There are more people than ever who want to overthrow capitalism through revolution. But how can the working class achieve this? How can we organize a socialist revolution?

The year 2020 has turned the world upside down. COVID-19 has exposed the complete bankruptcy of the capitalist system in the eyes of millions of people. The mantra that we are “all in this together” has been exposed for the lie that it is. All over the world, profits have come before needs. While millions of people have lost their jobs, the rich are richer than ever. In the United States, the richest country in human history, millions of people go hungry.

The economic crisis triggered by COVID-19 adds to what has been a lost decade. Since the previous crisis in 2008, austerity has ravaged public services, workers have seen their real wages stagnate or fall, while youth are the first generation to be poorer than their parents since World War II.

It is on this basis that socialist ideas are making a comeback. This year, the Victims of Communism Foundation, which cannot be accused of a favourable bias toward Marxism, released its annual survey and found that 49 per cent of 16- to 23-year-olds (Gen Z) have a favorable view of socialism, up nine points from 2019. Among Americans as a whole, that number has risen from 36 per cent to 40 per cent. In the land of MacCarthyism, 18 per cent of Gen Z think communism is a fairer system than capitalism!

These numbers are not as surprising as one might think. The younger generation in particular has experienced nothing but austerity, declining living standards, terrorism, imperialist interventions and environmental destruction. The golden age of capitalism, the 60s and 70s, is dead and buried. More people than ever before want to overthrow the capitalist system through revolution.

The conditions are ripe

The reality is that the capitalist system has long been a brake on human development. It could have been overthrown long ago by a revolution led by the working class. Why hasn’t this happened yet?

It is certainly not because the objective conditions to build a socialist society based on super-abundance are lacking. There is no doubt that from the economic point of view, all the conditions are there to satisfy human needs. We have the means to feed the entire human population. The technology and knowledge exist to produce the necessities of life in harmony with nature. Large companies like Amazon and Walmart show that it is possible to organize production and distribution on a global scale. Many difficult or dangerous jobs could be replaced by machines.

Marx explained that the capitalist system “creates its own gravediggers” by creating the working class – the class that builds the buildings around us, produces the consumer items we need, and distributes goods and services. He also explained that socialism was not just a good idea that appeared in the heads of a few thinkers. He showed that under capitalism, it is the working class that can lead the struggle to establish a socialist society by taking control of the means of production. Marx explained that this class had to organize to overcome the resistance of the bosses, bankers, CEOs and their politicians. This class today (unlike in Marx’s time) forms the overwhelming majority of society. Once mobilized and determined to overthrow capitalism, nothing can stop it.

So why hasn’t the working class overthrown the capitalist system with a revolution yet?

Blame the workers?

Leon Trotsky, the leader of the Russian revolution alongside Lenin, wrote a fantastic essay shortly before his death entitled “The Class, the Party and the Leadership—Why was the Spanish Proletariat Defeated?”

As the title indicates, the text looks at the Spanish revolution of 1931-39, and the reasons for its defeat. We will go into some of the details of this revolution later. Suffice it to say for now that despite numerous uprisings, spontaneous initiatives by workers to take control of factories, and by peasants to take control of their land, despite strong trade union organizations and a rich tradition of struggle, the Spanish working class did not take power. A fascist regime led by Francisco Franco was established in 1939, and lasted until the 1970s.

Trotsky’s text, though short (Trotsky was assassinated before he could finish it), is a gold mine of lessons on how to explain revolutionary defeats – and how to prepare for victories. This text should be required reading for every socialist today.

“The Class, the Party and the Leadership” opens with a polemic against a small, allegedly Marxist journal, Que faire? In one article, Que faire? explains the defeat of the Spanish revolution by the “immaturity” of the working class. If the Spanish revolution failed, then the fault lies with the masses themselves.

This idea of blaming the masses is one that is very common in the labour movement today. Indeed, for many on the left, the fault lies with the working class itself for not having already overthrown capitalism.

The working class is allegedly “too weak” to change the world. This was one of the explanations of some leftists for the failure to complete the Venezuelan revolution, which has been going on since the early 2000s. Despite a historic mobilization during the 2002 coup, despite voting for Hugo Chavez’s Socialist Party (PSUV) repeatedly, despite workers taking control of their workplaces, and despite resisting further coups since 2019, there are still people who say the working class is too weak.

For example, in “The Political Economy of the Transition to Socialism” Jesús Farías, a leading member of the PSUV, stated, “We can say without fear of being mistaken, that one of the main obstacles for a more accelerated development of the social transformations in the country lies in the organisational, political and ideological weakness of the working class, unable to play today its role as the main motor force of social progress.”

Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek finance minister in the 2015 Syriza government, is another example of this trend. In a 2013 article, amusingly titled “Confessions of an Erratic Marxist,” he explained that the crisis in Europe is “pregnant not with a progressive alternative but with radically regressive forces.” He was saying this just as the Greek working class had staged 30 general strikes since 2008! Having no confidence in the working class and seeing only the possibility of “regression,” he claimed that the only option was to create a broad coalition “including right-wingers” in order to save the European Union, and “save capitalism from itself.”

Other journalists, intellectuals and supposedly left-wing personalities say that the working class does not want change, and is not attracted by a “left” program. This is the case of Paul Mason, a well-known British left-wing journalist.

In Britain, we have hundreds of thousands of people who have enthusiastically joined the Labour Party since Jeremy Corbyn, a self-proclaimed socialist, became party leader in 2015. Since his 2019 election defeat, Corbyn is no longer leader; the party’s right wing has regained control under Sir Keir Starmer, who has begun his dirty work of purging the party’s left.

Mason, following Corbyn’s defeat, argues that for the “traditional working class” in Britain, certain “parts of the left’s agenda turn them off: open immigration policies, the defense of human rights, universal welfare policies, and above all anti-militarism and anti-imperialism.” Universal welfare policies, how horrible! He adds, “Does it help tell a story of hope to an electorate that has become terrified of change?”

So the problem here is that working people supposedly don’t want change—are terrified of change. The logical conclusion for Mason is to support Keir Starmer, the moderate leader of the British Labour Party. Mason has completely lost faith in the ability of the working class to change society—assuming he ever had that faith.

What all these ideas have in common is that it is the workers themselves who are unwilling or unable to change society.

