Comrades of the Revolutionary Communist International (RCI) from various states of Brazil gathered in São Paulo for an emergency congress. Its purpose was to found a new Brazilian section of the International and to hold a cadre school. Dozens of delegates, who had been previously elected in regional plenary sessions, took part in the proceedings from 20 to 23 November, beginning a new phase in the history of the RCI in Brazil.

[This report can also be read in Portuguese]

The event took place two months after the majority of the former Brazilian section’s leadership broke with the RCI. With only two months to go before the congress, an undeclared faction crystallised around leading member Serge Goulart, which opted for a unilateral and hasty split. The immediate reason was the prospect of losing the congress to the minority ‘Faction in Defence of the International’, which was gaining strength from the rank and file of the organisation, especially among the youth.

Those comrades who refused to embark on the sectarian adventure of the majority of the leadership of the International Communist Organisation (OCI) responded to the call of the International Secretariat of the RCI and held an emergency conference on 21 September. At this conference, they called for a congress to found a new section of the International in Brazil, to bring together supporters of the RCI from across the country, and to debate the ideas they defended.

A new beginning

The decision taken by the delegates at the congress on the name of the new organisation, Internacional Comunista Revolucionária (Brasil) (RCI Brazil), is a highly symbolic gesture. This unique choice reflects the desire of the Brazilian comrades to establish a true Brazilian section of the International. It expresses confidence in the ideas and traditions of the RCI as those capable of overcoming the difficulties of the past and paving the way for the future.

The majority of the OCI leadership resisted assimilating the ideas and traditions of the RCI, despite the fact that, since 2008, what was formerly the ‘Marxist Left’ had formally been a part of the International. Over time, disagreements arose, especially over the character of Chinese capitalism and the possibility of developing the productive forces under capitalism.

Some of these differences were expressed in August this year at the RCI World Congress. Serge Goulart’s undeclared faction presented a counter-report to the congress, which opposed the world perspectives document with their own. However, their perspectives document did not obtain a single vote from any delegate or member of any of the other sections and groups of the International, which is present in more than 60 countries.

In addition, some of the leaders of the Brazilian section were convinced by the ideas and analysis of the International and decided to open a debate in the Brazilian section to correct the perspectives that had been developed. A factional struggle ensued, and Serge’s undeclared faction, faced with the prospect of losing the national congress convened for November, put forward a plan to break with the RCI.

It became clear that Serge Goulart’s secret faction never broke with the legacy and traditions of so-called ‘Lambertism’ from which they had come. Serge and other former cadres of the section were educated and trained by Corrente O Trabalho, a tendency which operated within the Brazilian Workers’ Party, and were members of the so-called ‘Trotskyist’ international of Pierre Lambert, a French Trotskyist leader. From that period, they brought with them Zinovievist conceptions of theory, party building, and methods – based on resolving political differences with administrative measures and suppressing debate – and they never abandoned them.

The delegates gathered at the congress held in São Paulo showed enormous optimism towards the founding of a legitimate section of the RCI in Brazil. This was also the sentiment of the dozens of greetings received from national sections of the RCI from all continents. With this new beginning, the new Brazilian section embraces the true ideas of the International, and its comrades are willing to fully assimilate its legacy and traditions.

The awakening of youth

The delegates’ enthusiasm is based on the understanding that we are living in a period of historic change, marked by turbulence and upheaval, as highlighted by Jorge Martín of the International Secretariat on the first day of the congress. As examples of this turbulence, he listed the so-called ‘Gen-Z’ revolutions, the important strike movements in Italy and France, the largest concentration of US military power in the Caribbean in 40 years, the farce of the peace agreement in Gaza, and the defeat of Zelensky in Ukraine.

Despite the constant flow of news stories, which gives the impression of chaos, Jorge noted that general trends can be observed beneath the surface of these events. The central factor is the crisis of the capitalist system, a crisis of an organic nature. This is resulting in a readjustment in the relations between the capitalist powers.

