Wellred Books’ bestselling title The Classics of Marxism: Volume One is available in a brand new edition. Here we publish the introduction by Fred Weston – leading member of the Revolutionary Communist International. Fred highlights how, far from being relics of the past, the writings inside by Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky are the most modern texts you can come across if you want to understand the nature of the capitalist system and how it can be overthrown.

This collection is therefore an indispensable tool kit for anyone serious about changing the world.

Get your copy of The Classics of Marxism: Volume One here!

We are living through the most turbulent period in the history of capitalism.

Poverty levels are growing everywhere, while at the same time a small minority, the ‘1 per cent’, are accumulating unprecedented quantities of wealth. Working conditions are worsening everywhere as workers’ rights are being whittled away by the bosses. Wages are not keeping up with inflation and benefits for the poor are being constantly cut. Housing has become a big issue with house prices sky-rocketing, while at the same time rent is becoming unaffordable for many workers. On top of all this, climate change is having catastrophic effects in many countries, from flooding to wildfires, with drought destroying the livelihoods of millions of people.

In these conditions, the imperialist powers are in conflict with each other over markets and spheres of influence, meddling in the affairs of every nation on the planet, producing instability and turmoil, wars and civil wars. This is leading millions, if not billions, of people in all countries to ask themselves why this is happening, what are the causes and what are the solutions.

All this, in turn, is producing political volatility, with big shifts in voting patterns as people abandon the old established parties in search of something new that can offer them a way out of the present impasse. This explains the rise and fall of parties, and the emergence of new formations, with forces that seemed marginal and insignificant suddenly surging in the polls.

Some people seek solace in religion, looking for the answers to the present nightmare in the Bible or the Quran, or in the myriad of other religions. The four texts published in this volume do not provide the solace of religion. Marxists believe that the material world can be understood, that the reasons for economic crises can be found in the mechanisms of capitalism itself.

Marxism is first and foremost a philosophical and a scientific outlook which leads to an understanding that the capitalist system has reached its limits and needs to be removed. It also leads us to understand that humanity is capable of transforming the world, of ending class divisions and moving to a higher form of society. But to achieve that we need to first understand the nature of capitalist society. And to understand, one needs a scientific method.

By studying the four texts published here, The Communist Manifesto, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, The State and Revolution, and The Transitional Programme, you will be embarking on a road that leads to a Marxist understanding of society, which is the tool necessary for anyone who wishes to see an end to the present crisis facing humanity.

It has always been in the interests of the propertied class, of the rich, the privileged and the powerful, to combat those ideas that challenge their position in society. Throughout history all revolutionary thought has been subject to campaigns of falsification, denial and vilification. Marxism has suffered this onslaught since its very early days, both in the form of outright state repression, and the more subtle form of propaganda that attempts to distort its real meaning.

The worst kind of such falsification is that of those who present themselves as the ‘genuine interpreters’. It is therefore much better to read the original. The only sure way of grasping the basic ideas of Marxism is to read the fundamental texts of the great Marxist teachers of the past, starting with Karl Marx himself, together with his comrade in struggle Friedrich Engels.

The Communist Manifesto

The first text presented here is The Communist Manifesto, written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as a public statement of the principles and programme of the Communist League.

The Communist League was founded in June 1847, at a congress in London. It was formed as the result of a merger between the League of the Just, a secret society of German workers based in a number of European countries, and the Communist Correspondence Committee, which had been founded by Marx and Engels in Brussels.

Engels attended the League’s first congress as a delegate, and was instrumental in drawing up the statutes of the organisation, which declared:

“The aim of the League is the overthrow of the bourgeoisie, the rule of the proletariat, the abolition of the old, bourgeois society based on class antagonisms and the foundation of a new society without classes and without private property.”[1]

The League held a second congress in London in November-December 1847, which was attended by both Marx and Engels. Following a lengthy discussion on the principles of the League they were commissioned by the congress to draft a manifesto, The Communist Manifesto, which was eventually published in February 1848.

One may wonder what relevance does a text written around 180 years ago have for the new generations. And yet, if you read it, you will find that it accurately describes the world as it is today. One quote from Chapter One serves to demonstrate the relevance of this text for the situation we are facing in the present epoch:

“Modern bourgeois society, with its relations of production, of exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells. […] It is enough to mention the commercial crises that by their periodical return put the existence of the entire bourgeois society on its trial, each time more threateningly. In these crises, a great part not only of the existing products, but also of the previously created productive forces, are periodically destroyed. In these crises, there breaks out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity – the epidemic of overproduction.” [2]

The text goes on to explain that it is the very development of the productive forces in the hands of the private owners, the capitalists, that in turn undermine the system itself and “bring disorder into the whole of bourgeois society”. This opens up periods of crises:

“And how does the bourgeoisie get over these crises? On the one hand by enforced destruction of a mass of productive forces; on the other, by the conquest of new markets, and by the more thorough exploitation of the old ones. That is to say, by paving the way for more extensive and more destructive crises, and by diminishing the means whereby crises are prevented.” [3]

The outbreak of the First World War was the first sign that capitalism had reached a breaking point. The world market could not accommodate all the powers and the only way out for the capitalists was to go to war. The deep slump of the 1930s was a further confirmation of everything Marx and Engels had explained back in 1848.

