Readers in Quebec and Canada can purchase this magazine from the Camilo Cahis Publishing House here.

A hundred years ago, in the midst of the First World War, an anonymous pamphlet under the pen-name ‘Junius’ appeared in Zurich and rapidly began to circulate throughout the international workers’ movement. This pamphlet had in fact been written from inside a German prison cell by Rosa Luxemburg.

[We publish here the editorial of issue 52 of ‘In Defence of Marxism’ magazine – the quarterly theoretical journal of the Revolutionary Communist International. Get your copy now!]

In it, she wrote:

“Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads, either transition to socialism or regression into barbarism.”

This bold prediction, which she attributed to Friedrich Engels, has become one of the most widely recognised slogans of the Marxist movement: ‘socialism or barbarism’.

These words have retained all their force today. They perfectly capture the period in which we live: a social system in an advanced state of decay; a degenerate ruling class that is incapable of addressing the problems of humanity; and a life-or-death struggle on the part of the oppressed to throw off the old order, in which the working class must either emerge victorious, or face ruin.

It is this reality that has been so starkly illustrated in Sudan today, and to which the present issue of In Defence of Marxism is devoted.

Rise and fall

Contrary to the once common liberal idea, history is not a continuous and gradual ascent along the high road of human progress. History knows a descending curve as well as an ascending one, great leaps forward and dramatic collapses.

Visit the majestic but desolate ruins of the great Mayan cities, or stand atop the remains of Hadrian’s wall – built to establish the outer limit of the Roman Empire – and you will catch a glimpse of the great dialectical law of history: ‘All that exists deserves to perish’.

But it is not enough simply to observe the fact that civilisations have come and gone before our own; it is necessary to understand why. For hundreds of years historians and philosophers have puzzled over this question. Indeed, the BBC has recently released a series called ‘Civilisations: Rise and Fall’ on precisely this subject, dealing with the collapse of Rome, Ptolemaic Egypt, the Aztec Empire, and Japan’s Tokugawa Shogunate.

To say nothing of the content of this series (and the less said about it the better), what is most striking is the fact that the parallels with today are so openly acknowledged. Take one review in The Guardian, for example, which is titled: ‘TV that will make you despair for our own plummeting society’.

The decline and collapse of civilisations is often explained away by reference to bad leadership, such as incompetent or insane emperors, or to external causes like natural disasters and plagues. While these play a role, the irreversible decline of an entire civilisation cannot be explained simply by the errors of individuals. Such an explanation only raises the question: ‘Why did their leaders keep making mistakes?’ – a question many ask about our own rulers today.

Karl Marx discovered the fundamental process which ultimately determines the rise and fall of civilisations, and set it out in a few brief but brilliant strokes in his Preface to a Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, published in 1859, the same year as Darwin’s Origin of Species.

Applying a scientific approach, Marx identified that every social formation arises on a material foundation: not just environmental conditions, but a definite set of relations between human beings, through which they produce the necessities of life in accordance with the level of technology already acquired.

For a time, the spread of these relations of production, and of the entire social, political and ideological order that arises on this material foundation, greatly accelerates the development of the means of production, science and technique: in short what are referred to as the ‘productive forces’. And as the productive forces develop, they in turn reinforce the rising order, which sweeps everything before it.

History is full of examples of this phenomenon: the spread of agriculture during the Neolithic Revolution; the emergence of states and class society during the Bronze Age; the rise of the slave system, of ancient Europe and the Mediterranean; the ‘medieval boom’, which followed the consolidation of feudalism; and of course, the unstoppable rise of modern industrial capitalism. And this is by no means an exhaustive list.

But all things eventually turn into their opposite. As Marx explains, the productive forces that have been developed under the existing order become too powerful, too broad for the narrow confines of the existing relations of production and exchange.

In such periods, the maintenance of the old relations becomes an increasingly painful fetter on further development. Meanwhile, what economic development that does take place leads not to a strengthening of the existing order but undermines it, producing crises, wars and revolutions.

The Roman slave economy decayed, and it was out of that decay that feudalism eventually emerged. Likewise feudalism thrived in Europe for centuries, only to enter into its own period of decline, in which the foundations of capitalism were laid. Thus, within the rise of every social system are the seeds of its eventual decay, and every decline contains the seeds of future progress, however remote that may appear.

Imperialism

But what of capitalism? Given the fact that the world economy has grown many times over the last century, in what sense can we speak of the decline of the capitalist system today? The answer lies in the nature of imperialism, described by Lenin in his book, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, written in the same year that Luxemburg’s pamphlet was published.