This situation is aggravated by public debt, which has grown enormously since the 2008 crisis. The system is paying the price for the capitalists’ strategy of using state debt to get out of the last crisis – now global debt is equivalent to 250 percent of global GDP! This acts as a huge dead weight on the economy, preventing a vigorous economic recovery. This deepens the contradictions of capitalism by reinforcing financial speculation, with capitalists always chasing easy and quick profits.

The political effect of this is that every generation under the age of 30 has only lived under the conditions created by the 2008 crisis. It can therefore be said that Gen-Z is the generation that has only known capitalism in crisis.

Two fundamental characteristics of the new situation have therefore emerged. First, there is a high degree of radicalisation and sympathy for communism in all countries, especially among the younger sections of the population.

Second, there is a growing crisis of legitimacy of bourgeois democratic regimes and their representatives in the eyes of an increasingly broad section of the population. Instead of a march towards Bonapartist or dictatorial regimes, as the former OCI leadership maintained, what we are seeing is an increasing crisis of bourgeois democracy, expressed in the rise of right-wing demagogues such as Donald Trump, and the search for alternatives on the left, such as Zohran Mamdani.

Another effect of the new situation – and one that was a central factor in the debates that preceded the break of the majority of the OCI leadership with the RCI – is a realignment in the relationship between the imperialist powers. At the same time that the US is experiencing a relative decline, China is clearly rising as an imperialist power. In fact, recent agreements involving rare earth elements signify a recognition by the US that it is unable to bend China to its will.

Despite this, the US remains the most powerful and reactionary force on the planet. Trump recognises that the US is experiencing a relative decline – only relative – and seeks to act on that basis. He thus aims to regain control, first and foremost, over the Americas as his priority sphere of influence. This is reflected in the 50 percent tariffs on Brazil, the financial ‘aid’ to Argentina, the impositions on Panama, and the escalation of threats against Venezuela, Colombia, and Mexico.

Absent subjective factor

Jorge Martín also highlighted an important change in the recent political situation. Ten years ago, the crisis was mainly expressed in the dominated and less economically powerful countries. Now it is also manifesting itself in the advanced countries. And the movements that are shaking these countries are not coming from traditional workers’ organisations, but from below, pushing aside the old leaders, unions, and parties.

The inspiring revolts led by Gen-Z are a continuation of the insurrections that took place in the wake of the 2008 crisis. Jorge pointed out that, in all of these movements, the masses demonstrated their total dedication and will to struggle.

But unfortunately, they paid for their initiative with thousands of deaths. In some cases, they achieved partial victories. But even in those cases, soon after, little changed, or things returned to as they were before.

In the global uprisings of 2024–2025, Gen-Z adopted the flag of the anime ‘One Piece’ as a symbol of rebellion: a black cloth with a smiling skull wearing a straw hat, above two crossed tibia bones. This pirate flag is appearing in protests around the world, from Indonesia to Ecuador, from Madagascar to Italy.

This image is associated with the pirate crew led by the protagonist Luffy, who faces the tyranny of a world government and corrupt elites on his journey. The flag has become an immediate emblem for young people who find no inspiration in traditional political parties and ideas. Lacking a genuine reference point from the left, they turn to an imaginary universe to fuel their collective courage.

By raising Luffy’s flag, they affirm their desire for freedom, camaraderie, and a radical transformation of society. This phenomenon expresses enormous potential if this insurgent energy is connected to the genuine ideas of communism, the most powerful inspiration that Gen-Z can embrace, to transform revolt into real social change. These revolts, spread across five continents, reveal Gen-Z’s powerful revolutionary instinct.

The great lesson of all these revolutionary processes, however, is the need for a revolutionary party capable of implementing a programme for the complete transformation of society. It was the lack of this subjective factor that, sooner or later, determined the defeat of these movements.

This subjective factor can develop rapidly, as has been shown several times in history. But it is not enough for an organisation just to grow numerically. It is necessary that it grows on the right basis, so that all the effort is not lost. In this sense, even ruptures and splits may be necessary to advance to a higher stage of development. We are experiencing the beginning of a very favourable situation for building a political alternative for the masses, and the RCI-Brazil is ready to advance this goal.