The solution to that crisis was the unprecedented death and destruction of the Second World War. When the laws that govern the market no longer sufficed to settle conflicts between the major capitalist powers, war between them became inevitable.

Having laid waste to whole countries, the material conditions were created for reconstruction and the post-war economic upswing (1948-73). This was a period in which illusions in capitalism were strengthened. Such was the development of the productive forces, with all the social reforms that this allowed – from free healthcare and education, to relatively secure jobs and reasonable wages – that the idea that a revolutionary overthrow of the system was necessary seemed to have lost its relevance.

This explains why the ideas of reformism, i.e. that it is possible to gradually improve the living conditions of working people without revolution, were strengthened. It also explains the dominance in all countries of leaders in the labour movement who professed these ideas.

Genuine revolutionary Marxism was inevitably isolated in that period. But as Marx had explained, that same period was preparing the way for a new crisis of the system. That came in the early 1970s, with the first worldwide slump of the capitalist economy since the Second World War.

With the crisis came a tidal wave of class struggle that swept the world. How did the capitalist class recover from that period? On the one hand, in the same way as they did at the end of the first and second world wars, by using the reformist leaders of the working class – the leaders of both the trade unions and the mass political parties of the working class – to channel the class struggle down safe lines. The authority of these leaders had been strengthened during the post-war upswing of 1948-73, and they were able to exploit this to hold back and stifle the class struggle.

They appealed to the working class to accept temporary sacrifices in order to get back to the ‘good old days’ of the economic upswing, reassuring workers that this was the only way to solve the crisis of the system. They thus proceeded to implement austerity measures that the bosses were demanding. This was later followed by a wave of privatisations, while at the same time hugely expanding credit to stimulate consumption, and thereby the market.

This seemed to be working for a period, but as a consequence debt began to reach unsustainable levels, and thus we saw how this diminished “the means whereby crises are prevented”, leading to the 2008 financial crisis. History has now come full circle, and we are once again in the midst of a deep crisis of the system.

The Communist Manifesto also predicted that capitalism, having emerged in a few countries, such as Britain, would spread to every corner of the world, as we can see in these words:

“The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation. The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilisation into their midst, i.e. to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.”[4]

This describes exactly what we have seen in capitalist development since the days of Karl Marx. The ever-growing concentration of wealth in the hands of a few billionaires, while billions live in poverty, confirms another of Marx’s predictions about the concentration of capital.

This process is clearly evident in the most powerful capitalist country on the planet, the United States, where the top 10 per cent of households own more than two-thirds of the country’s wealth. This concentration significantly increased over the last few decades, and continues to do so. Globally, the top five corporations earn more than the poorest 2 billion people in the world.

Conversely, the share of global wealth going to workers in the form of wages has been falling systematically for years. Since 1980, the workers have lost between 6 and 8 per cent, around $6 trillion a year, and the levels of poverty worldwide have been growing. According to a 2024 report from the World Bank Group, 8.5 per cent of the world population lives in extreme poverty, while around 3.5 billion people, or 44 per cent of the global population, live on less than $6.85 per day. [5]

Marx and Engels, however, also pointed out that what the bourgeoisie produces, “above all, are its own grave diggers” and that “its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable”.[6] The number of metalworkers today has risen above the figure of 400 million globally. And if one includes all wage-workers, then the grave-diggers of capitalism today are counted in their billions. The working class has never been so strong both numerically and in terms of its specific weight in society.

These figures – and there are many more – serve to underline the fact that the analysis developed in the pages of The Communist Manifesto is as relevant, if not more relevant, today as when it was first written.

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific

The strength of Marxism lies in its method of analysis, in its philosophical outlook, defined as ‘dialectical materialism’. Marxists analyse the real concrete world, the real developments in society, in economics, in politics, in world relations and ultimately in the class struggle that flows from all of this. Marxism, however, does not limit itself to looking at the surface of phenomena, but looks more deeply at the inner contradictions that drive events.

If one were to limit oneself merely to an empirical observation of the immediate moment, one would lose sight of the more long-term processes that are developing. Instead, by looking at phenomena in their development, in their movement, seeing how they are changing and how they can change in the future, we can develop a perspective of where society is going and an understanding of the explosive events that are inevitable in the coming period. And, more importantly, we can prepare to intervene in them.

The second text included in this volume is a very good introduction to this dialectical method. It is based on Engels’ famous book Anti-Dühring, which, in a polemical manner, deals with the fundamental ideas of Marxism. Three chapters from that book were selected and arranged by Engels himself for publication as a shorter, more accessible text, and first published in French in 1880 as Socialism: Utopian and Scientific.

