The period of 1980 to 1981 in Poland was marked by the most intense confrontation between the working class and the Stalinist bureaucracy in history. The working class attempted to take control over the commanding heights over the economy and purge the Stalinists, whose incompetence and betrayal of the ideals of real socialism had brought the country to ruin. It is the task of genuine Communists to retrieve the revolutionary heritage of this period from under a mountain of lies of both capitalists and Stalinists, who disregard the genuine experience of the working class in this period, and slander the revolution itself.

There is no doubt as to the enormous significance of this movement. American historian David Ost correctly observed that Poland at the time “resembled Paris in 1968, Barcelona in 1936 or even Petrograd in 1917”[1] . In the words of Karol Modzelewski, one of the key figures in Solidarność at the time, “this was the largest workers’ movement in the history of Poland, and perhaps Europe too”[2].

Both of these people are correct. However, as Marxists, we observe another crucial significance to this movement: it was one of the most advanced attempts of the working class in the history of Stalinist countries at fighting for a healthy, democratic workers’ state, as opposed to the caricature of socialism created by the Stalinists. The victory of Solidarność in 1980-1981 would have been a tremendous victory for the working class. It would have sparked a world revolution, both in the East and the West.

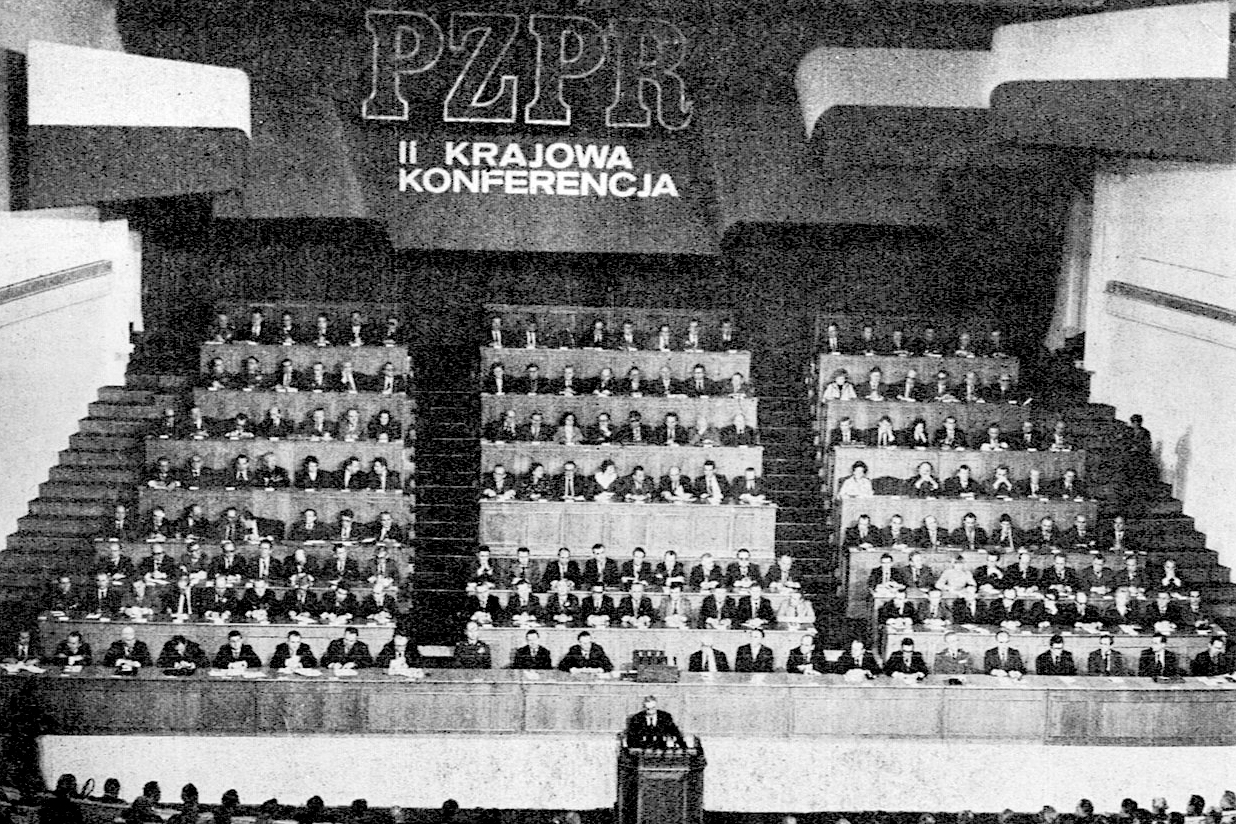

The revolution was divided into two main camps. On the one hand, there was the Stalinist bureaucracy, which used the planned economy to enrich themselves while suppressing the working class’ freedom of organisation and speech. They did this through Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza (PZPR, Polish United Workers’ Party), as well as the repressive, totalitarian state apparatus. On the other hand, there was a mass movement of the working class, with its vanguard in the shipyards of Gdańsk and Szczecin, as well as other heavily industrialised cities. They organised themselves in Międzyzakładowe Komitety Strajkowe (MKS, Interfactory Strike Committees) and Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy “Solidarność” (NSZZ Solidarność, Independent Self-Governing Trade Union “Solidarity”). In a short period of time, the Union had almost 10 million members, almost two-thirds of the country’s workforce, and one third of the entire population. This did not include the supportive students, farmers, tradesmen and other layers. The sheer scale of the movement was just one of its several unprecedented features. There is no prior historical parallel for such rapid, voluntary and sustained mass unionisation.

Unfortunately, despite a heroic battle which lasted 16 months, no dual power situation can last indefinitely. It was impossible for Poland to remain half a totalitarian state, and half a free, organised working class. As Ted Grant, the leader of our movement stated in August 1980 in The Militant: The movement was bound to end with either Solidarność taking power or being crushed by the bureaucracy.

The long term crisis of Polish Stalinism

Before delving into the revolutionary period itself, it is necessary to contextualise the nature of the Polish regime, as well as the experience of the Polish working class. By August 1980, Poles had experienced 35 years of Stalinist rule, which was imposed on Poland in a top-down manner by the USSR after the Second World War. The Polish People’s Republic became an extension of Soviet Stalinism, formed in the image of Moscow of 1945, rather than Petrograd of 1917.

The original aim of Lenin and the Bolsheviks was an international proletarian revolution, leading to a classless society based on superabundance and the withering away of the state. Following the defeats of various revolutions in the interwar period, and the isolation of backwards Russia, a bureaucratic clique emerged around Stalin in the Communist Party. Lenin’s last struggle was against the danger of bureaucratic degeneration of the state and the communist party. Stalin’s bureaucratic and chauvinistic handling of the Georgian crisis convinced Lenin that these bureaucratic tendencies risked taking over the party. Unfortunately Lenin’s health deteriorated and he died before he could wage that battle. However, his last correspondence leaves no doubt about his intentions.

The struggle for preserving the revolution against degeneration raged throughout the 1920s. Defeats and setbacks for the world revolution in Germany, China and Spain allowed the bureaucracy under Stalin’s leadership to defeat the Left Opposition led by Trotsky and consolidate itself. This meant ruthlessly strangling any elements of workers’ control and reversing any social and cultural gains, culminating in the Stalinist purges of the 1930s. Trotsky was exiled and eventually killed, as were most of the old Bolsheviks.

Stalin’s purge included a massacre of many leading and rank and file members of the Communist Party of Poland, leading to the collapse of the Party in 1938[3]. Amongst the murdered were many important leaders of the Polish Communist movement. Those included Adolf Warski, the founder of the Communist Party, Julian Leszczyński, veteran of the October Revolution and former Executive Committee member of the Comintern, Tomasz Dąbal, former Polish Communist MP and leader of the former Polish peasant-soviet republic in Tarnobrzeg, and Maria Koszutska, a veteran of the party and the Polish Workers’ Councils of 1918-1919. The Stalinists also ruthlessly executed Polish rank and file Communists in their thousands , including veterans of the Red Army during the Russian Civil War and militant activists of the Polish labour movement who sought refuge in the USSR from Sanacja (the Polish bonapartist dictatorship of Józef Piłsudski, which locked up political opponents in concentration camps, most notably in Bereza Kartuska).

Poland has been home to some of the most remarkable revolutionaries. Polish fighters played vital roles as internationalist allies of both the French and Haitian revolutions, standing in solidarity against oppression across continents. During the brutal suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871, the forces of reaction executed countless Poles – often regardless of their individual beliefs – on the assumption that their very nationality signified revolution. In the early 20th century, the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania, led by figures like Rosa Luxemburg and Julian Marchlewski, championed a radical workers’ movement at the heart of Europe, becoming reliable allies with the forces of Russian Bolshevism. Stalinism sought to drown this kind of revolutionary legacy in blood, not just in Poland, but across the world.