A correct view of Brazil

In analysing the national situation and the tasks of the RCI in Brazil, Caio Dezorzi emphasised the importance of a correct analysis of the inter-imperialist struggle on a global scale in order to understand what is happening in Brazil. He demonstrated how, by rejecting the former leadership’s mistaken thesis that China is a dominated country and not an imperialist power, it is possible to reinterpret the events in Brazil after the 2008 crisis in a much more accurate way, giving us a far better understanding of these events.

The old leadership, however, could not incorporate these developments into its analysis without questioning its long-held axioms that China is a dominated country and that the development of productive forces has been impossible since 1938. This is based on the fact that Trotsky wrote at the time that the productive forces had stopped growing. This schematic interpretation of Trotsky’s 1938 perspectives led the leaders of the old section to fail to realise their mistakes and to develop a sectarian and dogmatic line.

Caio pointed out, however, that Brazil’s recent political and economic history can only be fully understood in the light of the dispute between the US and China. For example, Bolsonaro faced the same dilemma as Milei in Argentina, which is politically aligned with the US but economically deeply dependent on China. Even in the case of the massacre in Rio de Janeiro, this factor is evident, with Claudio Castro seeking Trump’s support and pressing for the Comando Vermelho to be recognised as a terrorist organisation.

Traces of instability and of the international crisis are also developing in Brazil. Social and economic contradictions are advancing beneath the record rates of employment on the surface. Official data hides a situation of high levels of informal employment, precariousness, and low wages in formal jobs, the deterioration of public services, constant increases in the cost of living, growing deindustrialisation, and the spread of crime and social breakdown. This situation is subject to an unstable international situation, in which Brazil increasingly positions itself as a supplier of raw materials.

Under these conditions, communists need to formulate a set of transitional demands that translate their revolutionary programme into terms that are understandable to the masses, according to their level of consciousness at any given moment. These may include, for example, the nationalisation of American companies; the establishment of Petrobras as a 100 percent state-owned company, from the well to the petrol station; state control of petrol, gas, telecoms, the internet and cable TV; free public services for all, such as health, education, transport, and housing, with all the funding necessary for quality service; and decent employment for all. All of this raises the question of non-payment of the public debt.

The Central Committee that was elected to lead the new section of the RCI in Brazil has a mandate to develop the most appropriate programme for communists to disseminate in the coming period in the country. In each of the 60 countries where the RCI is present, its comrades face the challenge of developing a programme tailored to the conditions in the country in which they are building.

In Brazil, such a programme should take into account, for example, a survey conducted on social media posts, which shows that the younger the person, the more likely they are to make radical and left-wing posts, reaching 48 percent among those aged 18 and under.

At the end of the debates, some amendments presented by the delegates were accepted, and the political document was unanimously approved.

The ideas of Ted Grant

Although there has been a section of the RCI in Brazil since 2008, Ted Grant’s ideas and legacy have never been adequately disseminated in this country. Today, it is clear that this was not accidental. The leadership of the former Brazilian section of the RCI upheld another legacy, that of Pierre Lambert and his political tendency. They had no interest in ensuring that Brazilian comrades had a thorough understanding of the history and ideas of their own International.

A complete change in this orientation was initiated by our cadre school on 22 November, which included a session on the life and ideas of Ted Grant, the founder and main theoretician of the RCI, after the assassination of Leon Trotsky. The lead-off was given by the author of this report, Johannes Halter, and included contributions from comrades on Ted’s life and legacy, which enriched the discussion.

Ted was responsible for keeping the torch of Marxism burning under the most adverse conditions, particularly in the face of the collapse of the Fourth International. One of the important discussions that emerged after World War II was a debate over what was happening in Eastern Europe. The defeat of the Nazis resulted in the Red Army’s occupation of a number of countries that were previously under the control of the capitalist class. The leaders of the Fourth International put forward an analysis that capitalist regimes had been established in these countries under the protection of the Red Army.

