The Russian Revolution led to a corresponding revolution in every type of art—especially film. Under the early Soviet Union, Russian film advanced rapidly into a leading light of world cinema and transformed the medium forever.

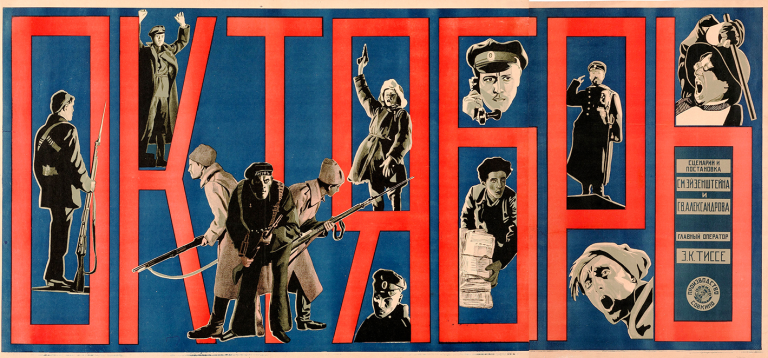

Of all the films to be created in this period, one of the greatest is October, directed by Sergei Eisenstein. Not only is it a masterful depiction of the revolution, but it exemplifies the incredible innovation of early Soviet cinema.

The Russian Revolution and art

After the revolution, the Bolshevik Party took sweeping steps to provide culture to the worker and peasant masses. They lifted the extreme censorship that existed under the autocracy, major art collections were made public, and the government created a number of new institutions to promote the arts.

Artists were given a level of freedom and patronage that was unthinkable under the old regime. As a result, practically every form of art flourished in the early Soviet Union. There were great painters, like El Lissitzky and Malevich, great writers like Mayakovsky, and, of course, great filmmakers.

Eisenstein himself was a product of this. He started to work for state-sponsored theater companies in 1920 and rapidly rose through the ranks. He was then commissioned by the State Committee for Cinematography in 1924 to create his first feature film, Strike.

Kuleshov and the montage

At the time of the revolution, film was still a fairly new medium that was in the process of developing its own conventions. The Soviet filmmakers were eager to develop an artistic language for film that was distinct from theatre and literature.

In the initial days of the Soviet state, during the civil war, blank film was in very short supply. This led filmmakers to experiment with film stock and try to make movies out of preexisting footage.

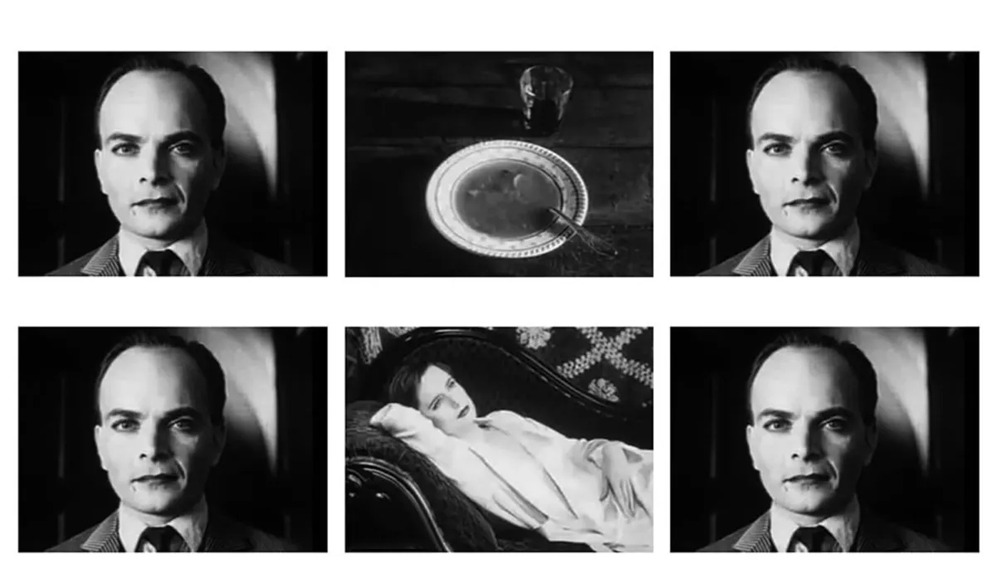

Here arose the Soviet Union’s most famous contribution to film: the theory of montage. Filmmakers working under Lev Kuleshov discovered that the meaning of a shot is significantly impacted by the images that surround it.

In his most famous experiment, Kuleshov takes a still shot of a man with a blank expression and splices it with a series of different images—a bowl of soup, a woman lounging, and an open casket. In this way, he derives a series of different emotions–-hunger, lust, and sorrow—from a single facial expression.