The reference to both utopian and scientific socialism encapsulates the essence of the text. Prior to Marx and Engels and the elaboration of their scientific method, there had been many socialists, such as Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier and Robert Owen, for whom, Engels explains:

“To all these, socialism is the expression of absolute truth, reason and justice, and has only to be discovered to conquer all the world by virtue of its own power. And as an absolute truth is independent of time, space, and of the historical development of man, it is a mere accident when and where it is discovered. With all this, absolute truth, reason, and justice are different with the founder of each different school.” [7]

For these utopian socialists all that was required was to seek the truth, to establish the ‘kingdom of reason’, without having to take into account the real concrete development of society. The utopians had many great ideas and identified the problems of capitalism quite clearly, but none of them fully understood the role of the working class, and all were opposed to the seizure of power by the workers.

Saint-Simon appealed to the capitalists to provide for the proletariat in order to avoid class struggle and revolution; Fourier told everyone to set up socialist colonies and therefore remove themselves from the class struggle; the Owenites were actually opposed to the Chartist movement and tried to compete with it, because they only looked at the economic question, and put forward various schemes to liberate the workers without the seizure of power. As Engels states:

“Not one of them appears as a representative of the interests of that proletariat which historical development had, in the meantime, produced.”[8]

Marxism moved away from such thinking and placed the idea of socialism on a sound materialist basis, i.e. that it would come about as a result of the class struggle within capitalist society, and not just as some abstract ideal conquering the minds of all of humanity. This mode of thinking flows from an understanding of the real material world, not in a mechanical but in a dialectical manner.

Engels, in praising the great discoveries of science and human thought of the previous four centuries, explained that the method of investigation that had been thus developed:

“… has also left us as legacy the habit of observing natural objects and processes in isolation, apart from their connection with the vast whole; of observing them in repose, not in motion; as constraints, not as essentially variables; in their death, not in their life.” [9]

So-called ‘common sense’ looks at things in a static, lifeless manner – but this can only go so far in explaining more complex phenomena. To move to a deeper, more insightful mode of investigation, dialectical thinking is required.

Engels explains that his and Marx’s dialectical method derived from the great German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. But he also adds that:

“Hegel was an idealist. To him, the thoughts within his brain were not the more or less abstract pictures of actual things and processes, but, conversely, things and their evolution were only the realised pictures of the ‘Idea’, existing somewhere from eternity before the world was.”[10]

To transform dialectics into a tool for understanding the world we live in, a return to materialism was required, not to the mechanical materialism of the eighteenth century, but to a higher form, i.e. dialectical materialism, which analyses phenomena in their motion, in their processes of change, which flow from their inner contradictions. As Engels explains:

“… the old idealist conception of history […] knew nothing of class struggles based upon economic interests, knew nothing of economic interests; production and all economic relations appeared in it only as incidental, subordinate elements in the ‘history of civilisation’.

“The new facts made imperative a new examination of all past history. Then it was seen that all past history, with the exception of its primitive stages, was the history of class struggles; that these warring classes of society are always the products of the modes of production and of exchange – in a word, of the economic conditions of their time; that the economic structure of society always furnishes the real basis, starting from which we can alone work out the ultimate explanation of the whole superstructure of juridical and political institutions as well as of the religious, philosophical, and other ideas of a given historical period. […]

“From that time forward, socialism was no longer an accidental discovery of this or that ingenious brain, but the necessary outcome of the struggle between two historically developed classes – the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. Its task was no longer to manufacture a system of society as perfect as possible, but to examine the historico-economic succession of events from which these classes and their antagonism had of necessity sprung, and to discover in the economic conditions thus created the means of ending the conflict.”[11]

Herein we have the great contribution of Marx and Engels to the socialist movement. Socialism was no longer an abstract ideal removed from the real material conditions of any given society, but it now became a historical necessity, the final inevitable outcome of the class struggle itself. And these conclusions flowed, on the one hand, from the application of dialectical thinking to the development of society, and on the other from the emergence of capitalist production and with it the proletariat, the class to which the task of transforming society now fell.

A study of this text will give the reader a basic grasp of the method of Marxism and prepare them for tackling other important works of the great Marxists, and thus learn to apply the method to the analysis of today’s turbulent world.

The State and Revolution

This important work of Marxist theory was written by Lenin, the leading theoretician of the Bolshevik Party, between August and September of 1917. Basing himself on extensive quotations from Marx and Engels, Lenin presents a comprehensive and authoritative Marxist analysis of the state.

The question of the state was the most pressing issue in the revolutionary events then unfolding. The revolution in Russia had broken out in February 1917 and the workers had quickly forced the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II. Following the example of the 1905 Russian Revolution, the workers and soldiers set up soviets – workers’ councils – organs that had the potential to become the foundations of a workers’ state.

Initially, however, the leadership of the soviets was dominated by the reformist ‘socialist’ parties – the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries (SRs), who, failing to understand the significance of the soviets as organs of workers’ power, handed power to the bourgeoisie, who formed the Provisional Government.