Though the Polish Communists were some of the first victims of Stalinism, the chauvinistic treatment of Poles by the Stalinists continued: Polish autonomous zones in the USSR were ethnically cleansed; innocent Poles, including children, were deported en masse to Siberia; the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which agreed to carve up Poland with the Nazis, was signed; tens of thousands of Polish state officers and intellectuals were murdered in the Katyń Massacre; and the Nazis were allowed to slaughter the heroic Warsaw Uprising, as the Red Army was instructed not to help the Warsaw partisans.

These scandalous crimes affect Polish consciousness to this day. The methods of the Stalinists had more in common with methods of the Tsar than the internationalist approach of Lenin, Trotsky and the Bolsheviks, who struggled for Poland’s right to self-determination against its imperialist partitioners. Unlike Stalin, Lenin consistently defended the right of oppressed nations to secede from the Russian state – even when it was politically inconvenient – and opposed Great Russian chauvinism in both word and deed.

Leon Trotsky described the USSR under Stalin as a degenerated workers’ state. Trotsky concluded that Stalinism was not an inevitable outcome, but rather a product of Russia’s backwardness and isolation, as the insufficiently developed productive forces, education and level of technique could not guarantee the material conditions for abundance and the overcoming of class divisions in society. The only way out would have been international revolution, but the crucial defeats in Germany, China and elsewhere allowed the bureaucracy to consolidate its power under Stalin. Trotsky stated that the Soviet bureaucracy needed to be overthrown by a mass workers’ movement, which would rejuvenate democracy via trade unions and workers’ councils, implement freedom of speech, purge the state apparatus and carry out serious reforms to the pre-existing planned economy. If the workers failed to do that, Trotsky predicted that the bureaucracy would participate in the restoration of capitalism[4]. All of Trotsky’s works were completely banned in Eastern Europe under Stalinist rule. Trotskyists were treated as the most dangerous of all dissidents, often receiving the worst treatment.

The Polish People’s Republic was a de facto one party state led by PZPR, with a nationalised economy centrally planned by the party. The planned economy’s superiority over the market economy gave it a genuine base of support in society. The state could prioritise its resources in a more efficient manner, rather than leaving post-war reconstruction to the invisible hand of the market, which is only interested in production as long as it brings profit to the capitalists. The country was rebuilt rapidly after the extreme destruction of WW2. Industry was built up, illiteracy was eliminated and the standard of living of many Poles improved when compared to the pre-war Sanacja regime. It is impressive, for instance, that Poland was able to remove the post-war food rationing system before one of the world’s leading imperialist powers, the United Kingdom. As a result, there was a mass basis of support for PZPR in Polish society at the time, in spite of its totalitarian tendencies.

This state of affairs started to dissipate, however, as the bureaucracy showed its true colours. The main problem faced by the planned economy was the exclusion of the Polish working class from all decision-making in a state which was supposedly run in its interests. All elements of workers’ power were quickly defanged or dissolved.

The working class tried to fight this state of affairs on numerous occasions. For instance, the workers of Poznań began a general strike in June 1956, seeking economic and social improvements for their situation. Rady Robotnicze (RR, Workers’ Councils) emerged organically in the course of this movement, which inspired the Hungarian Revolution which broke out in the same year. In Poland, the workers’ mass movement threw its support behind the previously imprisoned Władysław Gomułka, who became the new leader of PZPR and promised reforms.

Ultimately, the workers’ councils were stripped of any semblance of power following the reforms of 1958[5]. The reforms co-opted the RRs into Konferencje Samorządów Robotniczych (KSR, Conferences of Workers’ Self-Governance) and made them subordinate to the representatives of management and the PZPR[6]. These organs were used tokenistically by the bureaucracy. Publicly, they praised these organs. However, in practice, they used them in a consultative capacity at best. More often than not, Party officials and management used various manoeuvres to ensure that these organs had no real power. In some of the most economically important industries, they were completely disbanded[7].

In effect, all levers of the economy were firmly in the hands of a bureaucratic caste of managers and party officials, whose living standards were high above those of the working class. The maintenance of this rule was possible only through intense propaganda, censorship, and a powerful state apparatus of repression that was used against any opposition activists.

Another attempt of the working class to emancipate itself was carried out by the coastal workers of Gdańsk, Gdynia and Szczecin. They created new organs of workers’ power, though they were brutally crushed in December 1970. In Gdynia, the striking shipyard workers were asked by PZPR bureaucrat Kociołek to return to work. The next day, the workers were massacred with machine guns while on their way back to work. In Szczecin, the shipyard workers marched on the city centre singing ‘The Internationale’, before riots erupted and the forces of the state opened fire, killing and wounding many workers.

Following these events, the Szczecin working class, through the self-organised workers’ committees – the MKS – effectively paralysed the local authorities, and for several days, exercised de facto control over the city’s industrial and social life. The MKS coordinated essential services, maintained order, and negotiated directly with the government, leaving the official authorities largely powerless until the state ultimately regained control due to the movement’s isolation.

The economic crisis

The Stalinist mismanagement of the planned economy continued to make the situation less and less tolerable. The 1970s were defined by heavy borrowing, and an increased dependence on foreign capital. The national debt between 1971 and 1980 grew by more than 2250 percent[8]. By 1978, the debt became unsustainable, as the amount of debt was three times larger than the value of total exports to capitalist countries, reaching 24.1 billion dollars by 1980[9]. Despite this, the Polish economy grew in the 1970s, allowing for some relative improvements in living standards. A slight improvement for the working class, however, coincided with a much faster improvement for the privileged bureaucrats. The level of wealth inequality stood at 1:20[10], though this is dwarfed by the inequality which emerged after the reintroduction of capitalism in 1989.

It is the hypocrisy of the party bureaucrats, who claimed to be workers’ representatives, which infuriated the working class. The PZPR bureaucrats had access to exclusive shops, luxurious commodities, and dollars, worth their weight in gold compared to the Polish złoty. At the same time, the working class had to deal with shortages of basic commodities and long bread queues. Their working conditions were also deteriorating, with routine shortages of safety equipment and a long working week, which often included Saturdays. The contradictory nature of this regime did not allow the working class to feel the full effects of the boom of the 1970s, when compared with the party officials.

Furthermore, representatives of western banks had been in regular contact with the Polish authorities, demanding measures which would allow more effective repayment of debts. In April 1980, they tried to persuade the Polish government to remove all food subsidies, and to stop investment in industries such as agricultural machinery, which they deemed unprofitable[11]. The adoption of these measures would have meant austerity and ruin for the Polish masses. But, in any case, action was required in order to pay these debts. The PZPR regime needed to squeeze the living and working conditions of the population even further. It tasked itself with the deletion of the foreign trade deficit, worth up to 1.5 billion dollars. This meant the increase of exports by 25 percent, and the reduction of internal trade by 15 percent, in an attempt to bring equilibrium to their relationship with foreign banks at the expense of Poland’s internal equilibrium[12]. Although working conditions deteriorated and investment stalled, it was the ability to centrally set and fix food prices which was used as a key lever to ramp up austerity.

This economic factor is of tremendous importance. Although the Polish workers rebelled against the PZPR regime, their class interest in better working and living conditions was also directly antagonistic to the interests of the foreign bankers, whose main concern was debt repayments and profits, in the form of interest rates, at the expense of the Polish masses. It is this factor which meant that a return to capitalism on the basis of a mass movement of the working class was impossible.

Underground opposition

In the years preceding the August revolt, the PZPR regime began to feel the ground shake beneath its feet once more. The defeat of the June 1976 strike movement of workers of Radom, Płock and Warsaw’s industrial suburb Ursus, who revolted once again against price increases, inspired the formation of Komitet Obrony Robotników (KOR, Committee for the Defence of Workers).

The KOR was an organisation of the middle class professionals and intelligentsia. Many of its key activists, such as Jacek Kuroń or Karol Modzelewski were ex-PZPR members, who became known for their Open Letter of 1965. This critique analysed the PZPR regime as bureaucratic, and called for the establishment of a multi-party, democratic regime based on workers’ councils[13]. It was clearly influenced by Trotskyism, as the group collaborated with an outspoken Trotskyist, Ludwik Hass, and was in contact with what remained of the Fourth International[14] after Trotsky’s death. It is important to note however, that despite their flirtations and connections with Marxism, none of the KOR intellectuals were genuine Marxists. Their outlooks were defined by their petty-bourgeois backgrounds. Nevertheless, the KOR played an important role in the next few years.