Imperialism is not simply one nation dominating the other, as is commonly understood by the term; it is a stage in the development of the world capitalist system, one in which capitalist relations have turned into their opposite.

So-called ‘free competition’ between capitalist firms has been replaced with the domination of the market by a series of giant banks and monopolies, which are indissolubly tied to the state. This applies just as much to countries where the role of the state is openly acknowledged, such as China, as it does to the USA, supposedly the home of ‘free enterprise’.

The rise of planning within monopolies does not do away with the anarchy of the market; it exacerbates it, leading to ever deeper crises. At the same time, concepts such as the ‘creative destruction’ and ‘invisible hand’ of the market have been replaced in practice by companies that are ‘too big to fail’, receiving bailouts, subsidies and lucrative state contracts, all funded by eye-watering levels of public debt.

Consequently, the capitalist class itself has become utterly parasitic. What development that does take place is largely dependent on the state, and carried out not by the bosses but by an army of wage workers. Rather than being strengthened by such development, the ruling class only becomes more redundant.

This can most clearly be seen in the old imperialist powers of Europe, where the ruling class has presided over decades of economic stagnation, deindustrialisation and crumbling infrastructure. But the signs of capitalist decay can be seen everywhere, not least in the indescribable levels of inequality.

In truth, never in history has there been a ruling class that is so parasitic, so detached from reality, and so ripe for overthrow.

Naturally this is reflected in the intellectual, moral, and even psychological degeneracy of the ruling class. This is epitomised by the banker-sex trafficker, Jeffrey Epstein, whose seedy network of ‘clients’ encompassed a large part of the wealthiest and most powerful families in the Western world. And that is only the tip of the iceberg.

The domination of the world by imperialism also brings the scourge of war and genocide on an unprecedented scale. In this sense, the highest level of civilisation yet achieved by humanity necessarily produces its opposite: barbarism.

This has been the case throughout the history of modern, capitalist imperialism. At the dawn of the imperialist era, the Berlin Conference of 1884 set down the infamous doctrine of terra nullius – ‘nobody’s land’ – under which states were destroyed and populations wiped out in order to clear territory for the European imperialist powers.

Driven by the insatiable hunger of the monopolies for resources, markets and fields for investment, the ceaseless struggle of the most powerful capitalist states to carve up the globe led to the carnage of two world wars, which together claimed the lives of more than 100 million people.

And even during the golden age of the so-called ‘Pax Americana’, the world witnessed a war of extermination waged by US imperialism against the people of Vietnam, the barbarity of which was summed up in the phrase of one American general: “We’re going to bomb them back into the Stone Age”.

Today, we have no shortage of examples of the barbarism fostered and spread by imperialism. In the horror inflicted on the people of Gaza, of Darfur and of eastern Congo, we clearly see the profound truth of Luxemburg’s warning:

“The victory of imperialism is the annihilation of civilisation”.

And if capitalism is allowed to continue destroying the environment, then it may be confirmed in the most complete and literal sense imaginable.

Class struggle

Such is the horror produced by the crisis of capitalism today, many people have lost all belief that it is possible to make any rational sense of the world. This in turn has fuelled a rising interest in religion and conspiracy theories. Many even speak of the end of the world, whether due to some rogue AI, nuclear war, or any number of causes.

This apocalyptic dread is not new; it was common in the waning days of feudalism in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. But that was not the end of the world, only the death of an obsolete order.

In such periods, progress means escape from the wreckage of a sinking system, and the establishment of a new order, based on fundamentally different relations.

This clearing of old defunct relations and the unleashing of mankind’s productive forces is the essence of social revolution. But revolutions are not carried out by the productive forces themselves, nor by ‘humanity’ or ‘history’ in the abstract. They are carried out by living human beings, divided into classes with opposing interests.

Marx noted that humanity only sets itself “such tasks as it is able to solve”. As any social system flourishes it creates the material forces required for its overthrow, including new social classes capable of bringing a new social order into fruition. Under feudalism it was the bourgeoisie. Today it is the working class that embodies the hopes of humanity.

This is not simply an article of faith. The working class produces almost all of the world’s wealth. Many times throughout history the workers have shown themselves capable of taking over production and organising it even more efficiently, without the unnecessary cost of bosses and landlords.

Moreover, ever since its arrival on the scene of history, the working class has been driven by the logic of its class position into struggle against the ruling class and the established order, placing it at the forefront of every movement for liberation and progress.