Ted Grant, however, saw that, although Stalin’s policy was one of class collaboration via popular fronts, the fragility of the bourgeoisie at that time, and the revolutionary initiative of the masses in these countries, led the bureaucracy to expropriate capital and establish bureaucratic regimes in its own image.

Whereas the leaders of the Fourth International, with their incorrect methods, were disoriented by the developments that followed, such as the Tito-Stalin split, Ted explained that this was a struggle for power between two wings of the same Stalinist bureaucracy. He analysed the development of bureaucratic regimes based on what Trotsky had already characterised as ‘proletarian Bonapartism’, with the Stalinist bureaucracy going further than it would have liked under pressure from the struggling masses.

Post-war economic growth

Another important debate between Ted Grant and the leaders of the Fourth International was over their analysis of the economic situation after World War II. The leaders of the Fourth International maintained that, as Trotsky had predicted before the war, a period of capitalist crisis, revolutionary explosions, and the rise of the Fourth International had now begun. After all, Trotsky wrote that this was the perspective.

Ted was the only one who saw that, according to all available evidence, the capitalist system was entering a period of economic growth. Ted noted that the capitalists were able to restore a certain normality after the war by relying on the collaboration of the social democrats and the Stalinists to contain or divert mass movements.

This situation can only be fully understood if one realises that the end of World War II led to something that Trotsky had not foreseen at its outset. The dynamics of the conflict did not lead to a weakening of the Stalinist bureaucracy, but rather strengthened it to a surprising degree.

Like Stalinism, reformism too was strengthened in this period. The British Labour Party, for example, which, under pressure from the masses, began to implement a genuine programme of reforms. It did so, however, without jeopardising the existence of the capitalist class or the private ownership of the major means of production.

This was the basis for the post-war economic recovery and the postponement of the revolution, at least in Europe. It was therefore the basis for enormous growth in the productive forces, as well as further contradictions, which then led to a new classical crisis of capitalism.

Ted defined this situation as a counter-revolution in democratic form. Failing to understand this, the leadership of the Fourth International continued to argue that crisis and dictatorship were coming. This error of analysis led to political mistakes, such as in France, where the section decided to go underground. This could have been corrected through debate and a revision of this policy by the comrades of the Fourth International.

A faction in the American SWP, led by Felix Morrow and Albert Goldman, developed a position similar to Ted’s on this issue. However, James Cannon crushed them with Zinovievist methods, branding them as ‘London Gangsters’, and replacing debate with manoeuvres and character assassination.

Theoretical errors of the old leadership

Reality, therefore, invalidated Trotsky’s pre-war perspective. This, in itself, should not have been a cause for concern, since a perspective is a working hypothesis that must be revised as events unfold.

The leaders of the Fourth International, however, did not understand this method of analysis and continued to repeat Trotsky’s pre-war perspectives in a dogmatic manner. Lambert maintained, until the end of his life in 2008, that the productive forces had stopped growing, supposedly defending in an ‘orthodox’ manner the ‘legacy of Trotsky’ and the ‘Transitional Programme’.

Lambert’s position was inherited and defended by the majority of the CC of the OCI within the RCI, and led to its error in analysing China today, for example. Alan Woods, in his preface to the Brazilian edition of The History of Philosophy: A Marxist Perspective, demonstrates how the basis of this mistaken position is not dialectical materialism, but formal logic.

“Once it is distorted into a rigid and ossified schema, Marxism is turned into its opposite – from a profound and scientific method into a lifeless dogma that can be mechanically applied to any situation or context that is required.

To cite one example which may be familiar to you: capitalism is unable to develop the productive forces under any circumstances.

Therefore, China cannot have developed the productive forces.

Therefore, China is a backward, undeveloped, dominated semi-colony controlled entirely by the USA.

Therefore, the alleged conflict between China and US imperialism is merely an invention or a figment of the imagination.

The logic of this seems impeccable, and, in fact, it faithfully follows the rules of formal logic. Once one accepts the initial proposition, the rest follows, as night follows day. […]

The theory that, in the age of imperialism, no development of the productive forces is possible, is regarded as an absolute proposition valid for all time – a magical key that opens all doors.