The KOR was a heterogenous organisation, composed of various intellectuals, who fought for the democratic rights of the working class. The KOR attempted to base itself on the industrial working class and published various newspapers, such as Robotnik (The Worker), which alluded directly to Poland’s pre-war Socialist traditions. Politically, KOR was nebulous, united only in its opposition to the PZPR. Antoni Macierewicz stated that KOR was divided between a “secular left” tendency, represented by figures such as Jacek Kuroń and Adam Michnik, and an “apolitical”, “national-independence” wing, led by Macierewicz, who distanced themselves from left-wing politics and, in effect, became a right wing of the movement[15]. Kuroń, on the other hand, anxiously clarified that there was no division at the time, which reveals the conciliatory nature of these ‘secular lefts’, and that the two tendencies, more often than not, agreed on their programme[16].

On balance, KOR was clearly left-leaning. It looked towards the so-called Euro-Communists in the West, for instance approvingly reporting on the conference motion of French Communist-led Trade Union CGT, which supported the right to strike, freedom of speech, and spoke out against repression[17]. Karol Modzelewski’s open letter to the PZPR in 1976, calling for workers’ councils, was shared both to the Italian Communist Party and the Primate [Archbishop] of Poland[18]. The fact that this was shared with these two seemingly opposed parties reflects the confusion of the movement, as well as its conciliationism and the desire for a united opposition to the PZPR on part of Modzelewski. Curiously, the PZPR was furious with Modzelewski’s contact with the Italian Communist Party, not the Church.

The KOR played an important role, despite being dominated by the intelligentsia. It had no more than a few hundred workers in its ranks before August 1980[19]. In a distorted way, the intelligentsia turned the experiences and subconscious grievances of the masses into a political programme. Academic historian Waldemar Potkański recognised that the Trotskyist idea of workers’ control made its way indirectly through the KOR into Solidarność’s demands, not because of the strength of the Trotskyists in Poland (who were almost non-existent), but because of the relevance of their ideas to the needs of workers[20].

Apart from the KOR, the Church also played an important role in opposition to the regime. It tapped into the same mood, but represented different interests. Pope John Paul II’s visit to Poland in 1979 was greeted by millions. The Polish Pope called for human and democratic rights, capturing the imagination of the masses. Importantly, the Stalinists had pandered to the Church establishment throughout the existence of the Polish People’s Republic. In effect, this made the Catholic Church the only semi-legal opposition body which existed outside the PZPR apparatus. Although some rank-and-file priests were genuinely sympathetic to the workers’ cause, the top of the Church apparatus all the way to the Vatican represented a corrupt clique, which wanted a return to capitalism in order to enrich themselves. Their calls for ‘peace’ and ‘love’ were a smokescreen for their interests. The hypocrisy of their slogans have become extremely clear in Poland since the restoration of capitalism. Today, millions of people look at the corrupt, conservative clergy with disgust, rather than with respect.

Ultimately, both clergymen and KOR activists became points of reference for the oppositionist movement. They printed underground material and gave a voice to the working class, which had been completely silenced by the state. KOR and the clergymen were able to achieve this relative popularity because there was no other opposition, and because the working class had not yet entered the scene. It is important to note that, throughout the course of the revolution, both played really damaging roles. They used their authority to apply brakes on the working class movement, limiting its militancy wherever they could.

The masses enter the scene

In any case, the PZPR introduced price rises on 1 July 1980. Having learned from the previous price increases, which caused workers’ revolts of 1956, 1970 and 1976, they hoped that most workers would be away on family holidays and would not act against the increases.

They were wrong. The price increases triggered immediate strike action in the industrial centres of Ursus, Sanok and Tarnów, which fought for and won 10 percent pay rises[21] to partially compensate for the price increases. In Lublin, one victorious strike was followed by another. The walkout of the workers of a communication equipment factory was followed by a HGV factory strike, which in turn was followed by a strike of railway workers, with many other workplaces striking throughout July[22]. One isolated economic strike followed another, reflecting the widespread mood which existed at the time.

Eventually, the strike wave reached the coastal areas, where it turned into a revolution. Due to the pre-existing and organised nature of the local KOR, which had strong connections to the working class, the strike here went further than in other areas. The workers of the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk struck on 14 August, in response to the victimisation and sacking of Anna Walentynowicz, a respected opposition activist and an editor of a KOR journal Robotnik Wybrzeża (The Coastal Worker). Lech Wałęsa, who had also been victimised and sacked from the Shipyard in 1976, jumped the wall into the shipyard and declared an occupation strike. This was a key lesson of the December 1970 strikes, when the workers had instead organised marches, which turned into riots and violent confrontations with the police. The workers wanted to avoid the same crushing outcome. To this end, the Gdańsk workers created a Międzyzakładowy Komitet Strajkowy (MKS, Interfactory Strike Committee) in the shipyard itself. This played the role of a workers’ council. It was a soviet in all but name.

The workers of Szczecin soon followed the Gdańsk workers, with an MKS forming in the Warski Shipyard, led by Marian Jurczyk. Though often overshadowed by the legendary Gdańsk, Szczecin was essential to this movement. The MKSs of cities like Bydgoszcz, Świnoujście, Wałbrzych or Wrocław organised regionally with the Szczecin MKS. In a matter of days, the shipyard workers had won significant pay rises, which inspired other workers to walk out. Significantly, even after achieving their aims, the shipyard workers remained on strike in solidarity with their comrades.

General strikes broke out in one city after another, and the shipyards of Gdańsk and Szczecin transformed into headquarters of city-wide MKSs. In these cities, the real power was in the hands of the working class. The demand for ‘Free Trade Unions’, independent from the official unions and the party (which were nothing more than tools of the bureaucratic apparatus), inspired millions. It is this bold demand which turned the strike wave into a revolution. In the words of the Gdańsk MKS, “we have become the true representative of working people in this country… We want to return to work, but only as full-fledged citizens, and real co-masters of our workplaces”[23]. It is clear that the masses were prepared to accept some hardship, but not when deprived of any decision-making powers and a real input in the fate of their country.

Within days, hundreds of workplaces joined MKSs within these cities, with dozens of delegates joining from other local towns and cities. MKSs had soon formed in other parts of Poland, such as Katowice, and the mining areas of Jastrzębie-Zdrój and Dąbrowa Górnicza, which were also strongholds of the pre-war Communist Party. In spite of the government’s attempts to negotiate with all workplaces separately, the movement retained a strong level of centralised discipline, as workplaces subordinated themselves to the MKSs.

The contradictory way in which rapidly changing class consciousness was reflected on the movement is best represented by the various demands and slogans adopted by the workers at the time. On the surface, there was a significant religious and patriotic theme. Much bourgeois historiography presents these as decisive, and sees the class aspect as an afterthought. In truth, any religious elements in this movement arose as a result of a complete political bankruptcy of the Stalinists, and the aforementioned role of clergymen in the underground opposition. The Church’s ideas of peace, and a nonviolent, benevolent approach towards other human beings were seen as a preferable alternative to the crude, repressive machine of the PZPR. The religiousness of the workers was a reflection of their desire to live in a better society, similar to the religiousness of the Levellers and Diggers of the English revolution, or the religiousness of some workers during the Latin American revolutions of the 20th century.

While for the working class, religious ideas represented an honest desire for a better life, they meant something much different for the Church, which had its own interests. Most of the high-ranking clergy, including the Vatican establishment, were more concerned with preserving the status quo: their cosy relations with the Stalinist regime and their privileges. They therefore opposed the use of religious symbols and flags in factories and MKSs[24]. Cardinal Wyszyński, a leading figure in the Polish Church, was anxious about the influence of the ‘secular left-wing’ in the KOR. They were also anxious about the ‘inflated’ pay demands.

At the height of the strike movement, on 26 August, Wyszyński called for “calm, responsibility and work”. In effect, the Church was singing from the same hymn sheet as the PZPR, looking to calm things down and to pour cold water on the workers’ movement which it did not trust.

A section of workers who had looked up to the Church felt betrayed by it after this speech. Some MKSs decided not to reprint Wyszyński’s words in their areas, so as to not undermine the sense of unity with the Church[25]. The Church’s conciliatory and limiting influence continued to play a role throughout the revolution. For instance, in Wyszyński’s Christmas statement, he called for peace to the sick and those forgotten by society, as well as peace to those in power, so that their service would be filled with the “spirit of love, free from violence”[26]. Its aim was clearly a peaceful resolution between the state and the workers’ movement. This idea became dangerous further down the line, when the Church played a role in holding the workers back when it became clear to millions of workers that compromise was impossible.