These ideas betray the fact that these people have no confidence in the working class to make a revolution, to change society and run it themselves. These ideas are promoted by various journalists, liberals and academics. However, they also infiltrate the labour movement through the union bureaucracy. More often than not, union leaders blame the workers they were elected to lead because the workers supposedly “don’t want to fight”.

A crisis of leadership

What do Marxists respond to these arguments? Why hasn’t the working class overthrown capitalism yet?

The starting point for Marxists is the fundamental role of the working class in changing society. Marxists have nothing in common with the pessimism and cynicism of those intellectuals and journalists who have contempt for the working class. It is not true that the working class is “too weak” to overthrow capitalism. The reality is that countless times in the history of the last 100 years, workers have risen up to overthrow their exploiters and change society. They’ve done everything they could to do so, on multiple occasions.

But almost every time, it is the leaders of the workers’ movement, either of the unions or the workers’ parties, who put a stop to the movement. They make compromises with the capitalist class, rather than trying to take power. Dozens of revolutions have been held back in this way by the leadership of the movement. In his Transitional Program, Leon Trotsky correctly explains that “the historical crisis of humanity is reduced to the crisis of revolutionary leadership.”

However, we must be careful not to fall into a caricature of this position. Marxists do not defend the idea that workers are always ready for a revolution, that they are simply waiting for socialist leaders to show the way. To say that the leadership of the workers’ movement acts as a brake does not mean that if we had socialists at the head of the unions, that if only we had a revolutionary organization at the head of the workers’ movement, then a revolution would break out immediately and automatically succeed in overthrowing capitalism.

It is not true that the workers are always ready to fight and are just waiting for good leaders. A mass movement does not come about with the snap of a finger. However, history shows that there are critical moments in history when the masses enter into struggle: revolutions. The important questions for any activist who wants to change the world are: how can we organize our class, the working class, to overthrow capitalism? What is the role of socialists to achieve this? How can we prepare for it?

Class consciousness

The class consciousness of workers does not evolve in a straight line.

It is through a long historical process that workers have come to understand the necessity of organizing themselves. Trade unions were created to defend the workers in the ongoing struggle against the bosses. Eventually, workers created organizations, parties, to express their political aspirations. Marx explained that without organization, the working class is only raw material for exploitation. Through its history of struggle, the working class comes to participate in politics, through unions or other organizations. This process is uneven and different from country to country.

Coming to the conclusion that it is necessary to organize is one thing; coming to the conclusion that it is necessary to have a revolution to overthrow capitalism is another thing entirely. The working class, when it enters into struggle, does not automatically come to revolutionary conclusions.

In fact, consciousness is not revolutionary. Consciousness is generally very conservative. People cling to old ideas, to traditions, to the comfort of what is known, and they just want to be able to live in peace under decent conditions. Who can blame the workers for thinking this way? No one wants major upheaval in their lives. Workers don’t take jobs to go on strike.

Revolutions are inevitable exceptions in history. Workers are not constantly in struggle; on the contrary.

However, there are times when the status quo is simply no longer sustainable. Millions of people are fed up. Austerity falls on workers. The cost of living rises while wages stagnate. Public services are privatized. The rich are getting richer, in plain sight.

It is not revolutionaries or socialists who create revolutions. It is capitalism that creates the conditions that force millions to revolt. Millions of workers, apathetic one day, are in the streets the next day. Yesterday’s consciousness, which was lagging behind the events, catches up with reality with a bang. And that’s when revolutions happen.

Very often, it is an “accident” that starts a revolution. The Arab revolutions of 2010-2011 started in Tunisia when a young street vendor who immolated himself outside the local governor’s office. This was the spark that lit the fire. A mass movement followed, culminating in the overthrow of the dictatorship in Tunisia. The movement then spread to Egypt and then to the entire Arab world. The anger that had been building up for decades just needed a spark. In almost every revolution, you can find a similar event.

English Wikipedia., CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia

Commons

What is a revolution? Trotsky, in his History of the Russian Revolution, explains it thus :

The most indubitable feature of a revolution is the direct interference of the masses in historical events. In ordinary times the state, be it monarchical or democratic, elevates itself above the nation, and history is made by specialists in that line of business – kings, ministers, bureaucrats, parliamentarians, journalists. But at those crucial moments when the old order becomes no longer endurable to the masses, they break over the barriers excluding them from the political arena, sweep aside their traditional representatives, and create by their own interference the initial groundwork for a new régime. Whether this is good or bad we leave to the judgement of moralists. We ourselves will take the facts as they are given by the objective course of development. The history of a revolution is for us first of all a history of the forcible entrance of the masses into the realm of rulership over their own destiny.

This quote perfectly sums up the essence of a revolution. It is above all the masses, today composed overwhelmingly of workers, who enter the stage of history.

If we look at the last 100 years and more, there has been no lack of revolutions. In fact, not a decade has passed without at least one major revolution.

The Russian revolution of 1905 and 1917; the German revolution of 1923 and the Chinese revolution of 1925-27; the Spanish revolution of 1931-37, the mass strikes in France in 1936; the revolutionary wave in Italy, Greece, France between 1943 and 1945 and the Chinese revolution of 1949; the revolution in Hungary in 1956; May ‘68 in France; the Chilean revolution of 1970-73, the revolution in Portugal in 1974; the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua of 1980-83, the revolution in Burkina Faso of 1983-87; the revolutionary overthrow of the dictatorship in Indonesia in 1998; the revolution in Venezuela under Hugo Chavez in the 2000s; the Arab revolutions of 2011.

The list could go on. History is punctuated by moments when the masses can’t take it anymore, take to the streets, and take their destiny into their own hands.

Revolutions can be compared to earthquakes. No one can predict exactly when an earthquake will occur. And earthquakes don’t happen often. But we can study tectonic plates, know where the conditions for an earthquake to occur are. Earthquakes don’t happen all the time, but they are ultimately inevitable.

It is the same with revolutions. No one can predict exactly when a revolution will come. But we can study economic conditions, see the rising anger among workers, and predict a revolutionary epoch.

The difference is that a revolution is made by human beings. We can prepare for it, and we can play a role in making sure it ends in victory. How can we do this?

Spontaneity?

How are revolutions carried out in practice? If workers could simply overthrow capitalism in one fell swoop, there would be no need to theorize about revolution. There would be no need to debate ideas, programs, concrete measures, in the workers’ movement. There would be no need to create organizations that defend one program or another.