It is based on a misinterpretation of what Trotsky wrote in 1938 Trotsky wrote in The Transitional Programme, where he pointed out that the productive forces had ceased to grow.

That was correct at that time. But Trotsky never claimed that this was a proposition that had a universal application, independent of time and space.

In fact, he warned against this in advance:

‘But a prediction in politics does not have the character of a perfect blueprint; it is a working hypothesis… One must not, however, get intoxicated with finished schemata, but continually refer to the course of the historic process and adjust to its indications.’ (Trotsky, Writings, 1930, p.50)

By turning what was a conditional prognosis into an absolute assertion, valid for all time and applicable in all circumstances, the sectarians have turned Trotsky’s scientific analysis into a complete nonsense.”

That is why we criticised the method of analysis used by the majority of the CC of the OCI. We presented a political and theoretical criticism that aimed to draw attention to this problem and correct it. However, as we have seen, this was not a problem exclusive to the majority of the CC of the OCI. They inherited this error from Lambert.

Readers can see for themselves the similarity between the political report defended by the majority of the OCI CC, available here [in Portuguese], and the translation by RCI comrade Taisa Leonardo of a 20-page document by Pierre Lambert, dated January 1969, entitled ‘The Actuality of the Transitional Programme’, available here [in Portuguese]. The original French can be read here.

Both the OCI’s document and Pierre Lambert’s share the same assumptions as a starting point for analysing the situation in the year 2025 and at the end of the 1960s respectively. These assumptions include:

- The productive forces have stopped growing.

- The productive forces have become destructive forces.

- The only barrier preventing victory is the crisis of revolutionary leadership.

- If the productive forces grow, then the possibility of a proletarian revolution would be refuted by history and we should adapt to the capitalist system.

But it was not Lambert who first developed these positions. Lambert was not a theorist and inherited his ideas first from Pierre Frank, the leader of the French section at the time of Lambert’s youth, and then from Ernest Mandel and Michel Pablo. This error therefore stems from the post-World War II leaders of the Fourth International’s misunderstanding that Trotsky’s perspectives were not historical laws. They were based on the objective conditions of the historical period Trotsky was analysing until his assassination.

Historical patience

A third example of the difference between Ted Grant’s method of analysis and that of the other leaders of the Fourth International concerns the understanding of the isolation of the Fourth International and the working-class movement. Shortly before Trotsky was struck with an ice pick by a Stalinist agent, he had made a prediction that in ten years the Fourth International would become the dominant force in the labour movement.

A decade later, not only was the Fourth International not hegemonic, but it was struggling to survive. It was a series of small national groups that were isolated from the working class. Faced with this fact, the leaders of the Fourth International drew different conclusions, all equally false.

One was ‘Pabloism’, with its theory of camps and the tactic of dissolving into the Stalinist parties. Another was ‘Mandelism,’ which revised the perspective of the Fourth International’s leadership after World War II, making a 180-degree turn to say that capitalism was in a new historical stage and the proletariat had become bourgeoisified, even in 1968.

Ted Grant maintained that, however surprisingly long the isolation of the Trotskyists was proving to be, it could be understood objectively. Sooner or later it could be overcome, but not by some trick or magical shortcut applied by a clever leadership.

It would be the very development of the contradictions inherent in capitalism that would lead to new crises, the beginning of a new economic situation, and social turmoil. It would be the masses’ own experiences of the ‘communist’ and reformist parties, with all their betrayals and mistakes, that would open up new political opportunities and turn the tide in the Trotskyists’ favour.

The Trotskyists’ tactics, Ted emphasised, should first and foremost take into account the masses’ connection to the organisations they had historically built. He explained that, at first, the masses always tend to look towards what is familiar to them, and what they consider to be the simplest way to solve their problems. Unlike Marxists, the masses do not learn from books, but from their own experience.

