In the definition of chameleon in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, we find, among several characteristics, its “unusual ability to change the colour of the skin”. We also find synonyms for chameleon, such as “opportunist” and “weathercock” – “a person or thing that changes readily or often”, and “a person who often changes their beliefs or behaviour in order to please others or to succeed.”

Now, you may ask, what does this have to do with reformists? Well, if we look more closely at reformists in the labour movement, we see how they can easily swing both to the left and the right – in effect changing their political colouring – as the environment they are working in changes, and as they come under pressure either from the working class or the ruling class. In that sense, a comparison with chameleons is justified, and the term ‘political chameleon’ fully fits as a description of the reformist.

Chameleons can change their colour and their skin patterning to send out different signals, but the characteristic we are interested in here is their ability to blend into their surroundings – i.e. change colour as the colour around them changes – so as to remain hidden from a potential predator.

When reformists change their colour, however, it is for a different reason. They manoeuvre – sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously – tacking to the left, even far left when the pressure is very high, or to the right, but in a way which is designed to avoid open class confrontation.

And when they are in a position to actually have a real impact on the class struggle, when they could give the necessary lead that could massively raise the confidence and the consciousness of the working class, they retreat and seek compromises of some kind with the right-wing reformists, thus serving the interests of the class enemy, which has always ended throughout history in defeats for the working class.

The fundamental characteristics of reformists, their total lack of a dialectical understanding of how capitalism works, together with their lack of confidence in the ability of the working class to mobilise in a revolutionary direction, is what gives them chameleon-like characteristics.

They are very easily influenced when capitalism goes through long periods of upswing. This makes them incapable of seeing beyond the immediate conditions they are working in, and this applies both when the system is going through periods of strong economic growth and when it enters into crisis. As Trotsky pointed out in the introduction to his classic, The Revolution Betrayed: “Whoever worships the accomplished fact is incapable of preparing the future.”

And the reformist is an empiricist who proudly sticks to the so-called ‘facts’, and is incapable of seeing the overall, long-term historical process within which those facts appear. They belittle genuine Marxism, claiming that it doesn’t have the answers to the problems faced by the workers today. They claim to be pragmatists and have no time for the ‘theorising’ of the Marxists. Their lack of theoretical understanding, however, means that when capitalism is booming, they are incapable of seeing the inevitable crises of the future, and therefore are incapable of preparing for them.

The material basis for reformism and its rejection of the need for revolution was to be found in the period of capitalist upswing towards the end of the 19th century. In those conditions, to the superficial observer, it seemed that capitalism had solved its internal contradictions, and that therefore Marx required revising. And according to this thinking, Marxism was not able to offer an explanation of the prolonged upswing.

In the United States we had the so-called ‘Gilded Age’, which saw high levels of economic growth that lasted from the late 1870s until the early 1900s. In the same period Germany emerged as a major industrial power in Europe. And Britain, although it was feeling the pressure of US and German competition, also experienced a boom – after a previous slowdown – from 1895 until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

It was in this period that we witnessed the degeneration of the social democracy, of the parties that were part of the Second International, most of whom had originally been founded on the basis of the ideas of Marxism. Initially, its leaders continued to pay lip service to revolution, even voting for revolutionary-sounding resolutions, while in practice collaborating with the capitalist class. But eventually, they even abandoned lip service, and openly stated that capitalism could be reformed and revolution was no longer possible or even necessary.

The First World War was to rudely interrupt the reformists and confirm that all the contradictions within the system, brilliantly explained by Marx, had not been eliminated. Now there was a deep crisis of the system, which opened up an epoch of revolution and counter-revolution, with October 1917 in Russia being the clearest evidence of the revolutionary potential that the crisis of the system had unleashed.

The openly treacherous role played by the now reformist leaders of the mass workers’ organisations, however, meant that the enormous revolutionary potential was squandered in one country after another, in Germany, in Italy, in France, Hungary and many more, and this in turn prepared the conditions for the rise of fascism and the Second World War.