The Provisional Government was unable to solve the problems that had led to the revolution: the devastating conditions created by the First World War, the poverty afflicting workers in the cities, and the key question of the land, which left millions of peasants under the domination of the landlords. In these conditions, the clash of irreconcilable class interests meant the Provisional Government was inevitably unstable. In an attempt to overcome this, the Menshevik and SR leaders were brought into the cabinet.

However, things continued to move on, and as the masses began to see through the limitations of that government, the influence of the Bolsheviks started to grow rapidly. At the beginning of July, Petrograd (St. Petersburg) saw a series of mass demonstrations, which raised the Bolshevik slogan of ‘All Power to the Soviets!’ The Provisional Government ordered military cadets, Cossacks and counter-revolutionary units from the front line to fire on the crowd. This was followed by a campaign of slander against Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

The government shut down the Bolshevik’s papers and issued for Lenin’s arrest, forcing him into hiding in Finland. The soviets, led by the reformists, became mere appendages to the Provisional Government. The illusions of the reformist leaders in the bourgeois state risked derailing the revolution, and opened up the possibility of brutal reaction being unleashed on the workers and peasants. That is why Lenin, in the heat of the revolution, felt it was an urgent task to make clear to the ranks of his own party, and of the wider working class, the Marxist position on the state.

The full title of this work, The State and Revolution: The Marxist Theory of the State and the Tasks of the Proletariat in the Revolution, makes it clear that this was an urgent question in the events that were unfolding. It was the clarity of the Bolsheviks on the question of the state that allowed them to lead the working class to seize and hold on to power in October 1917.

Any serious revolutionary organisation that takes upon itself the task of transforming society – of ending capitalist society and replacing it with socialism, a system that places the interests of the working class first and foremost – also has to understand the monster we are up against. That is why an understanding of what the capitalist state really is, is absolutely essential.

People in general do not fully understand the real nature of the state. It is in the interests of the ruling class – of the capitalists who own the means of production and enormously benefit from this materially – to obfuscate the true nature of the state and its historical roots in the early forms of class society.

Engels, in his classic text, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, developed the idea that the state arose as the instrument of the ruling propertied classes to oppress those below them, the producers of the wealth, whether they be slaves, serfs or proletarians. This could only arise once private property had emerged out of a long process in which human labour was able to produce a surplus.

Instead of this scientific understanding, the state today is presented as an impartial and neutral arbiter standing above the classes. The reformists in the labour movement – of both the left and right varieties – share these illusions and help to promote them.

They do not see – or refuse to see – that the real essence of the state is its special bodies of armed men – of the police, the judiciary and all the other bodies – that are there not to mediate between the classes, but to serve the interests of one class in society, which in the present epoch is the capitalist class. Already in The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels explained that the “executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.”[12]

Marx also dealt with this question in later writings, in particular in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. He also drew the conclusion from the experience of the Paris Commune in 1871 that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made State machinery and wield it for its own purposes.”[13]

It is this basic position that Lenin elaborates on in The State and Revolution. The ideas of Marx and Engels on this key question had been distorted and falsified by the revisionists within the movement. In particular, the Right wing of the German Social Democracy had attempted to misquote, or take out of context, this or that phrase of both Marx and Engels to justify their own opportunist (i.e. reformist) interpretation of the Marxist position on the state: that it was an instrument to ‘reconcile’ the interests of two classes, rather than the instrument of one class to dominate the other.

Since Lenin wrote this classic of Marxist literature, the reformists within the labour movement have gone much further in promoting the illusion that the state stands above classes, that it is ‘neutral’ when it comes to class questions. This confirms the absolute need to continually study and defend Marxist theory, against the repetition of isolated phrases, which can be used to justify anything.

Marxism is a revolutionary theory, epitomised by its dialectical method. Many times in history, parties purporting to be ‘Marxist’ have used a caricature of the ideas to cover their opportunism, which serves to confuse workers and discredit Marxism itself.

It is not a coincidence that Lenin set himself to writing a theoretical defence of genuine Marxism on the central question of the state during the revolutionary events in Russia – in August-September 1917. And it is no coincidence that it was Lenin who succeeded in leading the working class to power and beginning the socialist transformation of society. Without a clear understanding of the nature of the bourgeois state, this would not have been possible.

That is why Lenin states early in his text:

“… in view of the unprecedently widespread distortion of Marxism, our prime task is to re-establish what Marx really taught on the subject of the state.”[14]

He stated clearly that:

“The state is a product and a manifestation of the irreconcilability of class antagonisms. The state arises where, when and in so far as class antagonisms objectively cannot be reconciled. And, conversely, the existence of the state proves that the class antagonisms are irreconcilable.” [15]

Lenin quotes at length from both Engels and Marx so as to make absolutely clear where they stood on this question. He meticulously establishes the fundamental ideas of Marxism on the question of the nature of the state.

Having established the basic idea that the bourgeois state cannot be used by the working class – that it needs to be smashed – he turns to the question of what is to replace it. It is here that he polemicises with the anarchists. He starts by pointing out that Marxists agree with them on the need to smash the bourgeois state, but disagree on what comes next, on what form workers’ rule will take.

