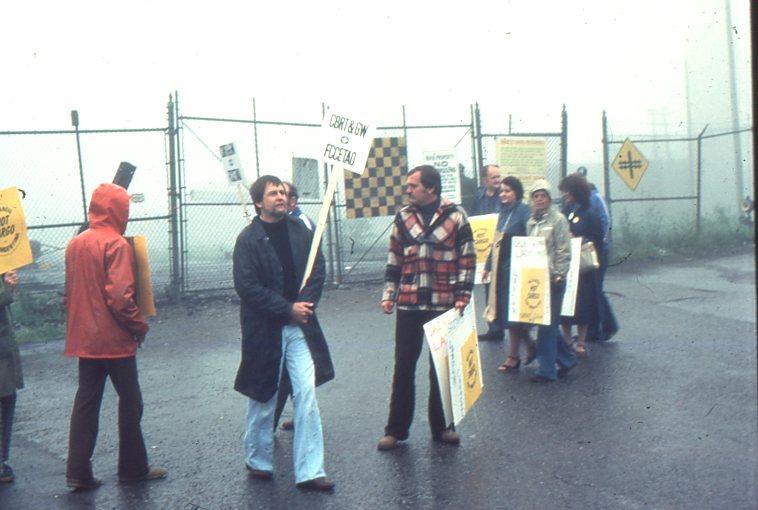

In the early morning of July 3, NCAC assembled a picket line outside the port of Saint John. They came bearing bright yellow “Hot Cargo” buttons and literature about the junta in Argentina. They also came with additional demands—the release of 17 political prisoners, most of them trade unionists, languishing in Argentina’s jails.

Not long after, the first batch of dock workers showed up at the port for work. NCAC activists immediately approached them to explain their action and the repression of trade unionists in Argentina. Labour Council President Larry Hanely implored his fellow unionists not to cross the line.

Incredibly, despite the orders of their local union leaders, despite the threat of fines and loss of pay—the workers refused to cross. They took “Hot Cargo” pins to wear, and stickers to label the cargo itself.

The dockworkers came to view the fight of workers in Argentina as their own—in part due to the efforts of the NCAC. The persecution of trade unionists in Argentina was an attack on trade unionists everywhere. This was international working class solidarity in action.

The actions of the Local 273 rank-and-file inspired the few remaining workers at the port, also union members, to join them on strike. The port of Saint John was totally shut down for a 12-hour period.

While this was a short lived action, it represented a huge step forward. Instead of limiting themselves to appeals to politicians, workers had taken concrete action themselves.

This also set a precedent—it was one of the few acts of international solidarity involving an illegal work refusal in Canadian history at that time.

Fruits of victory

In the course of events on July 3, NCAC received a flurry of supportive telegrams from other unions expressing their desire to take action themselves. This included Vancouver dock workers, who promised to refuse loading any hot cargo destined for Argentina. The example had been set.

A mood of panic spread in Ottawa and Buenos Aires. Canada’s Minister of External Affairs, having first ignored the NCAC, pledged to raise their concerns with the Argentine regime. On July 5, just two days after the strike, word was received that one of the 17 political prisoners had received a visa to come to Canada. On July 13, further word was received that 11 more of the prisoners had been freed, with an additional three being released but sent into exile. The strike had delivered results.

This small event shows the immense power that the working class holds in its hands. How many times have workers placed demands on the government, only to be ignored? The fact of the matter is that the Canadian government and the wider ruling class feared that the example of the Saint John dockworkers would spread. With labour militancy on the rise all throughout the 1970s, the last thing they needed was port workers stopping shipments.

The example set in Saint John also established a tradition. In 1982, another hot cargo edict was issued to prevent a further shipment of nuclear fuel to Argentina. On this occasion, the presidents of both Local 273 and the NFL made it known that they were prepared to go to jail before handling the cargo.

In 2003, Local 273 issued another edict against any shipments destined for Iraq in protest of the U.S. invasion. In 2018, Saint John dock workers once again faced an information picket aiming to prevent the transport of military vehicles to Saudi Arabia—and once more, they refused to cross.

Most recently, in June of 2025, the NFL issued a hot cargo edict against military hardware destined for Israel, in protest of the ongoing genocide. In New Brunswick, the legacy of 1979 lives on.