‘Socialism or barbarism’ therefore signifies that only the seizure of power by the working class can defeat imperialism and at last overthrow the decaying capitalist order. But it must also be recognised that the ruling class will stop at nothing, even at the risk of undermining its own civilisation, in order to crush the emergence of a new society within the old.

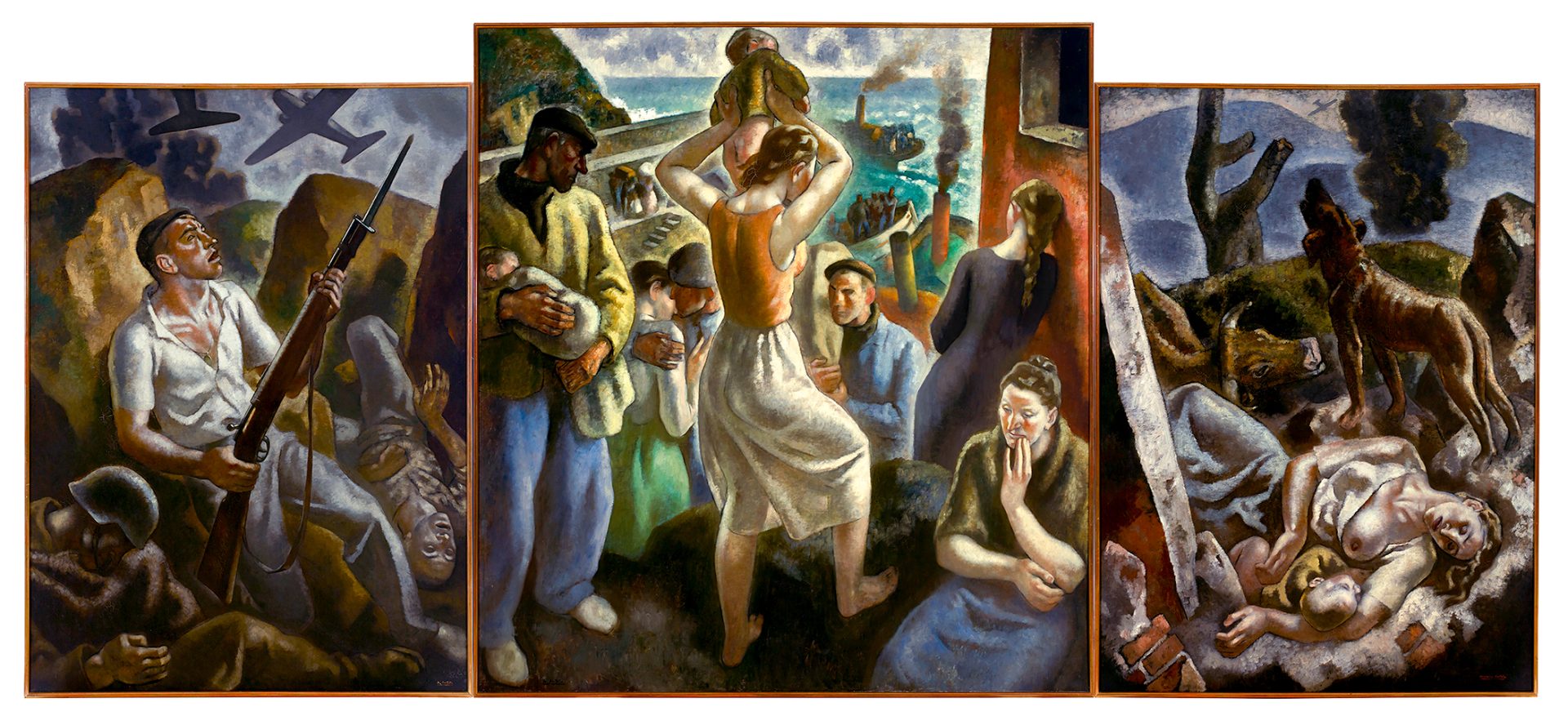

When the workers of Paris were massacred in 1871, the killing was so savage that even the respectable bourgeois press pleaded with the authorities to stop, as the stench of the corpses was so overpowering. In the twentieth century, the European bourgeoisie was prepared to unleash the monster of fascism on Europe in order to liquidate the workers’ movement, rather than risk its own overthrow.

Likewise, in the recent period, the Sudanese ruling class was more than willing to use the Rapid Support Forces as its attack dogs against the revolutionary movement. For years this reactionary paramilitary force was groomed and funded not only by the Sudanese state but by a host of foreign powers. The result has been the destruction of the country.