Lenin poses clearly the need for a ‘workers’ state’ to replace the bourgeois state. It would be utterly utopian to believe that one could pass seamlessly from a class society to a classless one. The bourgeois class, the capitalists who own the means of production, are not going to willingly give up their property and all the privileges that come with it. That is why they have such an elaborate state apparatus, together with the ‘armed bodies of men’.

And that is why the working class, in taking over the means of production and running them in a planned and rational manner in the interests of all working people, must have its own state. It would be the instrument through which workers’ rule could be guaranteed, through which the old propertied classes would be blocked from taking back control over the means of production.

Lenin was also fully aware of the danger of bureaucratisation within such a state in the early period of its existence. That is why he stressed that the working class needs a state to expropriate the capitalists and plan the economy, but this “must be exercised not by a state of bureaucrats, but by a state of armed workers.”[16]

To guarantee that such a process would unfold, some basic conditions for workers’ democracy would be required, and these can be summed up as:

- Free and democratic elections with the right of recall of all officials.

- No official to receive a higher wage than a skilled worker.

- No standing army or police force, but the armed people.

- Gradually, all the administrative tasks to be done in turn by all – “so that all may become ‘bureaucrats’ for a time and that, therefore, nobody may be able to become a ‘bureaucrat’.”[17]

Such a state would be of a very different nature to all previously known states in history. For the first time, it would be a state that represents the overwhelming majority of society, not a privileged minority. In that sense, it would be more of a semi-state to govern over the period of transition from capitalism to communism, to assure the definitive and final burial of the old system based on class divisions, and once that has been achieved there would no longer be any need for a coercive state apparatus. As Lenin pointed out:

“The state withers away in so far as there are no longer any capitalists, any classes, and, consequently, no class can be suppressed.”[18]

However, he also added that:

“For the state to wither away completely, complete communism is necessary.”[19]

And he concludes:

“Then the door will be thrown wide open for the transition from the first phase of communist society to its higher phase, and with it to the complete withering away of the state.”[20]

By this what is meant is that society will have achieved such a development of the productive forces, and the workers will have reached such a high level in their ability to administer things, that all class distinctions would have come to an end, and with them the need for a state.

The State and Revolution was one of the most important works that Lenin wrote. In it he provides the definitive Marxist explanation on the question, and all class-conscious workers and youth should read this text, study it and absorb its lessons if they wish to take part in the successful removal of the capitalist system and understand what needs to take its place.