On the other hand, the strikers’ patriotism was a symbol of their striving for true independence from subjugation by Stalinist Russia. The Polish flag, which was flown by many of the demonstrating workers, was an honest symbol of resistance and independence given the USSR’s precedent of crushing dissent in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, as well as the USSR’s role in reviving the old great Russian chauvinism in order to control the Eastern Bloc. The patriotism was also a legacy of a long history of national oppression in Poland. To the workers, the Polish flag at the time represented a healthy desire for independence, and for a country which they could aspire to have real control over.

This contradictory mood created some unprecedented scenes. The workers organised Holy Masses to be performed outside the Gdańsk Shipyard right under a huge red banner with the adapted slogan ‘Proletarians of all factories, unite!’ Meanwhile, the Szczecin Shipyards were covered with Polish flags, while the meeting place of the MKS was headed with a red banner stating: “Yes to progressive socialism – No to distortions!” The meetings of MKS would begin with workers singing the Polish national anthem and even religious hymns. However, these have to be understood as outer appearances, which were prevalent in the early stages of the revolution. As the revolutionary movement ‘sobered up’, the slogans that were the most repeated and the most relevant were social, economic and political, relating to the struggle of the Polish working class for a healthy workers’ state, or as they called it, a ‘Self-Governing Republic’. This reflected the real motor force of events.

By 29 August, 340 workplaces were part of the Szczecin MKS, and 600 had joined the Gdańsk MKS[27]. Before the demands of the movement were generalised by the MKSs, some factories produced their own, individual sets of demands which represented the wants of their workers. These were similar across the board, reflecting the mass consciousness at the time. Alongside the demands for economic improvements and freedom of speech, religion and trade union organising, workers universally challenged the rule of PZPR bureaucracy. The Lublin railwaymen demanded a “trade union council, representing the interests of working people”, “full transparency of bonuses and promotions” and “equalising the benefits of the workers with those of the police and the army.”[28]

The electrical and automation workers in Gdańsk shipyard demanded “enabling all social layers to participate in formulating a programme of reforms, given the complete lack of faith in the government…”[29] The paintworkers of the Warski Shipyard demanded “unbiased control over white-collar positions, including the liquidation of these positions where they are proven unnecessary”[30], directly challenging the wastefulness of the PZPR bureaucracy. Even the most well-known demands, those of the Gdańsk MKS, included “making public complete information about the social-economic situation” and “enabling all social classes to take part in discussion of the reform programme”[31]. Almost universally, the workers demanded to be allowed genuine input in decision making, both on a factory and national level.

While the workers did not want a wholesale purge of the bureaucrats at this stage (hence the talk about ‘all social classes’, which to them meant the workers and bureaucrats), the true fulfilment of their demands was incompatible with the continued rule of the PZPR bureaucracy. This fact was recognised by an increasing amount of Solidarność’s membership over the next few months. As early as September 1980, Katowice MKS reported on attempts of workers to completely remove management from their positions[32]. Furthermore, the implementation of these demands would have meant a step towards creating a socialist society with democratic workers’ control and planning, the likes of which has not been seen before.

Under the pressure of the strike movement, agreements between the Gdansk, Szczecin and Silesian MKSs and the government to fulfill the workers’ demands were signed on 30 August in Szczecin, 31 August in Gdańsk, 3 September in Jastrzębie-Zdrój and 12 September in Katowice.

The 21 demands of the Gdansk MKS, which became symbolic of the movement, were:

1. Acceptance of free trade unions independent of the Communist Party and of enterprises, in accordance with convention No. 87 of the International Labour Organization concerning the right to form free trade unions.

2. A guarantee of the right to strike and of the security of strikers.

3. Compliance with the constitutional guarantee of freedom of speech, the press and publication, including freedom for independent publishers, and the availability of the mass media to representatives of all faiths.

4. A return of former rights to: 1) People dismissed from work after the 1970 and 1976 strikes. 2) Students expelled because of their views. The release of all political prisoners, among them Edmund Zadrozynski, Jan Kozlowski, and Marek Kozlowski. A halt in repression of the individual because of personal conviction.

5. Availability to the mass media of information about the formation of the Inter-factory Strike Committee and publication of its demands.

6. Bringing the country out of its crisis situation by the following means: a) making public complete information about the social-economic situation. b) enabling all social classes to take part in discussion of the reform programme.

7. Compensation of all workers taking part in the strike for the period of the strike.

8. An increase in the pay of each worker by 2,000 złoty a month.

9. Guaranteed automatic increases in pay on the basis of increases in prices and the decline in real income.

10. A full supply of food products for the domestic market, with exports limited to surpluses.

11. The introduction of food coupons for meat and meat products (until the market stabilizes).

12. The abolition of commercial prices and sales for western currencies in the so-called internal export companies.

13. Selection of management personnel on the basis of qualifications, not party membership, and elimination of privileges for the state police, security service, and party apparatus by equalization of family allowances and elimination of special sales, etc.

14. Reduction in the age for retirement for women to 50 and for men to 55, or (regardless of age) after working for 30 years (for women) or 35 years (for men).

15. Conformity of old-age pensions and annuities with what has actually been paid in.

16. Improvements in the working conditions of the health service.

17. Assurances of a reasonable number of places in day-care centers and kindergartens for the children of working mothers.

18. Paid maternity leave for three years.

19. A decrease in the waiting period for apartments.

20. An increase in the commuter’s allowance to 100 złoty.

21. A day of rest on Saturday. Workers in the brigade system or round-the-clock jobs are to be compensated for the loss of free Saturdays with increased leave or other paid time off.

Workers’ Power

Although the demands underlined the possibilities of what could be achieved, elements of workers’ control and management had also arisen organically throughout the revolution. After all, the real power was in the hands of MKSs. Sales of alcohol were banned by the decision of MKS, a move particularly radical in a country experiencing an epidemic of alcoholism. A scene from Man of Iron, an award-winning film produced during the revolution, shows a Gdańsk hotel worker, who refused to sell any alcohol to a pro-PZPR journalist, quoting orders from their MKS[33].

Straż Robotnicza (Workers’ Guards) were established to keep order in the cities and factories. The memoirs of Genowefa Klamann, an engineer at the time, describes the self-governance of MKS. Workers volunteered to carry out numerous administrative, maintenance and cleaning duties to ensure the effective running of the MKSs, while delegates from factories large and small discussed their business, demands and production plans[34]. Workers were assigned to ensure information reached workplaces across the area[35]. Workers also started their own newspapers and bulletins, as well as organising communication with the MKSs in Szczecin, Katowice and Jastrzębie[36]. Such measures were necessary due to the media blackout and censorship.

Further elements of workers’ power arose as a result of the strike itself. For instance, the oil refinery dispensed fuel only when formally permitted by the MKS. Unlimited permits were granted to essential services, such as ambulances. When farmers complained of a shortage of seals for their tractors, the Gdańsk MKS decided to allow a striking factory in Tczew to produce such seals. Another episode arose when Gdynia workers warned that 30 tonnes of fish would be wasted if no action was taken. In response, the MKS commissioned the canned food factory to preserve the fish, and the tin factory to manufacture the necessary number of tins[37]. This represented planning and production organised by the workers without management or the party.

Indeed, the trade unions took up tasks far beyond the conventional nature of established unions. Tymczasowa Rada Robotnicza (TRR, Temporary Workers’ Council) of ‘NAUTA’ workplace in Gdynia tasked its union with the “material, social and cultural enrichment” of workers and their families, establishing a workers’ democracy and even organising credit and grants for those in need[38]. While fighting for a more democratic workplace, the TRR commissioned its workers with looking for more efficient ways of working, in order to help the economy find its way out of the crisis[39]. The day-to-day running of the representative body of the workers and areas affected by strikes required elements of workers’ control and management, expressed more and more through a regime of workers’ power exercised through the MKSs, providing a glimpse of what was possible if implemented on a wider scale.

These moods also extended to other layers of society, who were strongly affected by the revolution. Andrzej Krawczyk, a representative of taxi drivers in Silesia, said in a letter to the paper of MKS Katowice that his colleagues consider themselves workers, who wish to fight for workers’ control in the common interest[40]. The farmers south of Warsaw refused to sell their products to the government purchasing agency, and were sending food free of charge to the strikers[41]. Further elements of workers’ power arose organically and reactively over the coming months, essentially filling any power vacuums left by the retreat of the PZPR.