Among the anarchists, there is a lot of talk about the spontaneity of mass movements. The various anarchist theories almost all come back to the idea that the masses can somehow spontaneously achieve a classless society. Kropotkin, for example, in his most famous article on anarchism, explains that his contribution was “to indicate how, during a revolutionary period, a large city – if its inhabitants have accepted the idea – could organize itself on the lines of free communism.” He thus implies that the workers could spontaneously overthrow capitalism with a revolution. Kropotkin does not, however, explain how the inhabitants “accept the idea” of communism.

There is no doubt that there is an element of spontaneity in all mass movements, in all revolutions. It is even a strength at the beginning. Spontaneously, millions of people who were not involved in politics pour into the streets, and take the ruling class by surprise. More often than not, the outbreak of a revolution surprises even hardened revolutionaries. At the time of the February Revolution in Russia in 1917, the Bolsheviks in Petrograd were so far behind events that they advised, on the first day of the demonstrations, not to go out into the streets!

But is spontaneity enough to overthrow capitalism? History shows us that it is not.

And in fact, the reality is that in every movement, every struggle, every revolution, no matter how spontaneous these events may seem, there are groups or individuals who play a leadership role.

Whether we like it or not, the masses of workers express themselves through organizations, or at least through individuals who play the role of leaders after having won the confidence of their peers.

Even in a seemingly spontaneous movement, someone gives the speech that convinces their colleagues to go on strike at a general assembly. An organization or individual wrote the leaflet that gives workers arguments for a strike. An organization or individuals come up with the idea to occupy the workplace. All this does not come from nowhere.

Conversely, in the workers’ movement, organizations or individuals may also exercise their authority to put the brakes on a struggle. People or organizations may argue for an end to the strike. Some people will say that you can’t occupy a workplace because that would be a violation of the property rights of the bosses.

This battle of ideas and methods is not decided in advance. Not all workers draw the same conclusions at the same time. A minority will realize the necessity of a factory occupation, a general strike, etc., before the rest. In a revolution, a minority will understand that the possibility exists for workers to take control of the economy. Their job is to organize to convince the rest of the workers.

Even in a movement that seems spontaneous, organizations will eventually play a leading role.

As Trotsky explains in “The Class, the Party and the Leadership”:

History is a process of the class struggle. But classes do not bring their full weight to bear automatically and simultaneously. In the process of struggle the classes create various organs which play an important and independent role and are subject to deformations…Political leadership in the crucial moments of historical turns can become just as decisive a factor as is the role of the chief command during the critical moments of war. History is not an automatic process. Otherwise, why leaders? Why parties? Why programs? Why theoretical struggles?

The different tendencies of the workers’ movement express themselves through different organizations. Marxists, too, want to organize—and create a revolutionary party.

What is a revolutionary party?

The term “party” has a negative connotation among some layers of the labour movement and the youth. And for good reason! The existing political parties do everything to push these layers away. Even the so-called left-wing parties, once in power, bow to the dictates of the banks and do the dirty work of the capitalists, sometimes even more viciously than the right. This was the case with one of the most recent left governments, Syriza, in Greece in 2015.

When Marxists talk about the need for a revolutionary party, we do not have a parliamentary machine in mind. A party is first and foremost ideas, a program based on those ideas, methods to implement the program, and only then a structure, an organization that can spread the program throughout the movement and win people over.

As we have already explained, the tendency to organize is already present within the working class, leading to the formation of trade unions and parties. The different tendencies of the labour movement are expressed through different organizations or groupings.

Trade unions, by their very nature, aim to gather as many workers as possible. Who would propose that unions should include only revolutionary workers? These would be weak unions indeed. But a revolutionary party is composed differently from trade unions.

In “A Letter to a French Syndicalist about the Communist Party,” Trotsky explains:

How should this initiative group [the party] be composed? It is clear that it cannot be constituted by a professional or territorial grouping. It is not a question of metal workers, railway workers, nor advanced carpenters, but of the most conscious members of the proletariat of a whole country. They must group together, elaborate a well-defined program of action, cement their unity by a rigorous internal discipline, and thus assure themselves of a guiding influence on all the militant action of the working class, on all the organs of this class, and above all on the unions.

Not all layers of the working class and the youth draw the same conclusions at the same time. Some workers believe that capitalism is the best system. Others don’t like capitalism, but don’t believe it can be overthrown. Others are simply indifferent. But others come to the conclusion that the struggle for socialism is necessary. Having understood this, these people will necessarily want to steer the labour movement in that direction.

Naturally, the task of this socialist minority (what Trotsky calls “cadres”) will be to organize to win the confidence of the other layers of the working class in the struggle. This task will be all the more effective if this minority is grouped in an organization with a common program.

In “Discussion on the Transitional Program,” Trotsky explains:

Now, what is the party? In what does the cohesion consist? This cohesion is a common understanding of the events, of the tasks, and this common understanding – that is the program of the party. Just as modern workers more than the barbarian cannot work without tools so in the party the program is the instrument. Without the program every worker must improvise his tool, find improvised tools, and one contradicts another.

A program and organization need to be built in advance of a revolution, just like a worker’s tool should be made ahead of getting on with a given task.

The Spanish Revolution: a class without a party or leadership

What happens when there is no revolutionary leadership, when there is no revolutionary organization? Or when the organizations that do exist hold back the movement?

Trotsky’s “The Class, the Party and the Leadership” talks about the defeat of the Spanish revolution of 1931-39. This inspiring event is perhaps the most tragic example of what happens when a class does everything to overthrow capitalism while there is no revolutionary leadership, or when the organizations that exist refuse to take power.

The crisis of the 1930s hit Spain hard. The working class and peasants were crushed by overwhelming poverty. Landowners and capitalists (often the same individuals) had reduced living conditions to a miserable state in order to maintain profits. In 1931, faced with the rising anger of the masses, the ruling class was forced to sacrifice the monarchy and the Republic was proclaimed. But in itself, the transition to a democratic republic had done nothing to solve the problems of the working class and poor peasants.