The Transitional Programme

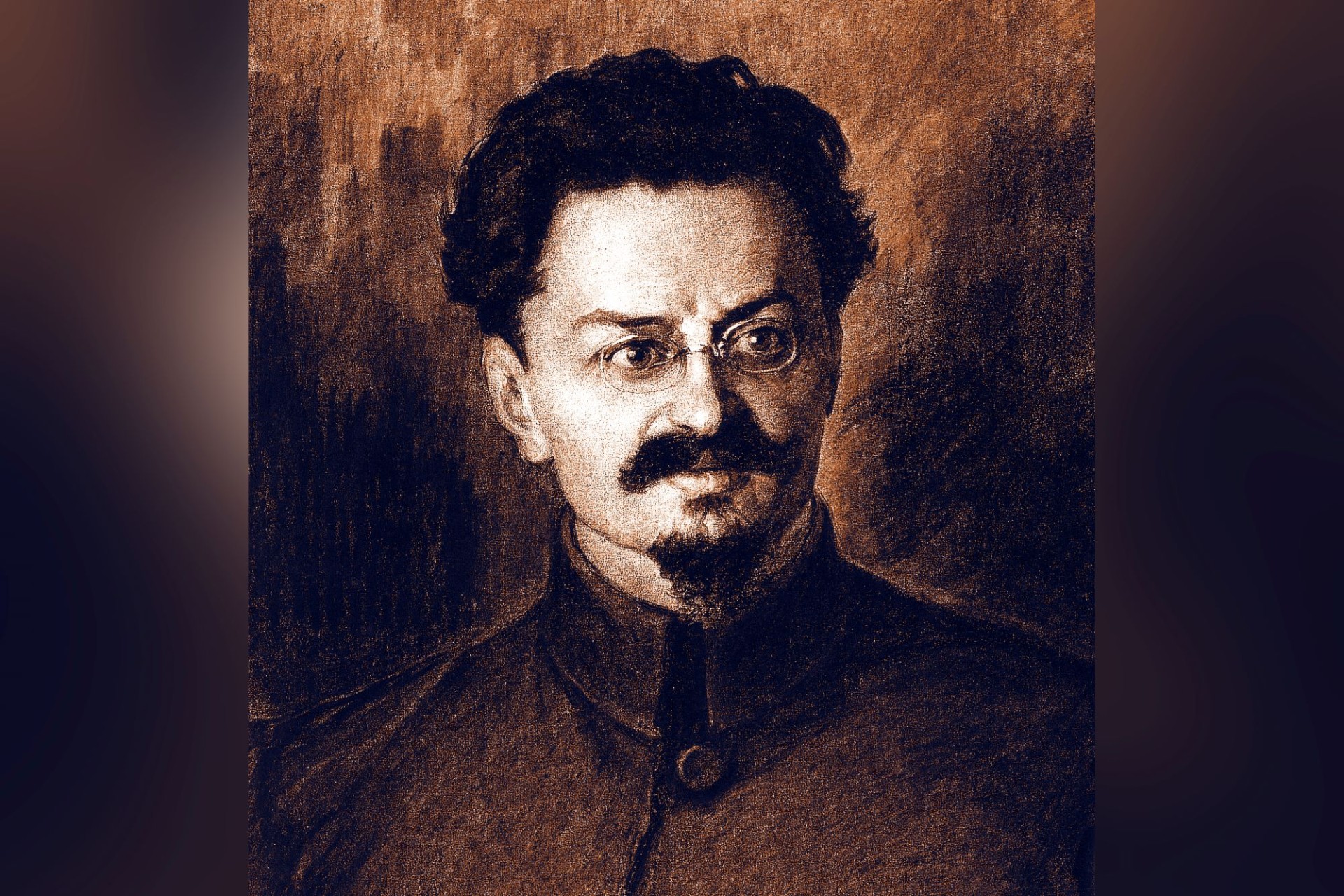

Finally, what is the programme that revolutionary communists fight for? How do we connect it to the day-to-day struggles of the working class? This is very skilfully dealt with by Leon Trotsky in The Transitional Programme, written in 1938 and adopted by the first congress of the newly formed Fourth International in 1938. Why was it necessary to build a new International?

Along with Lenin, Trotsky led the Bolshevik Party and the working-class to power in the October Revolution of 1917. Both Lenin and Trotsky understood that it was not possible to build socialism in one country, especially in the extremely backward conditions of Russia at the time. That is why they consciously worked to spread the revolution internationally.

The old Second International had degenerated into a number of reformist parties who had betrayed the working class by supporting their own ruling classes during the First World War. Lenin and Trotsky worked assiduously for the establishment of the Third International, which would become known as the Communist International, or ‘Comintern’. Its national sections, the various Communist Parties, were created to provide the working class with the necessary revolutionary leadership in each country.

Unfortunately, in one revolution after another, starting with the German Revolution of 1918, the Communist Parties proved to be either too weak to influence events, or theoretically unprepared for the great tasks that faced them. These defeats led to the isolation of the Soviet Union. This, combined with Russia’s economic backwards, exacerbated by the devastation of the Russian Civil War, led to the gradual degeneration of the Soviet Republic, with power being usurped by a privileged bureaucracy, headed by Stalin.

After Lenin’s death in 1924, this process began to accelerate rapidly. In these conditions, Trotsky formed the Left Opposition, which advocated a return to the ideals of the October Revolution, to the genuine workers’ democracy of the early years after 1917. A struggle ensued between the rising bureaucracy and the supporters of the Left Opposition. Trotsky was finally expelled from the Politburo in 1926 and exiled in 1928.

The Comintern, having failed to lead the revolutionary movement in one country after another, was transformed by degrees from an instrument of world revolution to an instrument of the foreign policy of the ruling bureaucracy of the Soviet Union.

A key turning point came with the victory of Hitler in 1933. The German Communist Party and the Comintern leadership failed to understand the nature of fascism, even seeing in the rise of the Nazis the preparation of conditions which would have allowed the Communists to take power, rather than the total crushing of the German working class, which was its true essence. This allowed Hitler to come to power and liquidate one of the strongest workers’ movements in the world without firing a shot.

In any healthy international, such a catastrophic defeat would have provoked intense debate and internal struggle. And yet, throughout the Comintern the false line of the bureaucracy was accepted with almost no resistance. Trotsky thus proclaimed that the Comintern was dead as a truly revolutionary organisation and declared that a Fourth International had to be built.

What is remarkable about this document is that – as in the case of The Communist Manifesto – it seems even more relevant today than when it was written.

Its opening statement: “The world political situation as a whole is chiefly characterised by a historical crisis of the leadership of the proletariat”, aptly describes the impasse facing the whole of the international workers’ movement in the present epoch.[21]

The level of degeneracy of the labour and trade union leaders of today is unprecedented. This has left the working class leaderless, and also explains why right-wing, populist demagogues are able to gain traction and appear as if they are speaking for the workers. The responsibility for this lies on the shoulders of the so-called ‘leaders’ of the working class.

Everywhere, the reformist leadership of the working class has completely capitulated to the capitalist order. In Britain, the Labour leaders have become a mere appendage to the liberal bourgeois establishment, loyally serving the interests of the capitalist class. The same is true of the Social-Democratic leaders in Germany, and the ex-Stalinists in Italy who dissolved the Communist Party into what has become the Democratic Party, whose leadership is thoroughly bourgeois in its thinking and programme. In the United States, the trade union leaders are tied hand and foot to their own ruling class. The same situation can be seen in one country after another.