The foundation of Solidarność

The period between July and September 1980 was a period of revolutionary upsurge and rapid advancement for the revolution. Through this experience, it represented a leap in the consciousness of the masses. In the words of Szczecin workers, “Our lives are more fulfilled, intense, and in constant rush, attempting to solve the ever emerging needs. We don’t always have time for even a moment of reflection… Let’s take care, to ensure that our new creation matches our dreams.”[42]

The period between October 1980 and November 1981, represented a time when the revolution attempted to consolidate itself and achieve all its aims. Its fate would be decided in this period.

After the signing of the Gdansk agreements in August, the working class began the formation of its long-desired free trade unions. MKSs were turned into Międzyzakładowe Komitety Założycielskie (MKZ, Interfactory Founding Committees) and Międzyzakładowe Komisje Robotnicze (MKR, Interfactory Workers’ Commissions). The concessions that the movement had won in the August Agreements had shown workers across the country that this was different to the uprisings of 1970 or 1976. Following the lead of Gdańsk, Szczecin and Silesian workers, MKZs formed in other important cities, such as Łódź on 5 September, Poznań on 11 September and Kraków on 15 September[43].

In practice, the MKZs and MKRs had become transitional bodies between MKSs and branches of the future NSZZ Solidarność. Their task was to prepare the ground for the arrival of free trade unions. NSZZ Solidarność was eventually founded by MKZ and MKR delegates from across the country on 17 September in Gdańsk. It is worth noting that 17 September is a key date in Poland; it is the anniversary of the USSR’s invasion of Poland, which was carried out in alliance with Nazi Germany in 1939 through the aforementioned Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. This reflects the tremendous courage and confidence of workers at the time – the experience of Hungary and Czechoslovakia was still fresh in everyone’s memories.

The founding meeting also formed Krajowa Komisja Porozumiewawcza (KKP, National Coordinating Commission) to coordinate the work on a regional and national level, and negotiate with the government.

The process of absorption of MKSs into Solidarność confirms the aforementioned observation, that the union had gone much further than a conventional trade union, which usually involve minimal engagement from the workers and top-down decision making. Born on the basis of workers’ councils and the mass movement of workers, the union itself had become an organ of workers’ power. It would go on to attempt a deep-reaching reform of the Polish state, which was only possible through workers’ power.

This period also saw the beginning of political developments within the movement. In the words of Wałęsa in November 1980, “we will definitely not return to capitalism, and copy any of the western models, because this is Poland and we want Polish solutions. Socialism is fine, and let it be, we just need to control it.”[44] Numerous honest non-Marxist historians of the period, such as Jan Skórzyński, note that capitalism was not trusted across the board at the time[45]. Many still remembered the fate of workers and peasants under the interwar Sanacja dictatorship, who were consigned to slums and huts, in conditions of harsh poverty.

Lech Wałęsa, a former electrician at the Gdańsk Shipyard, was a leading figure of the movement. His popularity in that period came from his ability to become a conveyor belt of ideas coming from the general consciousness of the working class onto the national stage.

However, while his working class credentials and a straight-to-the-point talking style gave him popularity, he represented the conciliatory, moderate and confused wing of the movement, who would later go on to lead it to a crushing defeat.

In reality, socialism had been devalued as a word to an extent, as it meant different things to PZPR officials, Solidarność leaders and rank and file workers. What’s clear is that there was a mass mood in favour of direct workers’ control and democracy, and a lack of any demands for free markets or capitalism. It is this fact that demonstrates that for all the contradictory confusion, religious and patriotic connotations, Solidarność fought for ‘workers’ self-governance’ and a ‘self-governing republic’, which became the key slogans of the movement above all others. This represented a movement towards the conquest of power by the working class based on the democratic control and management of the planned economy, not capitalism.

The next months presented challenge after challenge. In October and November, there was an attempt to register Solidarność, which was met with pushback from the state. Important battles emerged around the attempts to create unions for non-workers, such as the students’ formation of Niezależny Związek Studencki (NZS, Independent Students’ Union) or NSZZ Rolników Indywidualnych “Solidarność” (Individual Farmers’ Independent Trade Union “Solidarność”). Even Civil Servants and the officers of Milicja Obywatelska (MO, Citizens’ Militia) attempted to unionise under Solidarność. Likewise, the Army was completely unreliable as a tool to suppress the revolution, as many rank and file soldiers supported the workers. The state was powerless. Localised general strikes were on the order of the day, as workers attempted to improve their conditions and settle scores with the bureaucracy.

The Solidarność radicals

The radical mood grew as a result of the objective situation. In the following months, Poland continued to experience social and economic earthquakes. The first six months of 1981 saw a 15 percent increase in the cost of living. Food price increases were announced in April, and July saw a 20 percent cut in meat rations[46], which sparked spontaneous hunger marches in the summer and provoked open splits within the PZPR[47]. All these events produced conflicting views and tendencies among the working class. While the conciliatory tendency led by Lech Wałęsa and other former KOR activists based itself on unity and collaboration with the government, the radicals continued to grow in influence.

The radical tendency was relatively unorganised and for a long time lacked a national point of reference. Its main expressions were outbursts of anger and pressure from below. It grew from the indignation of workers active in the movement, whose uncompromising attitudes and class instincts tapped into the mood on the shop floor. Already, by February 1981, the workers in Bielsko-Biała had organised a general strike, demanding the removal of local bureaucrats. A student strike was organised in Łódź, demanding the formal recognition of the Independent Students’ Union (NZS). Peasant strikes erupted in Rzeszów, followed by workers’ strikes in Białystok, Olsztyn and Wrocław. All of these battles occurred without the approval or prior knowledge of the National Coordinating Commission (KKP), forcing Wałęsa to play the role of a firefighter, going from one area to another to calm things down, acting as a brake on the movement.

Despite the spontaneous, unorganised character of this mood, in some areas the radicals did organise on a local level and proved to be far more popular than the petty-bourgeois KOR activists. The radicals also exerted significant influence by the virtue of their methods, which were bold and clearly aimed at winning over the working class.

In Szczecin, 320 thousand leaflets were printed by the local Solidarność with a statement openly authored by a worker activist, Michał Kawecki. These were distributed boldly and postered on trams and in taxis. The leaflets stated that Solidarność is a movement opposed by those who were in power, and whose privileged lives were lived at the expense of the poorer part of society. “Our movement is a class movement, it brings hope to millions of people in its perspective of removing the privileges of a few hundred thousand people tied to the state and Party apparatus”[48].

The Bydgoszcz crisis

Apart from innumerable strikes and incidents over local issues, a key event unfolded in Bydgoszcz in March 1981. When Farmers’ Solidarność activists occupied a building in an attempt to fight for recognition of the Farmers’ Solidarność, they were confronted by the police (MO). As pressures grew, one of the Solidarność activists shouted at the officers, saying they resembled the Spanish police, and that they aren’t supposed to be like a “western police officer, beating people up on the order of the bourgeoisie!” Following a confrontation, three of the Solidarność activists were seriously injured and hospitalised, which provoked a huge wave of anger against the government.

The demand for a general strike grew, but Wałęsa was in no mood for it. He had just pacified the demand for a regional general strike in Radom, and furiously walked out when others in the KKP suggested an immediate general strike. The mood was intense, though the KKP eventually acceded to Wałęsa who used all his personal authority to push back against a general strike. The KKP agreed to call for a 4 hour general strike on 27 March, as a warning and a precursor to a national general strike on 31 March.

The 4 hour strike was a huge show of strength on behalf of the working class. It started with blasts of sirens from factories and other workplaces, bringing the country to a complete standstill. Millions of workers struck for 4 hours, displaying enormous discipline and strength of feeling. Workers’ Guards were patrolling the factories and shipyards. Every single city, town and village was involved. Even TV stations did not transmit the usual programmes, and instead displayed a message: “On strike – Solidarity.” The 4 hour strike showed huge support among the masses, and a “mood of uprising”[49]. Karol Modzelewski, one of the Solidarność leaders stated retrospectively that “we almost physically felt the determination of the mass of workers…” [50] The depth of the March 1981 strike rivals that of revolutionary general strikes such as in Barcelona in 1936 or in Paris in 1968. In that moment, the working class in Poland stood on the brink of power. All it would have taken was for the leadership of the KKP to give the word.