The end of the Second World War saw, yet again, revolutionary potential – see Italy, France, Greece and many others – but it was once again lost due to the reformist outlook of the leaderships of the mass workers’ parties in that period, this time both the Social-Democratic and Stalinised Communist Parties. This led to the defeats of many movements, and the receding of the class struggle, which in turn prepared the political conditions for the immense economic development of the postwar boom.

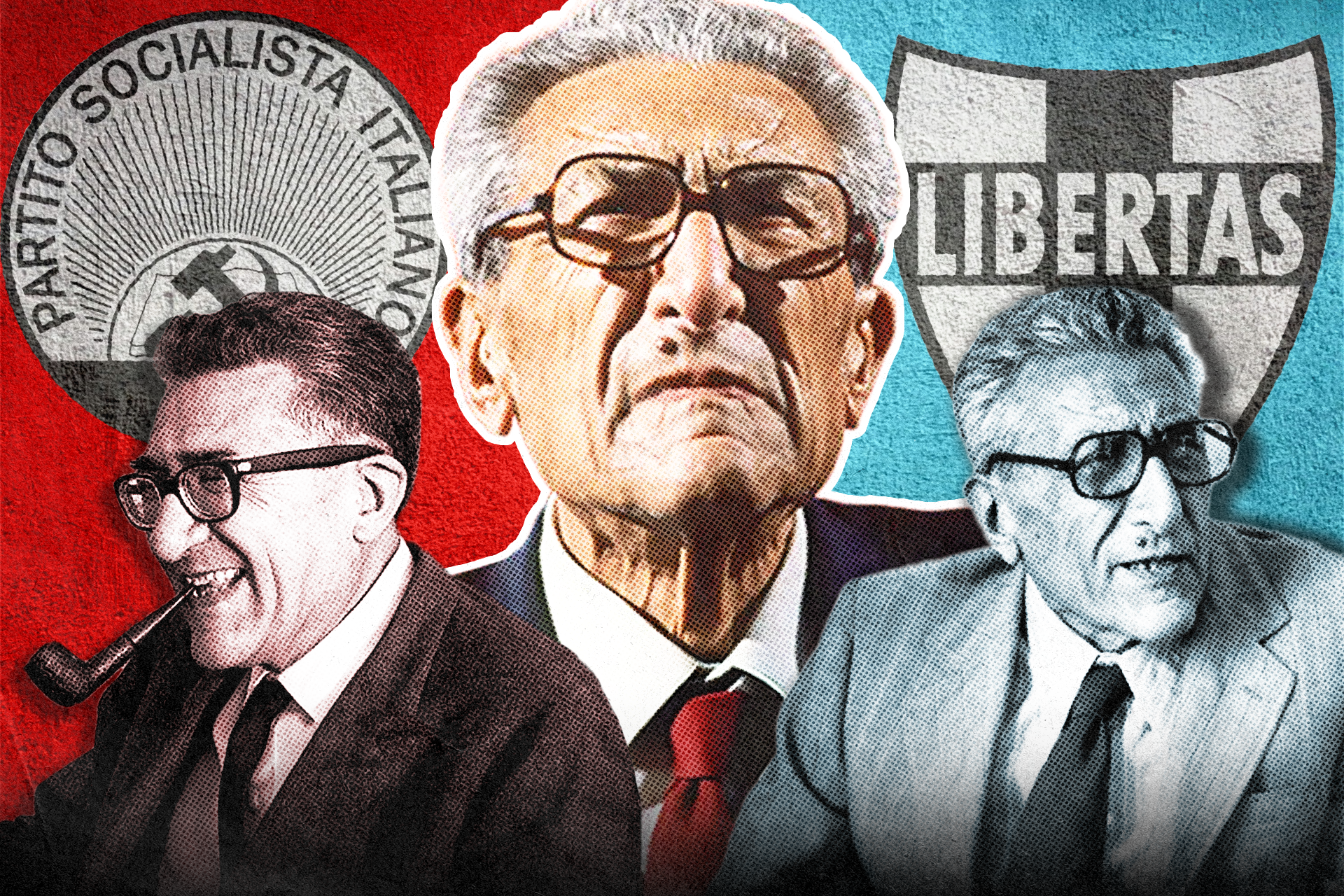

Riccardo Lombardi

This was the material basis for the further degeneration of the traditional mass organisations. And this is where my story of one particular political chameleon begins, that of Riccardo Lombardi, who is remembered in Italy as the leader of the left wing of the PSI – Partito Socialista Italiano – in the 1970s. But before elaborating on his chameleon-like characteristics, it is worth giving a bit of historical background to the man. Who was Riccardo Lombardi?