In February 1936, after two years of right-wing government, the masses brought the Popular Front to power. This government was composed of socialists, communists, the POUM (a supposedly Marxist party, but which constantly oscillated between revolution and reformism) and even the anarchists who led the main trade union federation, the CNT. These workers’ organizations also included the bourgeois Republicans in the Popular Front. The presence of capitalist parties forced the government to moderate its program, to slow down reforms in favour of the peasants and workers, to leave bourgeois property intact. The Popular Front government even went so far as to repress the workers in struggle.

Without waiting for the reforms promised by the Popular Front, the workers implemented the 44-hour work week and wage increases on their own, and freed the political prisoners imprisoned under the previous right-wing government. Between February and July 1936, every major Spanish city saw at least one general strike. One million workers were on strike in early July 1936.

The workers’ movement was going too far for the capitalists. On July 17, 1936, General Francisco Franco began a fascist uprising, with the full support of Spanish industrialists and landowners. The goal was to overthrow the government, destroy the unions and workers’ parties, and build a strong government so that the capitalists could perpetuate the exploitation of the workers and peasants without their constant struggle. Faced with the fascist coup, the Popular Front parties refused to arm the workers to resist.

In spite of this, spontaneously, the workers did everything in their power to repel the fascists. They took sticks, kitchen knives and other weapons at hand, fraternized with soldiers, and invaded barracks to find real weapons. The workers built militias, which took the place of the bourgeois police. In addition to these measures of “military” defense against fascism, the workers took economic measures. In Catalonia, transportation and industries were almost completely in the hands of workers’ committees and factory committees. Next to the central government in Madrid and the government of Catalonia, a second power, that of the workers, was emerging.

But what happened then? The leadership of all organizations – the socialists, communists, the POUM, and the anarchist CNT – put a brake on the movement. In Catalonia, they participated in dismantling the workers’ committees. The socialists and communists were the vanguard in telling the workers to go home, not to seize the factories, and to let the bourgeois government lead the fight against fascism. The POUM tail-ended the other organizations, and entered the Catalan bourgeois government in the fall of 1936, sanctioning policies aimed at curbing the revolution.

Of particular interest is the attitude of the anarchist leaders of the CNT. During this period, the CNT even boasted that it could have taken power: “If we had wished to take power, we could have accomplished it in May [1937] with certainty. But we are against dictatorship.”

Because they were anarchists and therefore against power in general, the leaders of the CNT refused to consolidate the workers’ democracy that was being born. The opportunity was missed. But these same anarchists, who refused to take power in the name of the working class, were happy to join the bourgeois government of Catalonia! You cannot make this up.

The workers were completely demoralized. This tragic story ends with the victory of Franco and the fascists in the civil war of 1936-39.

Why was the Spanish Revolution defeated?

The workers spontaneously pushed back the fascists and took control of the workplaces, especially in Catalonia. The workers were moving in the right direction. But the leaders of the working class organizations all put a stop to the movement of the masses. As Trotsky explains in “The Class, the Party and the Leadership,” in such a situation it is not easy for the working class to overcome the conservatism of its leaders. An alternative must already exist:

One must understand exactly nothing in the sphere of the inter-relationships between the class and the party, between the masses and the leaders in order to repeat the hollow statement that the Spanish masses merely followed their leaders. The only thing that can be said is that the masses who sought at all times to blast their way to the correct road found it beyond their strength to produce in the very fire of battle a new leadership corresponding to the demands of the revolution. Before us is a profoundly dynamic process, with the various stages of the revolution shifting swiftly, with the leadership or various sections of the leadership quickly deserting to the side of the class enemy.

And later:

But even in cases where the old leadership has revealed its internal corruption, the class cannot improvise immediately a new leadership, especially if it has not inherited from the previous period strong revolutionary cadres capable of utilizing the collapse of the old leading party.

Not ancient history

The Spanish Revolution is far from an isolated example or one that belongs to the past.

As recently as 2019, a revolutionary wave swept through Latin America, North Africa and the Middle East. Chile, Ecuador, Colombia, Iraq, Lebanon, Algeria and Sudan all experienced general strikes, mass movements or revolutions. And everywhere, the same question of revolutionary leadership was posed, and its absence left its mark on events.

The case of Sudan is particularly striking. In December 2018, a mass movement broke out against the dictator Omar al-Bashir. Extreme poverty, IMF-imposed austerity, and massive unemployment drove the masses to the streets. A mass sit-in was even built by the revolutionaries in the capital, Khartoum.

An article in the Financial Times explained:

“One cannot know for sure what Russia felt like in 1917 as the tsar was being toppled, or France in 1871 in the heady, idealistic days of the short-lived Paris Commune. But it must have felt something like Khartoum in April 2019.”

This was a true revolution! In April, the ruling class was forced to remove the dictator. A Military Transitional Committee was formed to ensure that the army retained power.

The main organization behind the protests was the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA). This organization called for demonstrations, and even called for a general strike towards the end of May, to demand that the army relinquish power. This strike completely paralyzed the country.

In early June, the regime sent militias to suppress the Khartoum sit-in. Instead of scaring Sudanese workers, another general strike was organized by the SPA, paralyzing the country once again. Resistance committees were created.

Here we had a real opportunity for the workers to take power, to take control of the economy. But instead, the SPA called for an end to the strike. Then it negotiated an agreement with the military council for a three-year transition before holding elections. As a result, two years later, the army is still in power and the misery continues.

What was missing in Sudan? The workers went on two general strikes, held a sit-in despite the repression, and formed grassroots committees to organize the movement. The workers did everything they could. They could have taken power.

But the main organization that had authority among the masses compromised with the army rather than take power. As we have already explained, in such a situation you cannot invent a new organization on the spot.

Like it or not, leadership is a fact of life. One cannot escape the need to organize. While the workers’ movement is being led by the wrong leadership, while working class organizations are holding the movement back, the task at hand is to build an alternative in advance – a genuine revolutionary party.

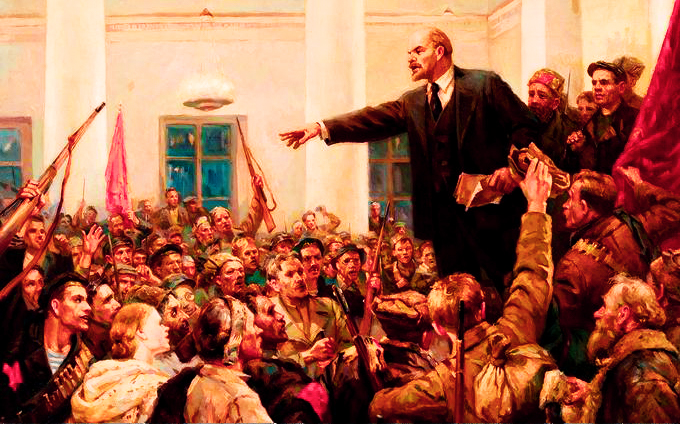

The Russian Revolution of 1917

In a discussion of the role of a revolutionary party, it is impossible to ignore the Russian Revolution of 1917.