The Soviet Union’s General Secretary, Brezhnev, was furious at the Polish First Secretary Stanisław Kania. He shouted at him over the phone and demanded PZPR lead a military crackdown against Solidarność. Brezhnev knew that a direct military intervention could become problematic, as the Soviet Army was increasingly engaged in Afghanistan. In fact, military intervention by the USSR was extremely unlikely at this stage, as the situation in the USSR was that of growing crisis, unlike during its previous interventions in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. If an invasion did occur, an internationalist, working class appeal would have been able to win over the invading troops, sons of workers, to the cause of political revolution. Brezhnev, Honecker and other bureaucrats knew this very well, and they were terrified of this prospect.

It was now or never. According to one Solidarność survey in Płock, there was 79 percent support for a national general strike[51]. This was without a doubt even higher in the key industrial centres such as Gdańsk, Szczecin, Łódź and Warsaw. With the right leadership, Solidarność could have taken power at that time. But Wałęsa did not want to take it. Most of Wałęsa’s advisors, including Kuroń and Wyszyński worked overtime to call off the 31 March strike. Even Pope John Paul II, who was a strong influence on Wałęsa, was a part of this effort, as evident in his letter to Wyszyński in March 1981[52]. Ultimately, the national general strike was called off on the eve[53]. KOR leaders, such as Andrzej Gwiazda, supported this decision. The decision, however, was met with disappointment on the part of rank-and-file activists who raised concerns about the accountability of the KKP. The Bydgoszcz crisis was a turning point, where the idea of Solidarność’s unity was crushed. The union’s leadership was beginning to be seen as out of step with the desires of the masses. In the words of Lech Dymarski, a member of the KKP, “The government’s back is against the wall, but so is ours. Our wall is the working class…”[54] This increasingly radical mood provided a huge impetus for the grassroots militants of Solidarność.

Regional Solidarność elections

In June 1981 Solidarność organised elections to its local bodies. Although many candidates stood on personal credentials, the most popular candidates were those who demanded no compromise with the authorities. In Szczecin, one of the most applauded speeches was a radical religious contribution by the history teacher, Łuczko: “Christ said that those who reach for the plough and then look back, are not worthy of Heaven. We do not have any other way.” On the other hand, steelworker Banaś called for a new workers’ party to represent Solidarność in government and have a meaningful impact on decision making. A pro-Wałęsa candidate, Dr Zdanowicz received the least applause[55]. One Shipyard worker Tadeusz Lichota stated that his inspiration was Lenin – “but the real one”, not the Stalinist caricature.

Lichota, alongside Edmund Bałuka, the legendary workers’ leader of December 1970, attempted to form a new party called Polska Socjalistyczna Partia Pracy (PSPP, Polish Socialist Labour Party), with its base in the Szczecin Shipyard, but also with branches in other cities. The PSPP had a positive programme of revolutionary measures and policies necessary to fight for a healthy workers’ state. Although it gained popularity in the few areas where its members were present, the party was formed too late, and was unable to play any decisive role in the events.

Another example of the potential that existed flared up in Jastrzębie, where Stefan Pałka, a worker influenced by Trotskyists and a vice-leader of Solidarność in this Silesian mining region formed a revolutionary cell, which published Walka Klas (Class Struggle), a bimonthly Marxist newspaper, with a circulation of 1000. These isolated successes of Marxist workers highlight how the workers were open to revolutionary ideas. But they also show that a revolutionary party cannot be improvised, and that its core has to be built before the revolutionary events start. If such an organisation existed before 1980, it would have been able to win over the Polish working class in 1981, when the illusions in Wałęsa and his supporters started to fade away.

Another example of the strength of radicals among the rank-and-file comes from Łódź, an important industrial city, where these radicals formed the so-called ‘independent’ group, led by textile workers Mieczysław Malczyk and Zbigniew Kowalewski. The independents stood in direct opposition to the established leadership. They criticised the ‘political’ influence of the KOR on Solidarność, noting that the KOR was using the official papers of Solidarność to push its own agenda. The group also feared that workers would get used and sidelined by people with their own ambitions. It is worth quoting their programme in some length:

“On the basis of the social revolution, initiated in August by the working class… will rise a truly humane Socialism, based on satisfying the material and spiritual needs of the people… This revolution puts to an end the rule of a bureaucratic apparatus and its monopoly over the means of production… The historical task of Solidarność… depends on the victory of a moral and social revolution, and the realisation of true Socialism…”[56].

This group swept the board in the June elections, outnumbering the pro-KOR group. These scenarios were replicated in almost every part of the country.

Though the radicals continued to lack a national organisation and a national point of reference, they eventually made their presence known at the First Congress of Solidarność, in September 1981, where they went far beyond Wałęsa’s conciliationism. Although they had no ideas in common – their ideas ranged from religious radicalism to Marxism – it was their uncompromising attitude and the demand for real workers’ power and a confrontation with the ruling party that ultimately gave them support of the local workers. This confirms the real mood on the ground, which was far more militant than the one represented by Lech Wałęsa, the Church, and the petty-bourgeois advisors.

Ferment in the PZPR

Although there were many local outbursts and battles throughout 1981, the national congresses organised by Solidarność and PZPR also became key battlegrounds, as both organisations faced revolts from radical grassroots members. Both of these radical movements were led by the working class. The PZPR held its congress in July, while Solidarność commenced its first congress in September. What happened in the course of these congresses shows that after a long period of strikes, the working class was looking to define itself politically.

The July PZPR Congress was seen as an opportunity to reform the Party, and purge it of the bureaucrats who had brought the country to social and economic ruin. Although the congress was observed by many workers around the country, the distrust towards the Party was so overwhelming that the reformers had had to act in relative isolation. The reformers in the PZPR had become a sideshow to the movement, rather than a proper part of it. The PZPR had become totally bankrupt in the eyes of the masses, who wanted nothing to do with it.

There was a layer of workers who formed a rank-and-file of PZPR . However they were usually the better paid layers, such as engineers and white collar workers, who became party members as a way of boosting their careers. The lower ranks of party and state bureaucracy, whose living conditions were not so distant from the conditions of the working class, were also impacted by the developing revolutionary crisis. Nevertheless, these layers tended to sympathise with Solidarność, and even participate in it directly. A layer of members of PZPR and the unions aligned with it were also veterans of the struggles of 1970 and 1976, who turned to the only legal organisations in attempts to fight for their class. These layers of the PZPR fuelled the ferment in the Party and the internal discontent against the top Party apparatchiks.

The PZPR rank-and-file opposition emerged in the town of Toruń and became known to the bureaucrats as the ‘Toruń disease’. Zofia Grzyb, a worker from Radom and member of the PZPR’s politburo, also became a symbol of transformation within PZPR[57]. The oppositionists represented a belief that if Solidarność was to control the economy, the party needed to be transformed as well. In effect, these people attempted to turn the PZPR into a genuine, democratic working class party. Internally, they called for ‘Socialism of worker self-governance’.

One PZPR meeting of shipyard workers in Szczecin in February 1981 saw intense anger against the party officials.

“Comrade Kania says that the party should not participate in the strikes… But the party comes from the working class… They talk about anti-Socialist forces in Solidarność, but don’t they come from the party? From those who ruined this country?”

Another voice speaks:

“There is so much injustice, let’s make things straight! Why can’t workers be in charge of PZPR Committees?”

Every contribution attacked the leadership, and was met by giant applause[58]. A similar meeting took place between the First Secretary Stanisław Kania and PZPR members in Gdańsk, who demanded the party properly represent its 3 million members[59]. Such meetings were replicated across the country.

Despite their relatively spontaneous character, the mood was widespread among the party’s working class membership, and represented genuine danger to the hardcore bureaucratic establishment within the party. Where possible, the rank and file managed to replace their leaders. In Bydgoszcz, 322 out of 393 party officials were replaced, though the national structures of PZPR made the fight for a genuine, viable opposition an uphill struggle. Many worker oppositionists were expelled from the party. This included activists such as Zbigniew Iwanow, a leading figure of the ‘Toruń disease’ who attempted to create a ‘level structure’, i.e. to introduce democracy to the party’s centralism.

The July Congress of PZPR reflected this political struggle on a national basis, but due to the anti-democratic nature of the Party, the reformers were ultimately in a minority at the Congress – 20 percent of PZPR delegates to the July Congress were also members of Solidarność[60]. Although they staged a fight, the oppositionists suffered a defeat and failed to transform the Party. Following purges, demoralisation and resignation, this marked the end of opposition within PZPR. Some oppositionist figures such as Albin Siwak, a loose cannon and an anti-semite, were allowed to remain in the spotlight, in effect putting people off the PZPR and dispelling any hopes of transforming it even further[61]. In any case, the attempt to reform the party represented the far-reaching effects of the revolution, its working class character, as well as the impossibility of reforming the bureaucratically degenerated PZPR.