Until new political conditions arose, Ted maintained that Trotskyists should patiently work within the traditional working-class organisations in which the masses were organised and which they used. They should do so without dissolving their own organisation, as Michel Pablo proposed, without adapting to the petty bourgeoisie or to opportunist leaders, and without hiding their banner and programme.

This was the tactic by which Trotskyists could best prepare their forces for the new revolutionary opportunities that were still on the horizon.

Zinovievism and ‘Trotskyism’

These are just a handful of examples of the controversies between Ted Grant and the other leaders of the Fourth International. It became increasingly clear that behind the various differences was a question of method. Ted advocated for dialectical materialism as the method for investigating each new problem and developing a policy. Meanwhile, the self-styled leaders of the Fourth International applied all sorts of eclectic methods.

Added to these constant political and theoretical clashes, an increasingly Zinovievist regime was developing in the Fourth International and in the various sects that emerged from its collapse.

This bureaucratisation of the regimes of these organisations is unsurprising. Unable to apply the Marxist method of analysis to interpret reality, the so-called Trotskyist leaders were incapable of formulating a correct political line. Without that, the political regime of their organisations could not be guided by democracy and freedom of discussion. Instead, to save the supposed authority of their leaders, it was necessary to suppress dissent and defeat critics even before ideas were debated.

Brazilian comrades of the RCI experienced this type of bureaucratic Zinovievist regime firsthand. The secret faction of Serge Goulart sought in various ways to suppress discussion and dissent, resorting to sanctions, slander, and administrative manoeuvres.

In Brazil, the majority of the CC justified its decision to split by claiming that the RCI’s leadership had committed a ‘crime’ in demanding that, until the scheduled national congress was held, the wave of sanctions against the leaders of the ‘Fraction in Defence of the International’ be suspended.

The RCI also asked that manoeuvres like merging regional committees and changing the responsibilities of full timers – all to bureaucratically undermine the minority – be reversed. The leadership of the International asked that the focus be on political discussion and that differences be resolved democratically at the congress.

Ted’s work with the so-called leaders of the Fourth International ended in 1965. After three bureaucratic expulsions by the Fourth International’s leadership, Ted came to the conclusion that the defence of Trotsky’s legacy could only be done far away from the so-called ‘Trotskyists’ and their tendency towards setting up ‘fronts of revolutionaries’. From then on, he devoted himself to establishing an independent tendency based on the true ideas and organisational methods of Trotsky and Marxism.

In conditions of extreme isolation, against the pressure of imperialism and Stalinism, which both came out of WWII strengthened, Ted was responsible for keeping the torch of the ideas of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky burning. The contrast between his clarity and the decline of the Fourth International was not limited to tactical differences or personality issues. It represented a profound clash of methods.

While the leaders of the Fourth International sank into Zinovievism, dogmatic formalism and eclecticism, Ted Grant rigorously upheld and applied dialectical materialism. He understood that perspectives are working hypotheses to be revised in accordance with the real situation, and that there are no shortcuts or magic tricks in building the revolutionary party.

A profound lesson left by Ted Grant’s life is that political clarity is inseparable from attention to Marxist ideas and theory. Theoretical weakness and an inability to convince through free debate have always led so-called Trotskyists to bureaucratisation and the use of Zinovievist tricks to suppress dissent. This type of deviation always leads to splits and crises.

Ted founded a tradition – of which the RCI and its members are heirs – on the solid foundations of Marxist ideas, enriched by the experience of decades of struggle. His legacy is not just a set of documents, but a lifetime’s proof of the importance of Marxist theory, patience, and revolutionary audacity.

A profound lesson imparted by Ted, and learned by the participants of our cadre school, was that it was through the development of capitalism’s contradictions that a new period of revolutionary opportunities opened up, which allowed the Marxists to overcome their isolation. What we have been experiencing since the 2008 financial crisis is, therefore, a spectacular confirmation of the economic and political perspectives developed by Ted Grant.