It is not for nothing that Marxists devote so much time to the study of this revolution. For the first time in history, except for the brief episode of the Paris Commune of 1871, the workers and the oppressed took power, overthrew capitalism, and took the first steps toward establishing a workers’ democracy and a socialist society. To build the victories of the future, revolutionaries must study the victories of the past.

The victory of the Russian workers in October 1917 did not happen on its own.

In February 1917, the World War was ravaging Russia. The workers and peasants in uniform at the front no longer wanted to fight for another man’s cause. The workers in the factories and their families were starving. The status quo was no longer tenable. On the initiative of the women workers of Petrograd, the workers of the city went on strike, and after a week of mass mobilization, the tsar was forced to abdicate.

The Petrograd Soviet was then formed, and soviets mushroomed throughout Russia. The soviets were enlarged strike committees, which began to take control of the functioning of society. In fact, they held power in their hands.

But alongside the soviets, the bourgeoisie arranged for a provisional government to be formed, anxious to keep capitalism in place. This situation of “dual power” lasted until October.

Between February and October, through the ups and downs of the revolution, the provisional government demonstrated that it had no intention of satisfying the demands of the masses: peace, bread for the workers, and land for the peasants.

Within the soviets the reformist parties of the time, the Socialist-Revolutionaries (SRs) and the Mensheviks, had the confidence of the majority of the workers and peasants during the first months of the revolution, and used their position to make the soviets support the bourgeois provisional government. Their leaders even entered this government. The Mensheviks and SRs believed that it was “too early” for the working class to take power, that the bourgeoisie should be allowed to rule, and that the struggle for socialism would come later.

As the months went by, the Mensheviks and the SRs found themselves completely discredited in the eyes of the workers, the soldiers and the peasants. But thankfully, there was an alternative. It is towards the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin and Trotsky, that the masses turned. Having spent months patiently explaining that it was necessary and possible to take power from the hands of the bourgeoisie, and having won their confidence, the Bolsheviks were able to channel the immense energy and initiative of the masses towards victory in October 1917.

The Bolshevik Party and Lenin

With the Russian Revolution, for the first time in history, workers took power and managed to keep it. Why did they succeed where so many other movements have failed?

The explanation cannot be in the “maturity” of the Russian workers compared to the Spanish workers of the 1930s, for example. It is not that the Russian workers were more combative than the Spanish. Nor was it that the Russian workers were particularly more intelligent, or anything like that. The difference was the presence of the Bolshevik Party.

The Bolsheviks had not created the Russian Revolution. Although Bolshevik activists had played a role in February, the fighting mood of the masses had been created by capitalism, by the disastrous situation of the country. Trotsky explains this in his History of the Russian Revolution: “They accuse us of creating the mood of the masses; that is wrong, we only tried to formulate it.”

This is precisely the role of a Marxist organization: to formulate consciously what the workers come to understand in a semi-conscious or unconscious way.

But the Bolshevik party did not appear spontaneously in 1917. You can’t change the world overnight. Building a revolutionary party takes time and energy.

The Russian Marxists had begun their work in the 1880s and 1890s by creating small isolated groups that organized discussion circles on the basics of Marxism. The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) was created officially in 1898. The Bolshevik and Menshevik split occurred in 1903, where they became factions of the RSDLP. The Bolsheviks were implacable in their defence of Marxism, and parted ways for good with the Mensheviks in 1912, to become an independent party.

We sometimes hear today that the left should simply unite and put aside its differences. Why are there so many socialist or left-wing organizations, we are asked? Why does the IMT insist so much on Marxist theory? The reality is that if groups unite without really agreeing, it is a recipe for paralysis. Theoretical differences will come out on every important issue, and the “united” organization will not be able to move forward. A kayak with two people rowing in opposite directions will turn in circles, while a single person in a kayak will move forward.

Any political group must be based on some theory. This is one of the most valuable lessons of the history of Bolshevism. As Lenin explained as early as 1900:

Before we can unite, and in order that we may unite, we must first of all draw firm and definite lines of demarcation. Otherwise, our unity will be purely fictitious, it will conceal the prevailing confusion and binder its radical elimination. It is understandable, therefore, that we do not intend to make our publication a mere storehouse of various views. On the contrary, we shall conduct it in the spirit of a strictly defined tendency. This tendency can be expressed by the word Marxism.

For 20 years before the revolution, the Marxists of the Bolshevik party patiently built an organization based on a common program, educating activists in advance in the ideas of Marxism, with the aim of playing a leading role in the workers’ movement. The study of theory and history is essential for building a revolutionary organization today.

Left to their own devices, the Mensheviks and SRs would have led the revolution to defeat. Fortunately, there was an alternative with the Bolsheviks, who won over the workers during 1917, based on the very experience of the masses between February and October. This is what Trotsky explains in “The Class, the Party and the Leadership”:

Only gradually, only on the basis of their own experience through several stages can the broad layers of the masses become convinced that a new leadership is firmer, more reliable, more loyal than the old. To be sure, during a revolution, i.e., when events move swiftly, a weak party can quickly grow into a mighty one provided it lucidly understands the course of the revolution and possesses staunch cadres that do not become intoxicated with phrases and are not terrorized by persecution. But such a party must be available prior to the revolution inasmuch as the process of educating the cadres requires a considerable period of time and the revolution does not afford this time.

In Russia, this party existed ahead of time. There were 8,000 Bolsheviks in February 1917; by the time of the seizure of power in October, based on a correct political perspective, they had reached 250,000.

The role of leadership within the party

But how did the Bolsheviks come up with a correct political perspective? Is the party, in itself, sufficient?