After the bureaucrats had succeeded in retaining their control over the PZPR, they regrouped and regained their confidence. They doubled down in opposing Solidarność in the coming months, preparing politically for martial law. During the negotiations between PZPR and KKP in August, the government broke off the talks as soon as they started talking about “Union control over production and distribution of food”, “the self-governance and independence of workplaces” and their “access to means of mass communication”[62]. The union leaders were forced to adopt these demands in response to the growing radicalisation from below[63]. The PZPR correctly saw this as a challenge to its power. The party broke up the talks and falsely blamed Solidarność. Deputy Prime Minister Mieczysław Rakowski went on the offensive, making demands on Solidarność to fall into line. This included furious attacks in the media. The workers responded by refusing to produce and distribute official newspapers, and only promoting workers’ newspapers and bulletins.

First Congress of Solidarność

The period from September to December 1981 represented a final chance for Solidarność to recover from the downward ‘slippery slope’ it found itself on following the Bydgoszcz crisis. By now, the official leadership of Solidarność was routinely losing control over the rank and file, and were doing all they could to hold the movement back. On the other hand, the PZPR had evolved following the party congress and became less willing to accept compromise. The PZPR made its first plans for martial law in December 1980, but it was in Summer 1981 that they seriously started to consider it.

Wałęsa stated that:

“It was clear that they were preparing arguments, and exhausting the nation. All these strikes, shortages, impatience. It was the beginning of the end. They were just waiting for the right moment…”[64]

Rather than seeing this “impatience” from below as an opportunity to carry out the fight until the end, Wałęsa despaired about it. The PZPR officials discussed the plans for martial law with Moscow on 25-26 August, including the names of those workers that they planned to jail immediately. By 18 September they had commenced operation ‘Sasanka’, instructing local authorities and MO about practical plans for the implementation of martial law[65]. The CIA knew about the plans for martial law, as it withdrew one of its top informants, Ryszard Kukliński, from the country. However they took no further action because they knew this would have caused another ‘Bydgoszcz Crisis’, except this time the moderates would have had even less political authority to hold the movement back. Despite their moral posturing long after the movement’s defeat, the reality was that the western capitalists preferred to collaborate with PZPR to restore stability and Poland’s ability to repay its debts, even if it meant a brutal defeat for the Solidarność movement. In any case, the month of August 1981 proved the impossibility of a peaceful co-existence between a free trade union and the PZPR, as polarisation intensified on both sides.

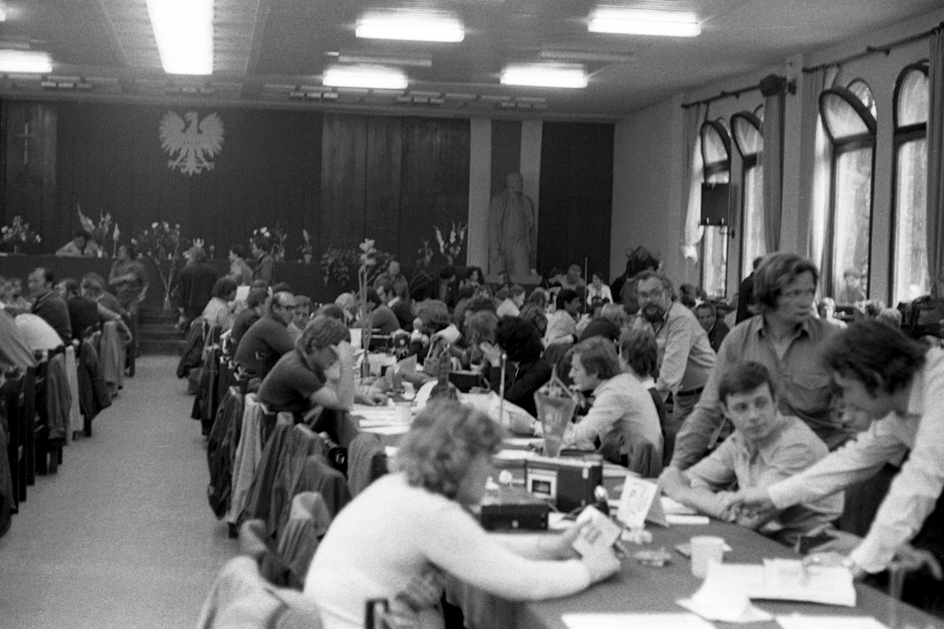

The First Congress of Solidarność was an opportunity to turn things around. It took place in Gdańsk in two parts. Its first part took place on 5-10 of September, and its second part between 26 September and 7 October. The congress was a tremendously democratic affair. The turnout for the union’s elections was reported to be 93.98 percent, or 8,906,765 out of 9,476,584 members. It was dominated by the youth, with 88 percent of delegates under 45[66]. If an intellectual tried to ‘talk a lot without saying much’, the delegates would vote to end their contribution. On the other hand, if a popular speaker ran out of time, the delegates would vote to extend their allocation[67]. The congress was fundamentally radical, and the strength of feeling was such that the official chair’s Jerzy Buzek’s role was somewhat symbolic, and the real power in the meeting was among the delegates. The congress decided not to allow journalists of TVP to report on the proceedings. In the words of Krzysztof Wolicki, a pro-opposition journalist, they were not let in “for the same reason you don’t let an armed gangster in on a plane.”[68] The union had friendlier relations with the TV station PKF, whose staff were more sympathetic to Solidarność.

Many of the local leaders were strongly influenced by the rank and file.

“Whereas Szczecin union leader Marian Jurczyk demanded free elections to the Sejm, Andrzej Gwiazda of Gdańsk exhorted workers to take greater control in the workplace, and Bydgoszcz leader Jan Rulewski mocked and challenged the Warsaw Pact itself, Wałęsa began his election speech by urging respect for the state authorities.”[69]

The congress was met with fury by the bureaucrats. The Soviet TV station TASS felt it was necessary to proclaim several lies about the Congress to undermine its legitimacy as a voice of the Polish working class, for instance that 89 percent of delegates were full time employees of the union. In truth, 48.2 percent of the delegates were blue collar workers, 32.8 percent were ‘educated workers’ (white collar workers, engineers, etc.) and 14.4 percent were farmers[70]. In September and October, the union saw a flurry of attacks from the official media, with Pravda calling the union’s congress an “orgy of anti-Socialism and anti-Sovietism”[71] and the Polish Trybuna Ludu attacking its radical motions.

In response, one delegate, Edward Lipiński, gave a speech responding to the attacks,

“I was mortified recently, when I heard from General Jaruzelski that he is ready to mobilise the army to defend Socialism in Poland… How is Socialism in Poland threatened? What do you mean by anti-revolutionary and anti-Socialist forces?… It is THEIR ‘Socialism’ that is anti-revolutionary and anti-Socialist (huge applause, shouting).”[72]

The hostile media propaganda reflects the nervousness of so-called Communist bureaucracies in other countries that the movement could spread beyond Poland’s borders.

Indeed, among other motions passed during the congress, an internationalist motion was adopted, called “Appeal of the First Congress of Delegates to workers in Eastern Europe”. Many workers of Solidarność were becoming more and more conscious that there was no way out on the basis of successfully transforming a single country. In the words of Marian Jurczyk, “I believe that the banners of Solidarność will be triumphant from the Ocean to the Urals”[73].

This internationalist motion flew in the face of the lies peddled by the governments of the USSR and other pro-Soviet countries. Solidarność’s appeal clarified its mass, working class character and the ‘deep felt’ commonwealth with the workers of Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, East Germany and other countries[74]. This was further clarified by an unnamed delegate, who stated that “The tradition of our union is appealing to people, societies, and not to the lords and the wealth of this world”[75]. This was met with thundering applause, and it reaffirms the Polish workers’ internationalism towards the workers of the West as well as the East. Although it was impossible to invite delegations from other pro-Soviet countries, a few dozen trade unionists were present, including from the USA, Japan and Western Europe.

Wałęsa and others were against this internationalist motion. Jacek Kuroń, one of the KORist intellectuals, ran around the Congress hall in panic in an attempt to stop the vote[76]. Ultimately, the motion was overwhelmingly carried.

Another radical motion adopted was the programme of the union itself. It blamed PZPR’s mismanagement for the economic crisis; demanded “authentic worker self-governance”, which would mean making the workers genuine masters of their workplaces, organised on a regional and national level, through free elections; as well as calling for the democratic transformation of the existing state apparatus, including the judiciary and the security services, under the control of the workers’ self-governing councils[77].