He was born in 1901 in Sicily, and moved to Milan when he was 18 to study engineering. His political activity started in 1922 when he joined the Italian Popular Party (Partito Popolare Italiano, PPI), adhering to the ‘left’ of that party. It is worth noting that the PPI was in effect the precursor of what would emerge as the Christian Democracy, the conservative party of the bourgeoisie, at the end of the Second World War. He very soon broke with that party and moved to the left, taking an interest in Marxism.

He read the Communist Manifesto and The Class Struggles in France, as well as volumes one and two of Capital. But he also admitted that his understanding of Marx was influenced by Benedetto Croce’s criticisms of historical materialism. Croce was a bourgeois liberal and philosophically an idealist. So right from the beginning we see Lombardi’s inability to grasp the true essence of Marxism, and this would determine his political thinking for the rest of his life.

He participated in some actions of the Arditi del Popolo, the anti-fascist group founded in 1921, that tried to forcefully oppose the rise of fascism, and he later collaborated with both the Communist Party’s underground organisation and the liberal antifascists once the Mussolini dictatorship had been consolidated.

In August 1930, after participating in the activities of a group distributing leaflets to factory workers in Milan, he was arrested by the fascist militia and subjected to beatings that caused a permanent injury to one of his lungs, which would give him health problems for the rest of his life. He was subsequently placed under surveillance by the fascist regime.

He was therefore a courageous and determined anti-fascist, and no one can take this away from him. It also gave him authority within the Italian left as a whole. However, his adherence to Marxist thinking was to be superficial and short-lived. He continued to quote Marx, but he was also influenced by the ideas of Keynes and Schumpeter, and the ‘mixed economy’ theories. All this led him to what many defined as his ‘liberal socialism’. This meant that he did not envisage an end to capitalism, but simply a reworking of the system, with some ‘progressive’ reforms.

This explains why in 1942 he was one of the founders of the Action Party (Partito d’Azione), a party that was fundamentally a left/liberal formation that rejected Marxism and the class struggle. As a leading representative of the Action Party, he was also a member of the National Liberation Committee of Northern Italy (CLNAI). He would then go on to become Minister of Transport in the coalition government (December 1945 to July 1946), which saw the open collaboration between both the Communist Party and the Socialist Party with the Christian Democracy.

The Action Party won only 1.45 percent of the votes and seven seats in the 1946 Constituent Assembly elections, and collapsed in 1947, with its leading figures moving in different directions, some joining the PSI (Socialist Party), while some joined the Republican Party, an openly bourgeois formation. Lombardi decided to join the PSI which he would represent in parliament until 1983, a year before his death.

In the period 1956-64 Lombardi was at the head of the PSI’s economic commission, and his position is summed up in a speech he gave in parliament where he explained that the party set out to “operate within capitalist society to change its balance of power and income in favour of the working classes” (Discorsi parlamentari, by M. Baccianini, Rome 2001). Thus, his position remained a classical reformist one of working within the confines of capitalism while attempting to introduce reforms favourable to the working class.

The impact of the postwar boom

This illusion that one can reform capitalism was to be enormously strengthened by the economic boom taking off in that period. World capitalism was about to go through an unprecedented period of expansion. France between 1947 and 1973 saw 5 percent growth per year on average. West Germany saw prolonged economic growth in the same period, with industrial production doubling from 1950 to 1957, and gross national product growing at a rate of 9-10 percent per year. Japan saw annual growth rates of around 10 percent for a sustained period.

The Italian economy, in this context, went through very rapid expansion, seeing record high growth rates of 5.8 percent per year between 1951 and 1963. Productivity in industry grew by an average of 8 percent per year in the decade 1953-63 – higher than China’s rate of productivity growth today! Investments were growing at around 10 percent per year and profitability was also shooting upwards.