The rise of the Bolsheviks to power was not a straight line. It is not a commonly known fact that between March and April 1917, the leaders at the head of the Bolshevik Party inside Russia at that time had no intention of fighting for power. With Lenin and Trotsky still trying to make their way from exile back to Russia, the main Bolshevik leaders present in Petrograd at that time were Stalin and Kamenev. Under their leadership, the Bolshevik newspaper, Pravda, essentially defended the policy of the Mensheviks: that it was “too early” for the workers to seize power.

Some rank-and-file activists in the Bolshevik party rejected these ideas. Being active on the ground, they saw that it was entirely possible and necessary for the workers to take power through the soviets. In fact, it was the soviets that ruled the country, but they still had to consolidate their power. But what could they answer to the argument that it was “too early” to take power?

As Trotsky explains in his History of the Russian Revolution: “These worker-revolutionists only lacked the theoretical resources to defend their position. But they were ready to respond to the first clear call.”

This call came with Lenin’s return to Russia in April 1917. At that moment, Lenin was categorical: the working class, allied with the poor peasantry, could take power through the soviets, and not only liberate the peasants, bring peace and bread to the workers, but begin the socialist tasks and start the international socialist revolution.

In April 1917, Lenin was the only leader of the Bolshevik party to defend this perspective (Trotsky had not yet arrived in Russia, and joined the party only in July). But due to his immense personal authority, and especially due to the fact that his policy corresponded to the experience of the Bolshevik militants at the base, Lenin succeeded in having his perspective adopted at the Bolshevik party conference held in late April. From that moment on, the Bolshevik Party, under Lenin’s leadership, set itself the goal of patiently explaining to the workers the necessity for the soviets to take power.

What would have happened if Lenin had not been able to reach Russia? In a revolution, time is a key factor. The Bolshevik leaders might have come to understand the need for soviet power, but there is no indication that they would have understood it while the workers were still mobilized. The working class cannot remain constantly in struggle. At some point, either the revolution wins, or doubt and apathy begin to set in. If Lenin had not intervened in 1917, the Bolshevik party leadership would most likely have missed the chance to take power. So it is not enough to have a party; that party must have a leadership that knows where it is going.

A victorious socialist revolution cannot be made without the participation of the working class. But this class must have a party. And that party must have a leadership that knows what it is doing. These three ingredients are the key to the success of future revolutions.

The role of the individual in history

Comparing Spain and Russia, one might ask: isn’t it mere luck that the Russian working class could count on an individual like Lenin? Wouldn’t it just have taken a Spanish Lenin, and everything would have been fine?

First of all, Lenin himself was not born Lenin: he was, in a certain sense, a creation of the Russian workers’ movement. Lenin was the result of the work of building a revolutionary party, which he had greatly contributed to building. Without the party, Lenin could not have disseminated his ideas in 1917 and played the role he did. But conversely, Lenin’s authority in his party came from the fact that he had spent nearly 25 years patiently building it.

Trotsky summarizes these ideas perfectly in “The Class, the Party and the Leadership”:

A colossal factor in the maturity of the Russian proletariat in February or March 1917 was Lenin. He did not fall from the skies. He personified the revolutionary tradition of the working class. For Lenin’s slogans to find their way to the masses there had to exist cadres, even though numerically small at the beginning; there had to exist the confidence of the cadres in the leadership, a confidence based on the entire experience of the past…The role and the responsibility of the leadership in a revolutionary epoch is colossal. [Emphasis added]

Similarly in the History of the Russian Revolution:

Lenin was not an accidental element in the historic development, but a product of the whole past of Russian history. He was embedded in it with deepest roots. Along with the vanguard of the workers, he had lived through their struggle in the course of the preceding quarter century…Lenin did not oppose the party from outside, but was himself its most complete expression. In educating it he had educated himself in it.

The revolutionary leadership provided by Lenin and the Bolsheviks did not come out of nowhere. It was the result of a quarter century of patient work in building an organization. In building the party, Lenin became Lenin. Thousands of other Bolsheviks, by building the party, also became leaders of the workers’ movement. This fact is summarized in the anecdote that in 1917, a single Bolshevik in a factory could win all his colleagues to the party program. This authority came from all the previous work of party building. Party building, dialectically, built these individuals who played a great role.

The Russian Revolution is a striking example of the role of the individual in history. The construction of a revolutionary organization, a collective endeavor, makes it possible to form individuals who can play a decisive role in the movement. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts; and building the whole strengthens the parts! We must learn from this for today, and repeat what the Bolsheviks did.

Tragically, a different fate awaited the great Marxist Rosa Luxemburg during the period of the Bolsheviks. While she spent her life fighting the reformist bureaucracy in the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), Luxemburg did not build an organized revolutionary faction in the party, as Lenin had done in the RSDLP with the Bolsheviks. It was not until 1916 that the Spartacist League was founded, which was more of a decentralized network than a revolutionary organization.

When the German Revolution broke out in November 1918, the League had little connection with the masses. In December, the League transformed itself into the Communist Party. However, from the outset, the party was permeated by a sectarianism that seriously handicapped it; party activists refused to work in the trade unions, and the party boycotted the elections to the National Assembly, which would have given it a chance to have a platform to spread its ideas. In this young communist party, Rosa Luxemburg opposed this ultra-leftism. But she did not have a group of cadres who understood the political situation as well as she did and who could carry her ideas. The Communist Party made one mistake after another.

In January 1919, the Social Democratic government provoked an uprising of the working class in Berlin in order to isolate and repress the advanced workers, and above all the Communist Party. The inexperience and weakness of the Communist Party’s influence over the workers, meant that they were unable to forestall the provocation. During those events, Luxemburg herself, along with the other outstanding leader, Karl Liebknecht, were murdered. Thus, the fact that Luxemburg did not build a revolutionary party in advance led to a tragic defeat and her own death, decapitating the leadership of the German working class. From then on until 1923, the Communist Party, deprived of the leadership of its two main figures, was unable to lead the German working class to power. The Russian and the German revolutions serve to underline the same point, although from two different angles: the vital need of a revolutionary leadership.

A few days before her assassination, Rosa Luxemburg drew conclusions from the first months of the German revolution. Her conclusion is far removed from the “spontaneism” that her alleged followers attribute to her:

The absence of leadership, the non-existence of a center responsible for organizing the Berlin working class, cannot continue. If the cause of the revolution is to advance, if the victory of the proletariat, if socialism is to be anything more than a dream, the revolutionary workers must set up leading organizations capable of guiding and using the fighting energy of the masses.