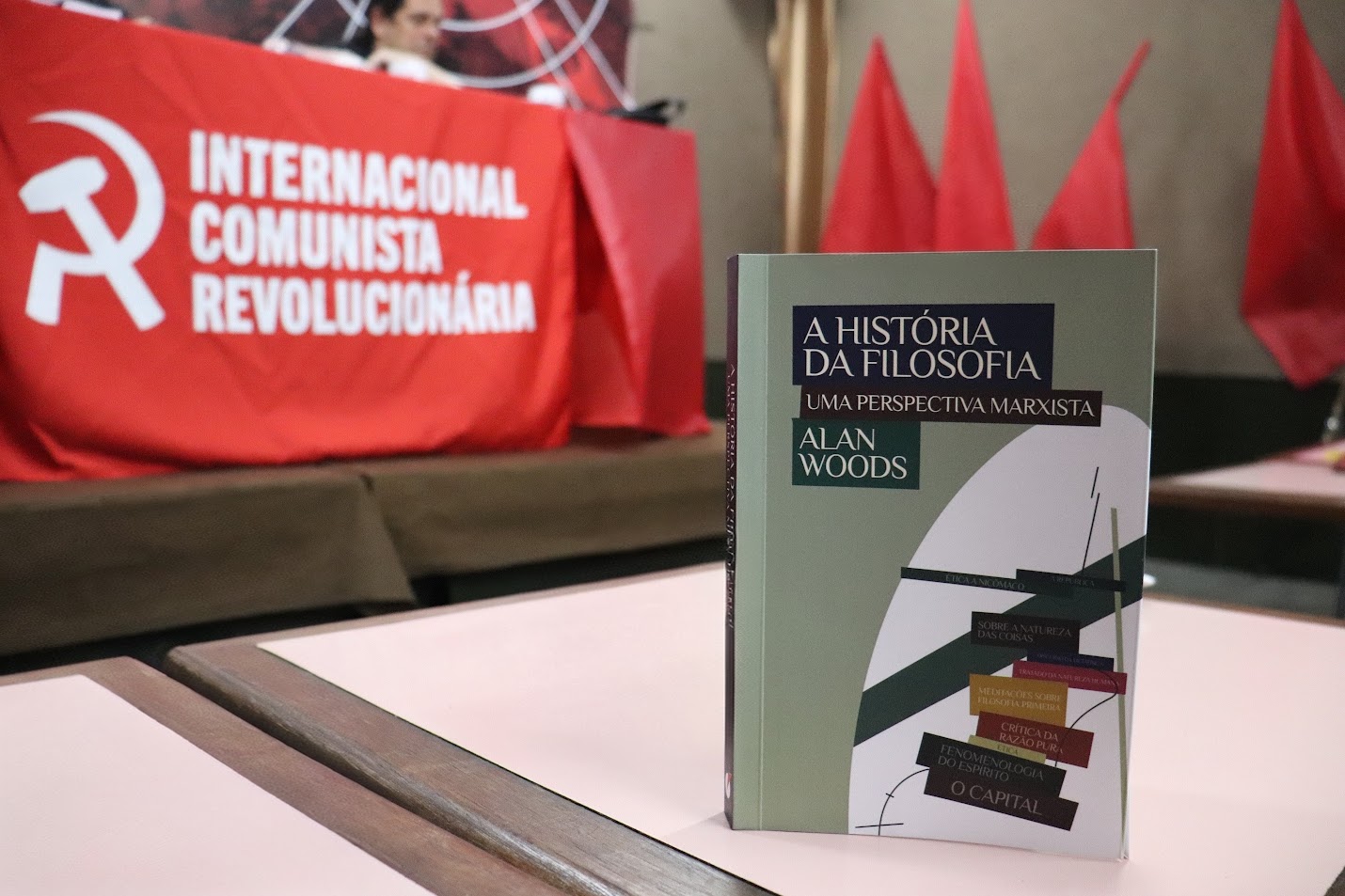

Launch of The History of Philosophy: A Marxist Perspective

The founding congress of the new RCI section in Brazil also featured a session dedicated to the launch of the Portuguese edition of Alan Woods’ book The History of Philosophy: A Marxist Perspective [available here in the original English from Wellred Books]. On Saturday afternoon, delegates and guests gathered in the auditorium for a presentation of the book by Jorge Martín.