One has to remember that Italy emerged devastated from the Second World War. In 1947 inflation had reached 30 percent, the value of the lira had collapsed and exports were falling. As Augusto Graziani in his L’economia italiana dal 1945 a oggi (published in Bologna in 1972) pointed out:

“In the immediate postwar period, few could have predicted the remarkable capacity for expansion that Italian industry would reveal over the following decade. Above all, few believed that Italian industrial development would rely on sectors (such as steel, chemicals, and automobiles) that seemed particularly difficult to expand…”

The period of the so-called ‘Italian economic miracle’ of 1956-63 created hundreds of thousands of new jobs – by 1963 there were 5.4 million industrial workers. Together with rapid growth in the average per capita income, high levels of accumulation of capital, industrial development combined with growing levels of exports and monetary stability, these conditions inevitably were going to impact the consciousness of both the mass of working people and the reformist leaders of the labour movement. And we will see this in a speech that Lombardi gave at the 1963 national congress of the PSI, which we will quote later.

Throughout the 1950s the Christian Democracy benefitted from the betrayal of the revolutionary potential of the period 1943-48. Due to their class collaboration, both the Communist Party (PCI) and the Socialist Party (PSI) suffered a significant electoral setback in the 1948 elections, and this is what allowed the Christian Democracy to hold on to a strong parliamentary position, consistently winning more than 40 percent of the vote throughout the 1950s. This meant that it could govern with the help of a number of small bourgeois parties, such as the Republicans and the Liberals.

However, by the early 1960s this started to change, and in the 1963 elections the Christian Democracy’s share of the vote went down to 38 percent, and it won only 260 MPs in the 630-strong parliament.

This weakening of the Christian Democracy required a widening of the coalition in parliament if it was to continue governing the country. In 1960 they had sought parliamentary support from the MSI (the Italian Social Movement, which was set up in 1946 by elements from within the old fascist regime). This had provoked such a reaction of the workers, who still had recent memories of the fascist regime, that the ruling class had to abandon that ‘experiment’, and within a few months the government collapsed.

We need to remember that there were two sides to the impact of the postwar boom. On the one hand there were more jobs and growing living standards, but there was also the actual numerical strengthening of the working class, which gave it greater weight in society. This gave the workers, in particular the youth, a renewed confidence. This explains the militant movements in 1962-63. And this needed to be taken into account by the ruling class.

The PSI openly collaborates

Having failed in their attempt to lean on the MSI, the ruling class was forced to look to the left for a helping hand. Thus, the PSI with its 87 MPs was called on to provide a stable parliamentary majority. This was the beginning of what would be known as the ‘centre-left’ coalitions that would govern Italy until 1972.

In 1963, however, the PSI was divided on the question of whether to join the coalition government, and this was clearly seen at its national congress that year. The left wing of the party rejected a coalition with the Christian Democracy, preferring an alliance with the Communist Party. There were in fact two major documents presented to the congress, one supporting the entry of the party into a coalition with the Christian Democracy (that gained 57.4 percent) and another opposing (winning 39.3 percent), with a very small minority of 2 percent calling for party unity.

The left wing of the party would go on to split away at the beginning of 1964 to set up the PSIUP (Italian Socialist Party of Proletarian Unity) and would move quite radically to the left. It is worth noting that the PSI lost about half its trade union cadres to the newly formed PSIUP, and practically the whole of its youth, which shows how deep the opposition to collaboration with the Christian Democracy was in a significant layer of the rank and file of the party.

Now, where did Riccardo Lombardi stand in the key decision taken at the 1963 congress? We should remember that he was seen as a leftist in the party. His intervention in the debate at the congress is therefore worth quoting at length, as it reveals how deep the illusions in capitalist development had gone.

He began his speech stating that the party should be open to participating in a coalition government, thus backing the majority right-wing faction in the party, when he could have backed the left wing and possibly defeated the attempt to shift the party to the right. But he did not, and instead he argued that because capitalism was developing, if the party wanted to have some influence on the direction of that development it could only do this by being in the government. The speech reflects the impact the postwar boom was having on the reformists:

“Whether we want it or not, comrades, if we are Marxists [!], we must start from the objective consideration of the facts as the robust and healthy pedagogy of Marxism teaches us. We must start from the assumption that Italian society will only slightly resemble today’s society in five years, certainly in ten years: over the course of these years a process of transformation will have matured and completed which will give life to a model which after those five or ten years we will no longer be able to modify except through enormous difficulties.