More criticism arose regarding Wałęsa’s style of leadership and the handling of the Bydgoszcz crisis. Nonetheless, Wałęsa was ultimately re-elected with 55.2 percent of the vote, with the rest split across Marian Jurczyk (24.1 percent), Andrzej Gwiazda (8.84 percent) and Jan Rulewski (6.21 percent). This reflected the fear of Soviet intervention and a desire for unity, but also the weakness of the radical opposition in being able to put forward a clear alternative to Wałęsa. In any case, all these facts highlight the radical, working class nature of the congress. After decades of censorship and a lack of ability to organise independently, the consciousness of workers had caught up rapidly. The congress once again confirms not only the widespread desire for a ‘self-governing’ republic with workers’ control, but also its internationalist aspirations.

After the congress

Wałęsa’s lack of control over the congress was anything but reassuring to the PZPR, who began to view the movement with complete mistrust. By the end of the congress, the government refused to continue its negotiations with Solidarność. On one hand, there was a growing mood of anger from below. Numerous isolated occupation strikes occurred in October and November, including among the miners. The union also began preparing the ground for a ‘National Federation of Self-Governing Councils’[78], a clear step towards preparing for workers’ self-governance. Some areas, like heavily industrial Żyrardów near Warsaw, were facing severe food shortages, provoking a town-wide general strike.

On the other hand, Solidarność’s leaders were no longer the most accurate reflection of the movement. At the same time as the working class was leading radical struggles on a local level, the movement’s tops had a completely different attitude. In a November meeting between Wałęsa, Cardinal Glemp and General Wojciech Jaruzelski, Wałęsa attempted to appease Jaruzelski, to no effect. Cardinal Glemp “did not say anything”[79]. The government was able to sense the weakness of the union’s leadership, and the isolated character of the strikes and occupations that were taking place. Although the conditions were ripe for the emergence of a new leadership, more radical than Wałęsa and which would be able to lead the movement in the direction of a self-governing workers’ democracy, the doors were also beginning to open for the introduction of martial law.

Martial law

After several attempts to ‘test the waters’, such as the pacification of an occupation strike of firefighters in Warsaw on 2 December, martial law was ultimately introduced on 13 December 1981. The measure was a result of a prolonged stalemate between Solidarność and PZPR, and overwhelming pressure from the USSR to resolve the situation. In effect, the imposition of martial law was a military coup, carried out with the approval of PZPR. General Wojciech Jaruzelski announced the de facto takeover of power by Wojskowa Rada Ocalenia Narodowego (WRON, Military Council of National Salvation).

Martial law was possible for many reasons. A key one of these was the failure of the workers’ leadership. The working class was ready to fight until the end, which would have meant a final reckoning with PZPR and the coming to power of the organised working class. The Solidarność rank-and-filers had gone beyond the hopeless manoeuvres of Wałęsa, Kuroń, Glemp and others, who did not want to fight. However they had not yet managed to express themselves through a new national leadership with clear socialist ideas for reclaiming the planned economy by the workers. Such an alternative cannot come out of the blue. That this perspective was not clearly raised was a direct consequence of the lack of a revolutionary party built prior to the revolutionary events.

This situation resulted in a relative atomisation of the movement towards late 1981. After such a long period of struggle, there was a rising feeling amongst the bureaucrats and the more politically backward layers of society that order needed to be restored. To circle back to the words of Ted Grant and the British Trotskyists at the time, there was no halfway solution. The PZPR clearly saw the danger of the radicals taking power, as evidenced by the references to the attacks of “extremists” and “elements undermining the Polish Socialist State” in Jaruzelski’s television address[80]. The introduction of martial law was met with rage on part of the working class, and a wave of occupation strikes broke out in many key industries, including the Gdańsk and Szczecin Shipyards, with a new National Strike Committee being formed.

Unfortunately, these movements were crushed by the state. Zmotoryzowane Oddziały Milicji Obywatelskiej (ZOMO, Motorised Divisions of Citizens’ Militia) and the Army were sent to crush any resistance. Although the lower ranking officers and soldiers were sympathetic to Solidarność in the beginning, after 16 months of impasse, the party was able to use the fear of Soviet intervention and the demand for order to use troops to crush the workers. This included night-time raids on the occupied factories in Szczecin and Kraków, supported by tanks, and the brutal suppression of miners in Silesia, where the police force fatally shot numerous workers[81].

In some areas, the workers were able to talk sense into the soldiers, who then refused to attack the workers. But these were isolated incidents[82]. The state used its armed bodies of men to crush factory after factory, with the final occupation being crushed at the ‘Piast’ coal mine on 28 December. Martial law dealt a fatal blow against the revolution. Around five thousand Union members – the cadre core of Solidarność – were interned and imprisoned in December 1981, with many thousands more over the following years[83]. A 1989 government commission estimated that about 90 were murdered by the state apparatus during the period of martial law. Many more deaths remain unexplained[84].

Conclusion

Despite its tragic end, the Solidarność movement from August 1980 to December 1981 was the most tremendous revolutionary movement in Polish history, and one of the most important revolutions of the 20th century. The historical purpose of this movement was to carry out a purge of the state and the bureaucracy through a political revolution, and a deep reform of the planned economy in the interests of the working class. In spite of its failure, it was the most advanced movement for a healthy workers’ state in the history of Stalinism. If successful, this revolutionary movement would have spread internationally. A genuine workers’ government in Poland would have attracted workers not only in degenerated workers’ states, but also in the West.

Following martial law, the original Solidarność was gone. It had been transformed by the underground conditions and the deprivation of its mass base into a completely different organisation. Although some local outbursts occurred in the 1980s, including strikes and takeovers of official May Day rallies, they were usually carried out as local initiatives, and the movement’s overall character started to change dramatically. The dramatic defeat severed the connection between the leadership and the mass of the working class. The most opportunistic, out of touch and even openly right-wing elements gained more prominence. What was left of Solidarność was funded no longer by the workers, but by foreign state bodies such as the CIA, who donated large amounts of money to these opportunists from late 1982 onwards[85]. At this stage, Solidarność became a tool in the hands of the imperialist West in fighting for capitalist restoration. Ultimately, the so-called communists of PZPR, hand in hand with the degenerated Solidarność, re-established a free market economy after 1989. This was accepted by all the main leaders of Solidarność. By then, the working class was mostly crushed and forced out of activity and political life. The Minister of Finance, Leszek Balcerowicz, carried out the dictates of the western bankers and imposed shock therapy. He and the forces of capitalist restoration were trying to make the Polish working class pay for decades of mismanagement by the bureaucrats. After 1989, Solidarność played an even more pitiful role, openly collaborating with the bosses and the most degenerate right-wing elements. It gave up the fight for its original demands from August 1980, which were incompatible with the transition to capitalism. It completely haemorrhaged its membership. The defeat of the Polish working class in 1981 was a key factor which allowed the Stalinists in USSR and Eastern Europe to restore capitalism later down the line. The workers of Eastern Europe thought: if Solidarność went so far and it still lost, then what’s the point in fighting back?

With the exception of the general strikes of Romanian workers in 1989 – who demanded the removal of the particularly ruthless Stalinist dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu and an improvement in living conditions – as well as some limited, defensive strikes in certain areas, the restoration of capitalism was met with relative passivity. What followed in the 1990s and 2000s in particular represented a ‘great depression’ in Eastern Europe. The scale of the collapse of the productive forces and living standards is comparable only to wartime scenarios. Millions of lives have been deeply scarred by this transformation. Countless others were cut short.

Nevertheless, the revolutionary, 16-month long upsurge of workers’ power that gave life to Solidarność is tremendously rich in lessons and experiences, and proves that the working class is capable of showing a way forward even in the most unfavourable and grim of circumstances. The key lesson, however, is that it needs a leadership, a revolutionary party sufficiently rooted in the working class and armed with the ideas of genuine Marxism and workers’ democracy, which is able to help it play the role of transforming society.

The banner of Solidarność has long ago been blackened by careerists and right-wing traitors to our class. Wałęsa himself lives a life far exceeding in luxury to the one experienced by PZPR bureaucrats, occasionally opening his mouth to call on striking miners to be “beaten up” by the police, spout something reactionary about homosexuals, or lament about the ongoing demise of the liberal world order. Unlike the workers of the revolution, Wałęsa and all the other ladies and gentlemen at the top have certainly done well for themselves after 1989.