The leadership of the movement today

It is no secret that all over the world the Marxist movement has been thrown back for a whole historical period. The post-war boom laid the foundations for reformism in the West, while the fall of the Soviet Union was accompanied by an unprecedented ideological offensive against Marxism. The most pretentious, like Francis Fukuyama, even proclaimed the “end of history,” which would have found its achievement in liberal democracy.

The labour movement also experienced setbacks during the 1980s and 1990s, whereas the 1970s had been a time of mass movements and revolutions. It was during the following decades that the leadership of the labour movement shifted far to the right.

In Quebec, for example, it was in the 1980s that the FTQ, the province’s largest trade union central, stopped talking about “democratic socialism” and the second largest, the CSN, abandoned the anti-capitalist ideas expressed in the manifesto Ne comptons que sur nos propres moyens. Too often at the top of the labour movement today are leaders who collaborate with the bosses rather than mobilize their members. The current president of the CSN, for example, said for the 50th anniversary of the Conseil du patronat (the bosses’ union), the headquarters of the Quebec bourgeoisie: “We sometimes clash and have different points of view, but we get along very well when it comes to promoting employment, fostering good working conditions and ensuring Quebec’s economic growth.” This is far from an isolated example. This is the state of the leadership of the labour movement today.

In the labour movement, one of the main attacks on Marxists is the caricature according to which we say that if there were a revolutionary leadership, then the workers would always be in struggle, always ready for action. According to these people, we criticize the union leaders as if it were possible for the leaders to magically bring about mass movements.

This idea is a complete caricature of the Marxist analysis of the relationship between the working class and its leadership.

As we have already explained, workers are not constantly in struggle. Revolutions are historical exceptions that inevitably arise from the class struggle itself. But what happens before a revolution? What should be the role of the leadership of the labour movement when the situation is not revolutionary—that is, most of the time?

At the risk of sounding repetitive, the working class is not homogeneous. Until the day of the revolution, there will be apathetic layers, skeptical layers, while others will want to fight against the attacks of the bosses. The contradictory and heterogeneous character of class consciousness is a fact that we have no choice but to deal with.

Union leaders do not have the power to magically bring about a movement. But the role that a good leadership can play in the class struggle is to prepare the rank-and-file, establish a plan of action, and educate the union members in order to bring about a mass movement. No, it is not possible to magically organize a movement. But yes, it is possible to educate workers about the need for this or that demand, for this or that method of struggle.

An excellent example of what good political leadership can accomplish can be found in the 2012 student strike in Quebec. In 2010, the Quebec Liberal government hinted that tuition fees would be raised. Already, student activists were beginning to organize. In March 2011, the 75 per cent tuition increase was officially announced, to be implemented in the fall of 2012.

The leadership of ASSÉ, the most radical student union at the time, spent the year 2011 educating the students about what the increase in tuition meant, mobilizing students with the conscious plan to organize an unlimited general strike. Some ASSÉ activists, many of whom had anarchist tendencies, would certainly not like the terms “leadership” or “leaders” attached to them, but you can’t change reality by changing the name—they were most certainly playing a leadership role, and a good one at that!

With the conscious plan to organize the strike, and because these methods of struggle were what the movement needed in the face of an inflexible government, the ASSÉ leadership organized the largest student strike in North American history.

Playing a leadership role is in no way contradictory to full grassroots participation. On the contrary—it was because the ASSÉ leadership provided direction, educating thousands of activists on the need to fight the hike, that it unleashed the fighting spirit and creativity of the hundreds of thousands of students involved in the movement across Quebec.

The example of the student strike shows the role of good leadership. Showing the way forward creates the conditions for thousands of people to actively participate in the struggle. To be sure, the ASSÉ leaders did make some mistakes. In the summer of 2012, when the Liberals announced the holding of an election, they refused to support Québec solidaire, the only main party supporting free education, and basically ignored the election, while most students ended the strike to fight to kick out the Liberals. We have analyzed the whole process elsewhere. But this mistake doesn’t take away from the main lesson: the need for leadership.

The question of leadership is a burning issue in the workers’ movement and in the trade unions around the world. How often do we hear that workers supposedly do not want to struggle? That you can’t organize a strike by snapping your fingers? In Quebec, public sector unions have been in negotiations for over a year. The right-wing CAQ government won’t budge and is offering ridiculous conditions to its workers. While some teachers’ unions are moving towards an all-out strike, other teachers’ unions have voted on five-day mandates only, to be implemented “at the appropriate time.” We have criticized this situation elsewhere. In a public meeting organized by Labour Fightback in Quebec, a local president of one of these unions with a five-day strike mandate explained his view of the role of the union leadership thus:

It’s not on us [the union leadership] to decide [on a strike], it’s on our members, and they can decide if we inform them…at the FSE [the union] we could have called for the all-out strike, but in the ‘plateaux’ [union locals] I don’t see any delegates saying ‘Let’s go, all-out strike’… We have to share information, we’re puppets when we’re union [leaders], we’re not the ones who have to tell people what to do… In my local general assembly, if someone would come and say ‘I want an all-out strike,’ I’d like that, I think I would burst with joy.

The logic here is one that is found throughout the movement, taken to the extreme. According to this logic, if workers are not talking about an all-out strike, it is not the job of union leaders to propose it. This logic is a self-fulfilling prophecy: if the leaders don’t do anything and don’t propose a bold solution to the members (which is deemed “telling people what to do”), then it is normal that workers don’t have confidence that we can fight and win, and won’t propose militant ways of fighting themselves!

We are not saying that you can organize a mass movement by snapping your fingers. But what we are saying is that the role of union leaders is to provide leadership, not just to be an information office and wait for the members themselves to come to radical conclusions. The union leadership needs to set a plan, educate the membership, give them confidence, and thereby create the conditions for the membership to be prepared to take the road of uncompromising class struggle – just like the student movement leadership did in 2012.

Building a socialist leadership for the movement

Right now, the labour movement is led by people who believe in the capitalist system, and who don’t believe it can be overthrown. Union leaders have become detached from the conditions of the workers. They prefer the status quo to fighting the bosses. They are skeptical and do not believe in the creativity and fighting spirit of their members.