“Comrades, if we were faced with a situation from other times, not of neo-capitalism but of paleo-capitalism, we could calmly wait for the internal contradictions of capitalism and the fact that it cannot provide an answer to the elementary needs of employment and income of workers to bring the situation to a level of struggle capable of modifying and removing the existing balance. But we live in a neocapitalist climate… And neocapitalism has the ability – in its own way, with very high social costs certainly – but it has the ability to provide an answer to the elementary problems, and also to the problems that go beyond the elementary ones, of the working people.

“Today neo-capitalism is capable of giving an answer to the problem of employment, it is able to ensure a minimum level of income, a certain type of capital accumulation, expansion of the economy and distribution of income…” [My emphasis]

As you can see, he is arguing that “neo-capitalism”, as he calls it, does not follow the logic of “paleo-capitalism”, the old capitalism to which one could apply the analysis of Marx, but has a new dynamic which can be influenced positively if the PSI were in the government. The postwar world upswing of the capitalist economy further strengthened his view that Marxist economic theory only applied to the capitalism of the past. Now this “neo-capitalism” did not have the same contradictions.

The irony of all this is that over the following decade Italy would indeed see dramatic changes, but not the ones envisaged by Lombardi. It would be the decade of the 1968 youth protest, the explosion of the class struggle in the Hot Autumn of 1969, and the deep crisis that the capitalist system would enter in 1973, revealing that all the contradictions within the system had not been eliminated – but more on this later.

In his 1963 speech he explicitly stated that “…the socialists cannot expect their programme to be accepted en bloc…” and he said quite clearly that “the programme that we are presenting is not a socialist programme: it is simply a democratic programme of renewal…” (Minutes of the 35th National Congress of the PSI held in Rome, 25-29 October 1963).

Compare all this to the absolute clarity of a genuine Marxist, Ted Grant, in his text Will there be a slump?, written in 1960. Ted Grant did not limit himself to looking at the superficial, but looked deeper. In spite of the powerful postwar boom taking place at that time, and all the illusions of the reformists that came with it, Ted explained that the upturn would inevitably end at some point, and would be followed “by a catastrophic downswing, which cannot but have a profound effect on the political thinking of the enormously strengthened ranks of the labour movement”. [My emphasis]

The end of the postwar boom and the explosion of class struggle

This is precisely what happened in the 1970s. The situation changed dramatically in the decade following Lombardi’s 1963 speech, and Italy was one of the countries where the class struggle would prove to be most intense. The boom had strengthened the working class, which was starting to find its feet again after the defeat of the revolutionary movement of 1943-48.

Millions of peasants had moved into the cities, in a widespread process of urbanisation. There had also been a rejuvenation of the working class itself, with huge numbers of youth entering the factories. In the period 1951-61 around two million people left the south – 12 percent of the population – a large number moving to the Turin-Genoa-Milan ‘industrial triangle’ in the north.

An anticipation of what was to come had already been seen in the strikes of 1962-63. But this was temporarily cut across by a slight slowdown in the economy, which would speed up again by 1967. This recovery is what prepared the huge explosion of class struggle in the famous Hot Autumn of 1969.

An anticipation of the degree of radicalisation which was about to take place was seen in France in the May 1968 general strike, which was also accompanied by factory occupations. That year saw a flowering of left groups in Italy, especially among the youth.

In the meantime, the PSI was about to pay a price for its years of collaboration with the Christian Democrats. Whereas in 1968 it won 14.5 percent in the elections, in 1972 its vote went down to 9.6 percent. This led to a discrediting of the old right-wing leadership, together with a strengthening of the party’s left wing.

Lombardi had meanwhile been marginalised within the PSI due to his later opposition to the policies of the centre-left government. At a key moment – the 1963 party congress – he threw all his weight behind the majority document in favour of joining the coalition with the Christian Democrats. But he then later became critical of the actual policies of that government.