Trotsky’s text also seems to be describing the crisis facing capitalism today:

“Mankind’s productive forces stagnate. Already new inventions and improvements fail to raise the level of material wealth. Conjunctural crises under the conditions of the social crisis of the whole capitalist system inflict ever heavier deprivations and sufferings upon the masses. Growing unemployment, in its turn, deepens the financial crisis of the state and undermines the unstable monetary systems.”[22]

And again:

“The bourgeoisie itself sees no way out. […] it now toboggans with closed eyes toward an economic and military catastrophe.”[23]

At that time he warned that:

“Without a socialist revolution, in the next historical period at that, a catastrophe threatens the whole culture of mankind.”[24]

That catastrophe came in the form of the Second World War, with its 55 million dead, with the horrors of the Holocaust, and the generalised destruction that afflicted many countries. Today we are not facing a world war in the immediate period, but we have many local and regional wars, civil wars and armed insurgencies, terrorist attacks, etc., afflicting many parts of the world.

We can say that the present crisis of world capitalism presents us once again with the prospect of either socialism or barbarism. The elements of barbarism are already present in the wars and civil wars, in the famines that regularly affect different parts of the world, in the growing poverty, and with it violence and crime. We have also seen the potential for socialism in the mass class struggles and revolutions in many countries, from the Arab Spring of 2011, to the revolutionary upheavals in Sri Lanka (2023), Bangladesh (2024), and many more.

The question of questions is: how can such mass movements be directed towards the successful overthrow of capitalism through socialist revolution, how can the programme of revolutionary communists become the programme of the masses? This was at the heart of The Transitional Programme.

In a discussion he held with the leaders of the American Trotskyists in March 1938, Trotsky explained that the aim was:

“… not to engage in abstract formulas, but to develop a concrete programme of action and demands in the sense that this transitional programme issues from the conditions of capitalist society today, but immediately leads over the limits of capitalism. […] These demands are transitory because they lead from the capitalist society to the proletarian revolution, a consequence in so far as they become the demands of the masses as the proletarian government. We can’t stop only with the day-to-day demands of the proletariat. We must give the most backward workers some concrete slogan that corresponds to their needs and that leads dialectically to the conquest of power.”[25]

The essential idea is that the revolutionary party must start from the immediate problems facing the working class, from such questions as inflation, low wages, long working hours, expensive housing costs, healthcare costs, education, and so on. However, it must not stop there. To do so would mean transforming the programme into the classic ‘minimum programme’ of the old Second International, which was disconnected from the ‘maximum programme’ of socialism. This would drag us down into the swamp of reformism.

No, the revolutionary party has the duty to start from the immediate problems, raise demands that offer a solution, but always link these to the need for the working class to take power as the means of concretising those same demands. We have to understand that the overthrow of capitalism through socialist revolution cannot be accomplished by a small organisation isolated from the mass of working people. It can only be carried out by the masses themselves.

As Marx explained, “the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves”.[26] He also explained that “theory also becomes a material force as soon as it has gripped the masses”.[27]

The working class is the class that can transform society, but it needs a clear understanding of the tasks before it. The working class also does not reach revolutionary conclusions overnight. The working class enters into struggle over its immediate demands in the workplace, and that is where revolutionary communists must start from.

We do not, however, limit ourselves solely to such demands; we participate shoulder-to-shoulder with the workers in their struggles, but we always raise the idea that in the long run it is capitalism that is the obstacle to them achieving a permanent solution to their problems.

The final victory of the socialist revolution would be unimaginable without the day-to-day struggles of the working class under capitalism. It is through such struggles that the working class begins to understand the true nature of the system they are up against. Over time, and through many experiences, the workers begin to understand that this or that reform, this or that conquest, such as higher wages or a shorter working week, cannot be maintained without removing the capitalist system as a whole.

Revolutionary communists do not adopt a sectarian or ultra-left stance on such questions. What this means is that they do not stand aloof from the mass of working people, they do not belittle their lack of understanding of the need for social revolution and for the overthrow of the capitalist system. They understand that the mass of working-class people learn from experience.

They therefore participate in the day-to-day struggles of the workers, going through the experience of their struggles, and at each stage they base themselves on the conclusions the workers are drawing and use these to raise the general level of understanding. At the same time, they do not sow any illusions in the system, but expose it in the eyes of the masses.

The Transitional Programme has demands that apply to different situations, taking into account the concrete conditions in each country. It has demands that apply to the conditions in developed capitalist countries, to industrialised countries, where workers are concentrated in large factories. It also raises demands for those countries where industry is less developed and a large part of the population still lives in rural, peasant conditions. It raises specific demands that apply to fascist regimes, where democratic slogans could play a role in mobilising the masses.

It also has a section dedicated to the Soviet Union, where the Stalinist bureaucracy had usurped political power. Trotsky raised the need for ‘political revolution’, i.e. a revolution that maintained the conquests of October 1917 – a centralised planned economy – while reconquering power for the working class as the only means of moving society forward to genuine communism.