The launch of Alan’s book breaks a seven-year drought, as, for all that time, the former leadership refrained from publishing a single book in Brazil. Meanwhile, the Mexican section published eight books in 2024 alone. Not to mention that, since 2021, the International has launched a worldwide campaign in defence of Marxist theory and against postmodern ideas, which had very little resonance in the Brazilian section at the time.

The book The History of Philosophy: A Marxist Perspective, in particular, was systematically refused publication in Brazil by the former leadership. Excuses were constantly made, and four years passed with the book gathering dust in a drawer. Brazilian comrades who wanted to read it had to purchase the work in English or Spanish at international events.

Two and a half months after the split, however, communists of the Brazilian RCI managed to organise the translation of the book, which shows that the decision not to publish it was political.

The choice to publish this specific book was also no accident. The Brazilian comrades are convinced that the best way to build the new section of the RCI in Brazil is to found it on the solid rock of Marxism, and to understand and defend Marxist ideas as the greatest theoretical achievement of human thought.

After the book launch, the audience was invited to attend another session of our cadre school, which featured a rich discussion on dialectical materialism, introduced by Marcos Andrade. A surprising number of delegates and guests took part in the discussion, highlighting the comrades’ thirst to debate philosophy and to learn and assimilate a Marxist understanding of the subject.

In the coming months, comrades of the RCI Brazil will devote themselves to studying each chapter of The History of Philosophy: A Marxist Perspective. They will also invite all friends of the RCI to join the ‘voyage of discovery’ announced by Alan Woods in his introduction and so well reinforced by Jorge Martín’s presentation during Saturday’s launch.

RCI as inspiration: are you a Communist?

Comrades from various sections of the RCI participated in the congress. Brazilian comrades left inspired by the fantastic progress of the International in countries such as the United States, Mexico, Canada, Italy, and Great Britain. The International is now present in 60 countries and, in all of them, incredible gains are being made on the basis of the radicalisation of the youth.

The common denominator for progress in all of these places has been the worldwide ‘Are you a Communist?’ recruitment campaign, launched in August 2023. This campaign combined a systematic orientation towards the youth, especially in schools and universities, with a dedicated focus on theoretical training and the development of material for the theoretical and political education of young people.

Reports on the progress of the RCI around the world deeply inspired the Brazilian comrades who participated in the congress. This was evident during the collection held on Friday night, led by Rennan Valeriano.

All branches in Brazil were called upon to announce the total amount they would contribute to the collection. At the end of these announcements, it was revealed that the comrades had exceeded the initial fundraising goal. Incredibly, we raised more than R$30,000 – this at the congress of an organisation that has just been born! Another demonstration of the comrades’ enormous enthusiasm was the auction of a cap from the Canadian section of the RCI, which was the subject of intense bidding between several comrades. It was finally sold for R$500.

One of the most exciting moments of the congress came at the end of Sunday’s session. The leader of the Italian section, Alessandro Giardiello, took to the floor to declare that, from everything he had seen during the event, the Brazilian comrades had won his confidence that they were capable of building a genuine section of the RCI in Brazil.

Our confidence and security in our future derive from the fact that we are advancing armed with Ted Grant’s legacy and, most importantly, his method of analysis. This theoretical arsenal represents the living ideas of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky, that is, the authentic thread of revolutionary continuity that goes back to the Communist League and which has been preserved for us.

On this basis, we will build a genuine section of the Revolutionary Communist International in Brazil. If Ted Grant’s ‘historic patience’ was vital to preserving the thread of continuity of Marxism under the most adverse conditions, it now finds its dialectical complement in the ‘revolutionary impatience’ of Gen-Z.

The theory preserved with such effort by Ted and the comrades of the RCI will serve as a weapon in the hands of the youth, which has nothing to lose. These ideas, the ideas of genuine Marxism, constitute the cornerstone on which we will build the revolutionary party that history demands in Brazil, and the International that humanity needs throughout the world.