The “Kuleshov effect” immediately became a staple in Soviet filmmaking, and can be observed

in virtually every film that has been made since.

Dialectics in Eisenstein

Eisenstein took this concept and developed it further by infusing it with an understanding of dialectical materialism, the philosophical outlook of Marxism.

The basic tenet of dialectics is that everything exists in a state of constant motion, and that motion itself is created through contradiction. In all realms of existence, we see the interpenetration of seemingly opposite forces. Atoms are bound together by opposing negative and positive forces. Living bodies are constantly shedding off dead cells. And history is propelled forward by the struggle of competing economic classes

Eisenstein pointed out that all art contains contradictions, and it’s this conflict that creates pleasure and meaning. For example, musical rhythm is created by the contradiction between the notes and the silent intervals.

Montage is another example of dialectics in art. Eisenstein explained that meaning in film is created “from the collision of independent shots—shots even opposite to one another…”.

Through conscious manipulation of this process, he found that it was possible to communicate more abstract ideas than can be depicted literally. He saw montage as a way to free film from its technical limitations and elevate it to a higher level. He even thought he could make a film that explained Marx’s Das Kapital using this method—although he never got the chance to put this idea into practice.

Revolution and the masses

Eisenstein’s montage takes on its highest form in October. With 3,200 unique shots, the film is rich with symbolism and metaphors. It’s remarkable how much it manages to say through visuals alone.

The revolution isn’t depicted as a struggle of individuals, like it is by bourgeois historians. Instead of following individual characters, October follows the struggle of different classes. This is depicted through clashing symbolism.

Rifles, sickles, and machinery are used as visual shorthand for the revolutionary masses: the soldiers, peasants, and working class. On the other hand, the ruling class is depicted almost in a caricature. We see bourgeois men wearing top hats and monocles, and the women carrying around fancy parasols.

Religious imagery is constantly posed against autocratic imagery. This communicates the reactionary role of the Russian church, which supported the monarchy against the revolution to the very end.

Typical of Eisenstein’s early films, there is no main character. His rapid-fire editing allows us to focus on the actions of many different individuals at once and see how they intersect.

Lenin is depicted as the revolution’s leader, but he’s only on screen for a few minutes. This is true to his actual role, as not the revolution’s instigator, but as its guide. We spend the bulk of our time on the countless unnamed heroes of the revolution that carried through the work on the ground. If there is a protagonist at all, it is the Russian proletariat, led by the Bolsheviks.

There is one historical inaccuracy in October: the way that Eisenstein depicts the storming of the Winter Palace as a pivotal, full-blown battle. In reality, the affair was considerably more low-key. However, the scene communicates a deeper truth. It shows the masses of workers and soldiers, breaking through the palace gates like a flood. They stream through the halls of power, tearing up the trappings of the old regime. The scene is a microcosm of what actually happened in Russia on a grander and more general scale.

Kerensky and Kornilov

One of the best scenes in the films depicts the conflict between Kerensky and Kornilov, the chief counterrevolutionaries of 1917. This sequence captures all of the best qualities of Eisenstein’s work.