However, he was very active in conferences, debates, assemblies, and initiatives of all kinds. He was a well-known figure in supporting North Vietnam against US imperialism. He was very vociferous in the ongoing campaign for the right to divorce, and on many other issues. And as Giuseppe Sircana explained in 1995, commenting on Lombardi in the Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. LXV, this made him “one of the politicians most receptive to the calls for renewal advanced in the late 1960s by the student and labour movements…”

And shortly after the PSI’s electoral debacle in 1972, the postwar upswing finally came to an end in the 1973-1975 downturn. All major capitalist economies saw a significant fall in GDP in those two years. Italy experienced a severe crisis in 1974-1975, with a significant fall in GDP of 3.5 percent in 1975. Inflation surged from around 10-11 percent in 1973 to 19-21 percent in 1974, hitting 25 percent in early 1975. Unemployment also started to rise from the mid-1970s onward – eventually peaking at over 13 percent by the 1980s.

As we can see, the objective situation was now very different from what it had been just a decade earlier. And it was not what Lombardi had predicted in his 1963 speech. How did this impact on the ideas he began to express in the 1970s? Like a chameleon, he was once again changing his outer colouring, adapting to the new environment. He declared the experience of the centre-left governments a failure, and he was no longer talking about a capitalism that had solved its internal contradictions.

Lombardi turns left

To provide our readers with a taste of what he was now saying, it is worth quoting at length from an interview with Lombardi by Carlo Vallauri, published under the title ‘L’alternativa socialista’ in 1976. Here we find a very different Lombardi from that of 1963. Right at the beginning we find Vallauri posing the question as to what the socialist alternative means for him. His answer is the following:

“It’s not about creating an alternative for better governance; it’s not about having a good government rather than a wasteful one, or a more reformist, or more honest one… What I call a left-wing alternative is an alternative aimed at ushering in a period of gradual transition to socialism.”

He no longer spoke of the capitalist system as having solved the basic problems of the working class. He was now saying:

“I believe those who think this crisis can be fixed are mistaken. I’m not saying capitalism is dead; it may be, like all systems, destined to die, but all monsters, before dying, have dangerous aftershocks that need to be considered.” And he added, “Capitalism can be followed by socialism, but it can also be followed by barbarism.”

As we can see, this is much more radical talk than what he was saying in 1963. In the interview he quotes Lenin more than once, specifically on the nature of the trade unions, and on what defines the class nature of a party. He explains that capitalism can no longer govern in the old ways, that it can no longer guarantee the material benefits that it once did. He quotes Trotsky’s analysis of the middle classes and how to win them over, as being the most valid. He states that Trotsky’s is the “the most intelligent and penetrating analysis” on this question. He had in fact looked into Trotsky’s analysis of the Soviet Union in the 1930s, although he did not agree with all of its conclusions.

And he criticises the Communist Party from the left. We have to remember that in this period the leadership of the PCI under Enrico Berlinguer had adopted its famous policy of the ‘Historic Compromise’, which envisaged a government alliance with the Christian Democracy. In effect, the PCI leaders were preparing to play a role similar to the PSI in 1963, one of class collaboration and compromise. This was applied concretely in the years 1976-79, and proved to be a disaster, marking the end of the working class upsurge that had started with the Hot Autumn of 1969.

Lombardi, however, clearly poses the alternative as being one based on unity between the PCI and PSI. And he adds that the Communist Party’s policy of governing with the Christian Democracy, a bourgeois party, implies giving up on the socialist transformation of society, whereas he insists on the need for such a transformation.

However, at the same time, we should never lose sight of the fact that, in spite of all the radical sounding left rhetoric, he never abandons his gradualist, reformist approach. He refers to a left that, “intends to radically modify society, even though in a gradual manner…” [My emphasis] We have seen how he refers to Marxism, even quoting Lenin and Trotsky, but he is still the Lombardi that was influenced by bourgeois, idealist philosophy in his youth. In the 1976 interview he states:

“Without being intimidated by accusations of revisionism… I must say that the need to review and update Marxian concepts in the context of today’s society and its profound transformations, compared to the society in which Marxism was developed and conceived, is not only imperative, but is happily being implemented.”

