After a month-long strike in the winter of 2024, postal workers were ordered back to work by the federal government. This is not unfamiliar territory—in fact, the union has had its democratic right to strike taken away every single time it has tried to exercise it since 1981.

But what many people may not know is that the CUPW finds its origins in the 1965 wildcat strike which defied the law and won. This was the largest illegal strike of government employees in Canadian history, and it won collective bargaining rights for all federal public sector employees.

Public sector wage-slaves

The Canadian economy grew by leaps and bounds during the post-war boom. However, this wealth did not trickle down to the workers. In fact, the John Diefenbaker Progressive Conservative government froze public sector wages in 1959 and 1962. While Lester Pearson promised wage increases and collective bargaining rights when he won the election in 1963, in typical Liberal fashion he dragged his feet and by 1965 had failed to deliver.

Postal workers, like all public sector employees at the time, did not have the right to strike. They were not even allowed to negotiate a contract and wages were determined directly by the treasury board. As a result, wages and working conditions were deplorable.

This was especially the case at the post office, where mail volumes had doubled in 10 years. Instead of hiring more workers, management simply pressed the workers harder, increasing the intensity of labour. For example, a work measurement scheme was implemented, imposing quotas of letters sorted per minute. Letter carriers were often forced to work 12 hour days without overtime pay.

Postal workers were therefore both overworked and underpaid.

This wasn’t just a problem of wages and benefits, but also the brutal regime imposed on postal workers by the management. In his autobiography, CUPW leader Jean-Claude Parrot describes the prison-like working conditions at mail sorting facilities. Management-staffed “observation galleries” complete with one-way mirrors were placed all over the building, including in the washrooms! Parrot mentions it was known that “some inspectors exchanged jokes about the particular (bathroom) habits of some workers”.

Women had only been brought on in recent years as a new layer of part-time employees. Unsurprisingly, they got the worst of it. According to one worker:

“Supervisors blatantly fondled women, they’d walk along behind them, and those who let them sweet talk them or touch them would receive better treatment (…) If some supervisor didn’t like the fact that he was rejected last night, she wasn’t there tomorrow night, and that went on all the time. And if they raised any complaints, you were gone. And the post office didn’t have to answer to anybody if they fired you. They could fire you at the drop of a hat.”

Workers against their ‘leaders’

The daily humiliation the workers were forced to endure, compounded with exhaustion from overwork and abysmally low pay, created a powder keg waiting to explode. As postal worker Mattie Stockwell described it, “When we were delivering welfare cheques that were larger than our take home pay cheques, we thought that something had to be done.” Expressed in the language of Marxist philosophy, there was a quantitative build up that would eventually lead to a qualitative shift.

The spark that ignited the explosion was a new nationwide directive given by management. The directive forbade mail sorters to sit down for the first hour and a half of shifts, as well as after meal breaks. Parrot described the resulting outrage felt on the shop floor:

“This national directive was seen by workers as yet another demonstration of how someone in an Ottawa office, with no understanding of how and why sorting is done in a certain way, could be as stupid as the directive itself.”

Postal workers did have a union—of sorts. The Canadian Postal Employees Association (CPEA) and the Federal Association of Letter Carriers (FALC) represented mail sorters and deliverers at the time. These two associations had come together to form the Postal Workers Brotherhood (PWB) in order to bargain jointly with the government over a wage increase in June 1965.

But in reality, the FALC and the CPEA were not really unions. These “associations” served as tools of management to keep the anger of the workers within safe channels. Mattie Stockwell described the situation:

“In many cases, the people who were presidents of the association at the time, this was their means to promote themselves within the post office. If you had been president of the local… the next step was the supervisor. So they didn’t want to rock the boat too much.”

At the time, a government commission was investigating whether to grant public sector workers the legal right to strike. Two years in, it had yet to deliver a decision. As time dragged on, the situation became untenable for the rank-and-file postal workers who were getting impatient. The unavoidable conclusion that many were inevitably drawing was that they were going to take matters into their own hands.

But the leadership of the FALC and CPEA were focused on containing the anger of their members. As postal worker Alec Power described it:

“There was lots of outrage. And when one or two of us would pipe up, in respect to have to take to … the streets, they were outraged. They would corner you after a meeting and say ‘we can’t do that, we’ll all get fired and blah blah blah.’”