The current leadership of the labour movement will increasingly come into conflict with the reality of capitalism. Austerity will very soon be on the order of the day. Capitalism will show itself more and more for what it really is: horror without end for working people. We are already starting to see this with COVID-19.

But what will happen if the leaders of the labour movement allow workers to be attacked and do nothing? They will be discredited in the eyes of the workers they are supposed to represent. Trotsky explains how this process develops:

A leadership is shaped in the process of clashes between the different classes or the friction between the different layers within a given class. Having once arisen, the leadership invariably arises above its class and thereby becomes predisposed to the pressure and influence of other classes. The proletariat may “tolerate” for a long time a leadership that has already suffered a complete inner degeneration but has not as yet had the opportunity to express this degeneration amid great events. A great historic shock is necessary to reveal sharply the contradiction between the leadership and the class.

COVID-19 and the economic crisis that is just beginning are one of these historic shocks. All over the world, the anger of the masses is building up. The workers are suffering from unemployment, from the reduction of their living and working conditions, while the rich are amassing fortunes that are rising day by day. As we are entering an epoch of revolutions all over the world, the leadership of the workers’ movement is still stuck in the past.

So what can socialists do?

In a recent piece entitled “Socialist Leaders Won’t Save the Unions,” an activist with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) states:

People think that leadership is a matter of having the sash and the tiara, that by virtue of getting elected to a position, you have all this credibility, and everybody’s going to listen to you—and it’s simply not true.

You need to actually, simply organize the floor. And it’s not that you can’t do it as a union officer, but it[‘s] also not the case that being a union officer contributes to it.

In a sense, we agree with our anarcho-syndicalist comrades. They are attacking a tendency for individual socialists to parachute themselves into leading positions in a union with no base in the rank-and-file to enact militant socialist policies. There are numerous instances of good activists taking shortcuts only to get isolated in leadership structures and swallowed up by the bureaucracy. Marxist are totally opposed to taking leadership positions without first building a base.

But this dichotomy between grassroots organizing and union leadership is fundamentally flawed and only sees one half of the problem. In fact, many reformist union leaders would agree with the idea that elected leaders can’t organize at the grassroots, because it absolves them from having to act! Moreover, mobilizing at the base is itself an act of leadership—it means leading your colleagues toward a certain course of action. But once you’ve organized at the base, what happens next? What if the people in union leadership positions seek to actively disorganize the floor? They will need to be prevented from doing so. How? If you are not prepared to replace these people with union leaders that want to fight, this means leaving control in the hands of the bad leaders. Whether we like it or not, we come back to the need for good leadership in the movement, for counterposing militant class fighters to union leaders that are detached from the workers.

What, therefore, is the role of socialists in the labour movement? We say that, yes, we must organize among the rank-and-file, defend methods of class struggle, educate the workers on the need to fight capitalism. And on this basis, we can gain the confidence and authority of other workers to take leadership positions in the unions, and lead the movement. And the best way to do that is to be in the same revolutionary organization.

The reality is that there are some individuals on union executives who call themselves socialists in Quebec, and they are indeed not “saving the unions.” The problem is that they are isolated, they don’t have an organization that allows them to really apply socialist policies against the resistance of other leaders of the movement who don’t want to fight. To have real weight in the movement, it is necessary to unite in the same organization those who have understood the necessity of socialism.

History has shown more than once, and not just in the labour movement as such, what happens to socialist or radical individuals who do not build a revolutionary organization. Inevitably, these people will capitulate to the existing organizations. For example, Angela Davis, a highly respected former communist activist, long ago gave up on the idea of building a revolutionary party. She ended up supporting the Democratic Party and Joe Biden in the last election. The same goes for the anarchist Noam Chomsky or the supposedly-Marxist academic David Harvey. Politics is done through organizations. When you don’t build an alternative, you will inevitably fall for the “lesser evil” of what exists.

Revolutionary optimism

Class consciousness is something that develops very quickly. How many participants in the 2012 student struggle knew nothing about tuition hikes just months before the strike? How many of these students were apathetic and disinterested before a campaign was waged to prepare for the movement? The same questions could be asked of every mass movement or revolution. Consciousness is conservative, but has the potential to become radical and revolutionary.

Skeptics base themselves on the weak side of the working class, on its apathetic and demoralized layers, and conclude that a revolution is not possible. Marxists, on the contrary, base themselves on the immense revolutionary potential of our class.

No, the workers are not always ready to lead a revolution. But by fighting now for socialist ideas to gain authority in the workers’ movement, we can contribute to a victorious revolution when the masses move.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, unprecedented misery is setting in for millions of workers everywhere. But out of this chaos is emerging a new generation of young people who want to fight against the capitalist system.

The wonderful mass movement in the US triggered by the murder of George Floyd has shown that even the greatest imperialist power cannot escape the rising anger. The conditions are being created for revolutionary movements all over the world. It is on this potential that the unshakable revolutionary optimism of the Marxists is based.

The socialist revolution will not happen automatically. It requires activists to consciously defend a socialist program within the movement. As an isolated socialist activist, you can accomplish nothing. But united under a common banner, with a common program and common ideas, we can have an infinitely greater impact than any individual activist can have. By joining a revolutionary organization, you build yourself up and help build others. By joining a revolutionary organization, you build an alternative to existing organizations that lead the working class from defeat to defeat, instead of accepting them and capitulating to them. By joining a revolutionary organization, you help bring the ideas of Marxism to the working class in a way no individual can do on their own. This is what the International Marxist Tendency offers to workers and youth. We invite you to join this project which is bigger than all of us.

We will leave the last word to Trotsky, who left us these inspiring lines a few months before his assassination:

The capitalist world has no way out, unless a prolonged death agony is so considered. It is necessary to prepare for long years, if not decades, of war, uprisings, brief interludes of truce, new wars, and new uprisings. A young revolutionary party must base itself on this perspective. History will provide it with enough opportunities and possibilities to test itself, to accumulate experience, and to mature. The swifter the ranks of the vanguard are fused the more the epoch of bloody convulsions will be shortened, the less destruction will our planet suffer. But the great historical problem will not be solved in any case until a revolutionary party stands at the head of the proletariat The question of tempos and time intervals is of enormous importance; but it alters neither the general historical perspective nor the direction of our policy. The conclusion is a simple one: it is necessary to carry on the work of educating and organizing the proletarian vanguard with tenfold energy.