To cover his left flank, however, he states that the kind of revision of Marxism that he envisages has nothing to do with the “Bernsteinian and Social-Democratic” of the late 19th century.

The interviewer asks Lombardi a straightforward question: “do you consider yourself a Marxist?”. Lombardi replies that he cannot give a yes or no answer because there are many “marxisms”. He says that Marxism is a useful tool, but he quotes yet again Benedetto Croce!

In spite of this, his left-wing language, with all his talk of a transition to socialism, placed him in the position of becoming the unquestioned leader of the left wing of the PSI in the 1970s. And this made him a point of reference for a significant layer of the youth in the radicalised atmosphere of that period in Italy.

As Lombardi shifted to the left, a significant layer of youth who had previously been in groups such as Lotta Continua, the Manifesto group, and Avanguardia Operaia, began joining the PSI. Even some elements from a particularly ultra-left grouping, Potere Operaio, joined. This strengthened the youth wing of the PSI, the FGSI (Federazione Giovanile Socialista Italiana). The party’s worker base was also strengthened in the process with its workplace cells, the Nuclei Aziendali Socialisti (NAS), seeing significant growth.

This shows that the radical left language of a leader like Lombardi was having a real impact in attracting workers and youth to the party. There was tremendous enthusiasm, and many in the rank and file were pushing for Lombardi to become the national secretary of the party. But this was not to be.

And then he tacks right again

In the very same year of the interview quoted above (1976), the PSI in the aftermath of its electoral weakening saw an internal struggle between its various factions as to who should be the new national secretary. It was in fact a struggle between the left and the right factions that were fairly evenly balanced. In the end a compromise was reached and Bettino Craxi was elected leader.

Craxi was supposed to be a temporary ‘transitional’ figure, but he would go on to take full control of the party, shift it back to the right and return to coalition governments with the Christian Democracy in the 1980s. Craxi would go on to become prime minister and destroy the PSI in the early 1990s as it was so heavily involved in one corruption scandal after another.

In all this, Craxi was aided, albeit indirectly, by Lombardi who backed his election as party secretary and swung the whole of the left wing of the party behind this decision, which thus provided a huge majority. Two years later, in 1978, the national congress of the PSI adopted Craxi’s ‘Progetto socialista per l’alternativa’, which Lombardi supported, arguing that this was a way of influencing its direction. Like a chameleon, Lombardi changed his colour once again, this time tacking to the right.

Lombardi would shortly afterwards become critical of Craxi, but the damage had by then been done. All those rank and file members who had joined the party enthused by the radical talk of Lombardi were hugely disappointed, and they began to leave. The youth wing, the FGSI, also went into decline, and in many areas disappeared from the scene.

What I have tried to show in this article is that reformists can swing to the left and to the right, depending on the objective situation and the different pressures they come under. Some of them can actually swing very far left, adopting revolutionary sounding phraseology.

When this happens, all those on the left looking for a fighting leadership can have their hopes raised and they can rally round these left reformists. But because of the underlying reformist outlook of these leaders, they inevitably succumb to the pressure of the class enemy, the capitalist class, and its political representatives, and end up changing their colouring.

Thus, their role, objectively speaking, is to gather together the leftward-leaning activists in the labour movement and hold them within the limits of a reformist outlook. At a crucial moment, they betray their own supporters, disappoint and demoralise them, and then hand the reins back to the right wing of the movement and thus save capitalism from the wrath of the working class.

We have to learn to distinguish between the reformist chameleons and genuine, revolutionary Marxism. Marxists do not change their colour as the environment changes. Marxists think ahead, they look at the underlying contradictions of capitalism and where these will inevitably lead, and they prepare.

Reformists seek change within the confines of the existing capitalist system but without breaking with the bourgeoisie. Because of this, they are blown hither and thither without a compass, without a real sense of where society is going. And that explains why they are incapable of offering a way out when the inevitable crisis of capitalism hits.

Marxists, on the other hand, seek to provide a scientific explanation of society at all times, during both the ups and the downs of the cycle of capitalist development, and to prepare the masses for the proletarian revolution of the future. It is the only way. We are not political chameleons, and we do not change our colour, which remains red at all times.