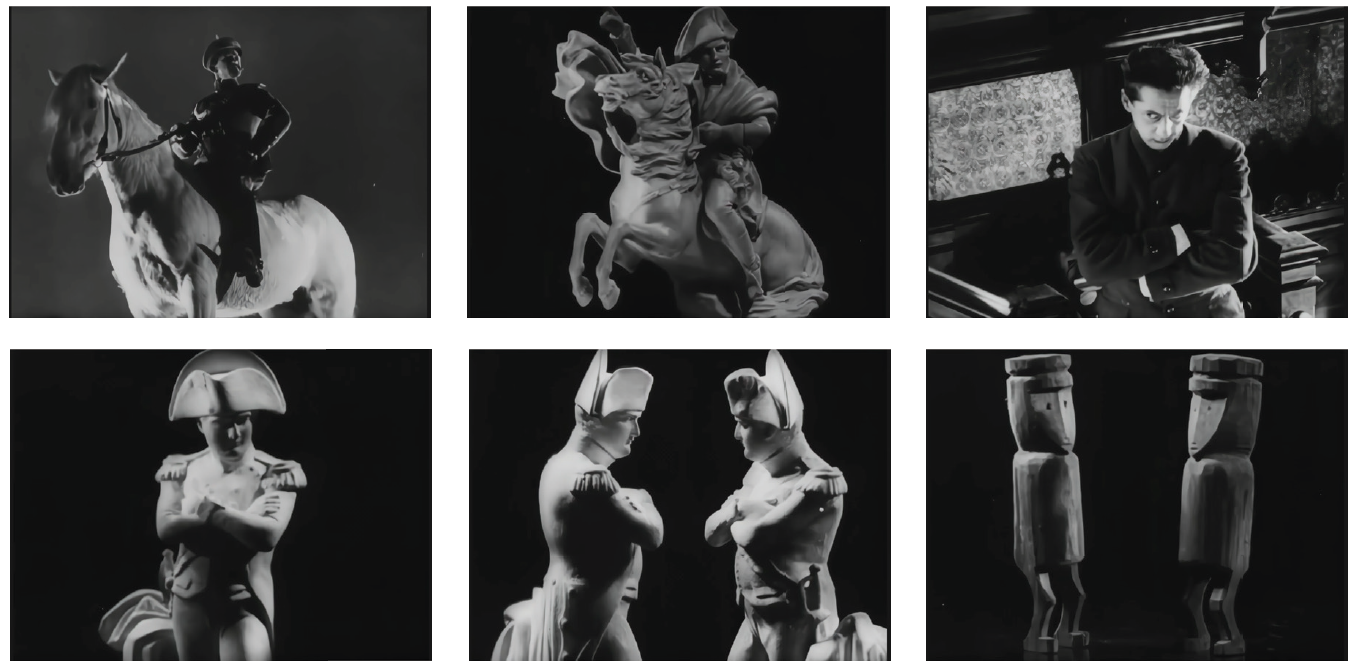

When we first see Kerensky, we find him climbing the stairs of the Winter Palace, depicting his reactionary rise to power. We cut between him, a statue of Napoleon, and shots of a mechanical peacock. This reveals Kerensky’s real character, as a pompous, pretentious, aspiring dictator.

As Kerensky marvels over riches left behind by the Tzar, we cut to Kornilov preparing his coup, and then again, back to Napoleon. One man claims to be fighting for democracy, and the other, for God and monarchy. But Eisenstein reveals them to be essentially the same, both in terms of their class interests and their personal characters.

Then, we cut to an elaborate statue of Jesus, further strengthening the association between the Church and political reaction. This image of Jesus then slowly fades into a whole series of different religious icons. First we see Hindu, Aztec, and Shinto gods, and eventually, shots of prehistoric wooden idols. Eisenstein leads us to the conclusion that all religion is essentially the same: a product of time when humans held extremely limited knowledge, and needed to invent gods to explain the world.

Later on, shots of Kerensky and Kornilov jump to a shot of two Napoleons staring each other down. Then, we cut from this to two of the wooden dolls from earlier.

Here, Eisenstein communicates a very profound idea. Religion, dictatorship, and, ultimately, class rule itself are all products of a more primitive time in human history. When the workers take power, they’ll sweep away this backwardness. The forces that Kerensky and Kornilov fight for are doomed to be left behind by history.

We then see workers fraternizing with Kornilov’s troops. They’re won over by the Bolsheviks’ slogans and they dance in celebration of the revolution. The forces of counterrevolution melt away. Kornilov is arrested and we find Kerensky passed out on his bed, demoralized and powerless.

We cut to the two Napoleon statues from before—except now, they are destroyed. From this point on, real power is in the hands of the workers, and we watch as they begin to prepare an insurrection.

This sequence is just one example of what makes October a masterpiece. In scenes like this, Eisenstein beautifully captures the full emotional and historic weight of the revolution through the unique artistic language of film editing.

As Anatoly Lunacharsky put it, “With the help of an original construction method Eisenstein has managed not simply, as it were, to chronicle October in prose but to transform it into a real poem…”

Capitalism and the soul of cinema

Almost 100 years after its release, October still feels fresh and exciting. Eisenstein manages to say more through the medium of silent film than most modern big budget films do with sound and multimillion dollar special effects.

As a matter of fact, it feels more and more rare that films released today try to say anything of importance at all. Great films still come out occasionally, but they come buried beneath thick mounds of corporate crap.

This can largely be blamed on the capitalist market. When films are produced as commodities, there’s incentive to appeal to the lowest common denominator. Innovation is stifled in this environment.

But it’s deeper than just a financial question. It’s also the spirit of the times that hampers artistic development. Even films that are technically innovative tend to have shallow ideas behind them. Capitalism today inspires nothing but depression and cynicism. Who has the drive to produce something new and exciting when most people today don’t even believe that they have a future?

The October Revolution liberated art and gave everyone the opportunity to express themselves. But it also inspired people to use this freedom to the fullest. Each individual felt themselves to be directly participating in the creation of a new world. The artists of the time felt it was their duty to depict these changes, and to furnish this new society with beauty and creativity.

We need to replicate October and abolish capitalism once again. Under communism, art will be liberated from profit and we’ll unleash an unprecedented wave of human creativity.