The essence of transitional demands lies in their immediate relevance to the problems of the working class. Faced with rampant inflation, the call for a sliding scale of wages answers the immediate problem of the falling value of wages. The call for a sliding scale of hours – or for a shorter working week, as we would pose it today – with no cut in wages, answers the problem of unemployment: if there aren’t enough jobs, then share the work out so all have jobs.

However, they do not stop at the immediate problems, but are linked to the fact that if such demands are to be won and maintained, then the working class must pose itself the task of overthrowing the whole system through socialist revolution.

Moving beyond reformism

For many decades the illusion that gradual reform of the capitalist system was possible dominated the working-class movement. This, however, has now started to break down. After the financial crisis of 2008, we saw austerity measures imposed on the working class, as the capitalist class sought to bring down the unprecedented levels of debt that had built up over the previous period.

The impact of these policies can be summed up in one statistic: since 2009, the austerity measures applied across the European Union have left the average citizen of Europe 3,000 worse off in terms of real purchasing power. Everywhere, real disposable incomes have been drastically cut. The pressure is relentless. It has been calculated that for the EU member states to achieve a government debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 per cent – as established in a treaty they all signed up to – would require an annual cut of 2 per cent of public spending every year until 2070.

This implies permanent austerity measures for two or three generations to come. It means not only significant falls in the real purchasing power of wages, but also destroying healthcare, education, social housing, pensions, etc., i.e. everything that makes for a civilised existence.

The first reaction to this was seen in the period starting around 2014-15. This was the period of the emergence of new political forces such as Podemos in Spain, the rise in popularity of formerly marginal parties such as SYRIZA in Greece, the radical shift to the left in the British Labour Party which saw Jeremy Corbyn becoming the party leader, while in the United States a figure like Bernie Sanders, with all his talk about “a political revolution” against “the billionaire class”, became very popular.

Unfortunately, in one way or another, these figures massively disappointed the millions of workers and youth who looked to them. In Greece, the SYRIZA leaders formed the government and proceeded to carry out the very same policies the masses had voted against. In Spain, Podemos entered coalition governments that carried out the same policies. Corbyn, faced with a systematic onslaught from the Right wing of the Labour Party, failed to fight back. In the US, Sanders completely capitulated to the Democratic Party establishment.

This led to widespread disappointment, but also led to a layer, particularly among the youth, seeking answers as to why all this had happened. This explains the rise in popularity of the idea of communism among a significant layer, in particular among the youth.

In spite of all the propaganda of the mainstream media aimed at promoting the idea that communism is dead, that Marxism is a thing of the past with no relevance to the world of today, a huge layer of the youth see capitalism as the problem, and they seek an understanding of why society is in the impasse that it finds itself in.

It is in this context that many workers and youth are turning to the only rational and scientific explanation of the present crisis – the ideas of scientific socialism, of Marxism. In spite of all attempts to prove that capitalism is the only possible form of society we can live in, it is capitalism in crisis that is pushing the most advanced thinking layer of the youth and the working class to seek a revolutionary way out. And it is these layers that will find the answers they are looking for in the present publication.

A careful reading and study of the four texts presented in this volume is essential for every young worker, for every young student, for all workers who have drawn the conclusion that society is at an impasse, that there is something fundamentally wrong with the system as a whole.

Karl Marx famously said that “philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”[28] Here he was not dismissing philosophy as such. Marxism is also a philosophical outlook. What Marx meant was that we do not limit ourselves to interpreting and analysing the world, but we engage actively in fighting to change it. That is the essence of revolutionary communism.

Fred Weston,

March 2025

References

[1] ‘Rules of the Communist League’, December 1877, Marx and Engels Collected Works (henceforth referred to as MECW), Vol. 6, p. 633.

[2] In this volume, p. 10.

[3] Ibid., p. 11.

[4] Ibid., p. 8.

[5] World Bank Group, ‘Poverty, Prosperity and Planet Report’, 2024.

[6] In this volume, p. 17.

[7] Ibid., p. 59.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., p. 62.

[10] Ibid., p. 66.

[11] Ibid., p. 68, emphasis in original.

[12] Ibid., p. 7.

[13] Marx, ‘The Civil War in France’, MECW, Vol. 22, Lawrence & Wishart, 1975, p. 328.

[14] In this volume, p. 99, emphasis in original.

[15] Ibid., p. 100, emphasis in original.

[16] Ibid., p. 193, emphasis in original.

[17] Ibid., p. 206, emphasis in original.

[18] Ibid., p. 190, emphasis in original.

[19] Ibid., emphasis in original.

[20] Ibid., p. 198, emphasis in original.

[21] Ibid., p. 223.

[22] Ibid.

[24] Ibid., p. 224.

[25] Trotsky, ‘On the Labour Party Question in the United States’, March 1938 (available at: marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1938/04/lp.htm).

[26] Marx, ‘Provisional Rules of the Association’, October 1864, MECW, Vol. 20, p. 14.

[27] Marx, ‘Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law’, December 1843 – January 1844, MECW, Vol. 3, p. 182.

[28] Marx, ‘Theses on Feuerbach’, 1845, MECW, Vol. 5, p. 5, emphasis in original.