Today the leadership of the unions have adopted a similar attitude when faced with the routine use of back-to-work legislation. Any time a worker suggests defying back-to-work legislation, a similar hue and cry about “fines” and legal consequences is raised by the leadership to contain the members.

As a result, the leaders of many unions today have backed themselves into a corner. When push comes to shove, a class conflict is resolved by force. If the workers are able to shut down operations, then the employer will be forced to concede to the demands of the workers. Without the ability to strike, workers essentially lose all of their collective power. Flowing from this, employers then have no reason to give any concessions to the workers. The union leaders have made themselves powerless.

Alec Power, a rank-and-file postal worker in Toronto, described the conundrum that the leaders of the postal workers associations of 1965 found themselves in, “They couldn’t effectively represent because they had no power behind them. You know, what could they use as a lever? Obviously for working men this was the withdrawal of our labour.”

The strike

Despite the efforts of their leadership, the anger of the workers could not be contained any longer.

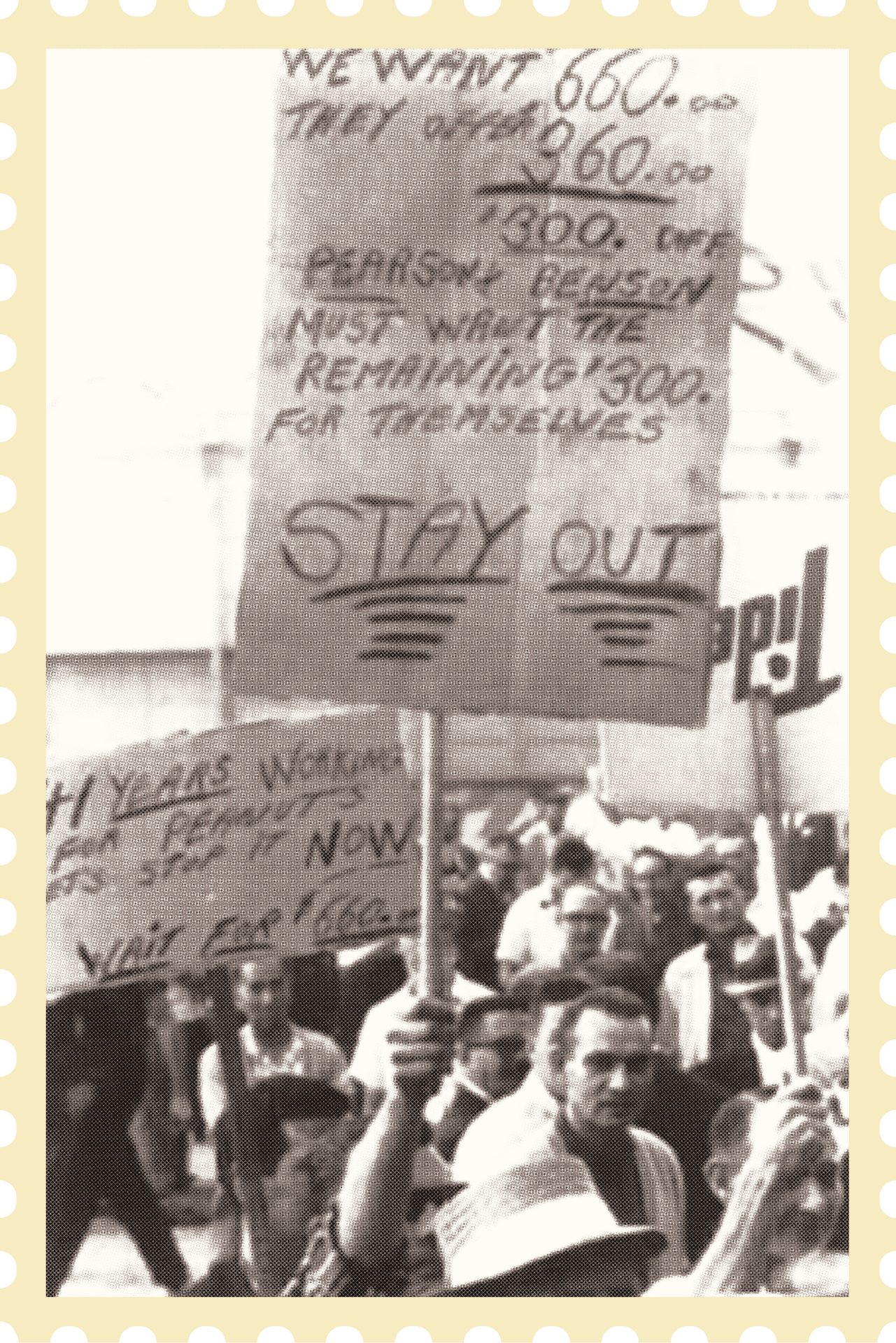

It was in Montreal where it all began. What was initially billed as an “information meeting” was transformed by angry postal workers. By the end of the meeting the workers resolved to go on strike for a $660 annual wage increase (the equivalent of $6,500 adjusted for inflation).