The fate of Sudan should serve as a warning: any revolution that stops short of the complete overthrow of the bourgeoisie and its state is preparing for disaster.

The party

It might reasonably be asked, if the working class is truly capable of overthrowing capitalism and leading society out of the decaying capitalist order, why has this not been achieved already?

Certainly, the survival of imperialism cannot be put down to any lack of courage or determination on the part of the workers when they enter onto the road of revolution. Over the last 100 years, almost every country on the planet has been rocked by inspiring movements of the masses, which have posed the question of power point blank.

However, the vast majority of these movements have not led to the overthrow of capitalism. And what the experience of the last century has proven beyond all doubt is that the power and heroism of the masses, while absolutely essential for any revolution, are not enough by themselves.

What is needed is organisation and, above all, a leadership capable of facing up to the immense tasks of history, and bringing the struggle to a victorious conclusion. And it is this decisive factor that has tragically been lacking in so many cases.

This is not simply down to accidents or individual mistakes. As the masses move into struggle it is natural that they first look to well-known figures or organisations, or those that offer the path of least resistance. But these tend to look to the past, or are completely bewildered by the situation.

Through their own experience of events, workers and youth learn hard-won lessons and begin to draw revolutionary conclusions. But if no alternative leadership exists to give expression to these conclusions, it cannot be improvised in the moment. As a result, the movement will reach a dead end, as it did in Sudan.

The critical task of the revolutionary party is to be able to connect with the developing consciousness of the masses and win the leadership of the movement in time, before the forces of counter-revolution are able to pacify or crush the movement.

This is no simple task, and so it requires that such a party be built before the volcano of revolution erupts. In his reply to Luxemburg’s ‘Junius’ pamphlet, Lenin recognised the urgency of building such an organisation, when he wrote:

“A very great defect in revolutionary Marxism in Germany as a whole is its lack of a compact illegal organisation that would systematically pursue its line and educate the masses in the spirit of the new tasks…”

These words would carry a heavy significance during the German Revolution of 1918. Luxemburg and other revolutionary Marxists began the crucial struggle to build a revolutionary leadership when they founded the Communist Party of Germany in December 1918. But by then the revolution had already broken out, and the revolutionaries were dealt a heavy blow with the brutal murder of Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, less than a month later.

The tragedy of the German Revolution has been repeated many times. The inspiring revolutionary wave that swept Europe at the end of the Second World War could have fundamentally changed the course of history, but it was deliberately blocked, and diverted into ‘safe’ channels by its own leadership.

Even in the United States, the greatest imperialist power on the planet, had a sizable revolutionary communist party been built during the tumultuous years of the 1960s, capitalism might have been overthrown.

Between 2019 and 2021, the workers and youth of Sudan had power within their reach. That they did not seize it is solely down to their leaders, who constantly held back the movement in order to keep it within the bounds of a gradual and peaceful transition to democracy – a transition which was completely ruled out by the nature of Sudanese capitalism.

One cannot help but think back to the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s. The Spanish masses could have taken power many times over, but they were held back by their parties in the name of ‘order’. The result was unimaginable horror, as it is today in Sudan.

The historic dilemma of ‘socialism or barbarism’ thus resolves itself into the practical political question of the revolutionary party.

No time to lose

Barbarism is not only a future prospect; it is spreading now. But this is no reason to abandon hope.

Returning to Marx’s profound statement – “Mankind thus inevitably sets itself only such tasks as it is able to solve” – the potential for a worldwide revolutionary party of the working class exists everywhere. In fact, it has never been greater.

On a global scale, the working class has never been stronger. Meanwhile in most of the world the ruling class is the weakest it has been for decades, and a whole generation is being radicalised under the banner of the ‘Gen Z revolutions’.

The working class and the oppressed masses of the world will not allow the ruling class to drag us down to hell without a struggle, which will put all the revolutions of the past in the shade.

The tasks of Marxists today are to get organised; to reach the most advanced layer of the workers and youth; to build parties of thousands of steeled communist revolutionaries, ready and able to connect with the struggle of the masses during the titanic struggles to come; and finally to lead the way to the seizure of power by the working class.

If history has taught us anything, it is that this task will neither be easy nor straightforward. But there is no greater cause on earth.

Sudan has shown us the stakes. Let us go forward, fully conscious of the challenges that impend, and doubly determined to smash all obstacles in our path.