On July 14, a delegation went to Ottawa to try to convince the national leadership to support the strike. But the national leaders vehemently opposed strike action and would not even allow a vote to be held.

After being rebuffed by the national leadership, local leaders Willie Houle and Roger Decarie reached out directly to other locals. The result was that in the early morning hours of July 22, posties in Hamilton, Vancouver and Montreal walked off the job. With these three locals leading by example, it didn’t take long for others to follow suit.

Once they saw the bold lead being given, the strike spread like wildfire among the 22,000 postal workers across the country. As one postal worker from Windsor explained, “All of a sudden, the boys decided that if so many post offices were walking out across the country, we had to go and the boys just went.”

But all over the country, conservative ‘leaders’ in the associations tried to hold back the flood gates. For example, the local executive in Toronto was vehemently opposed to joining the strike. But rank-and-file postal workers were inspired and couldn’t be restrained.

Posties flooded a Toronto membership meeting and overwhelmed these so-called “leaders.”

Letter carrier Wayne Black correctly argued, “The government won’t give you anything, unless you show that you are not afraid to go out on strike.” Alec Power and Jimmy Brown, another rank-and-file postal worker, led the charge to take over the meeting and the workers voted to join the strike!

In response, the President of Toronto Letter carriers stated “They should all be thrown in jail,” while the President of the Toronto mail clerks Al Pinney crossed picket lines.

At its peak, 80 per cent of the membership of both associations were out on the picket lines in cities across the country.

Postal worker Jill Davidson captured the situation well when she said that the “impossible was taking place” and that the workers “had lost the fear of their own shadows.”

The heroism of these workers is simply astounding. They overcame the conservatism of their own leaders and launched a nationwide strike. The fact that there was no strike fund meant that the workers were accepting a complete loss of pay. But as one worker commented “maybe you lose money on the strike days, but you gain a lot in self-confidence and self-assurance of the fact that what you did was for you and for other people to follow you. Yes, you do gain, you gain your own self-respect.”

From having no previous tradition of striking, these workers had come a long way, defying the law that kept them down.

At the end of the day the law is but a piece of paper. Once the workers moved into action, all of the threats of the government amounted to nothing.

Government tries to conciliate

Faced with this unprecedented strike, the government changed its tactics and tried to reconcile with the workers. Lester Pearson went on the news stating that “In my opinion, the postal employees have a just claim.” He formed a commission headed by judge Anderson to review the issues surrounding the strike and come up with a recommendation.

But the workers weren’t going to go back easily. As Alec Power explained, “Our point wasn’t to get a review. It was to get the pay increases we had asked for in the beginning.”

The commission came forward and offered a wage increase of $360 a year. But the workers could feel their power. As Roger Decarie explained, “For the first time in its history, the federal government has opened negotiations with its employees. If it makes one offer, it will be willing to make another.”

But the government refused to budge, stating that “There will be no departure from the recommendations of judge Anderson, so far as the government is concerned.” And once again, they relied on the union leaders to try to corral the workers. As Vancouver strike leader Bill Kay describes, “The Postal Workers Brotherhood leadership and the Canadian Labour Congress leaned very very heavily on the strike leadership, to try to get us back to work.”

Montreal stands alone

The PWB were doing everything in their power to put an end to the strike. Now that they had a wage increase, they felt that it would be simple enough to convince the workers to go back.

But the rank and file postal workers in Montreal unanimously rejected this deal and decided to stay out.

The PWB leaders then traveled to Toronto and Vancouver to press their case to meetings of the striking workers. Not wanting to lose these votes, they scandalously forged a telegram bearing the names of the Montreal local leadership, saying that a decision had been made to go back to work!

Not wanting to stay out alone, the strikers in Toronto and Vancouver voted to call off the strike. Once Houle and the other Montreal leaders found out about this forgery, they publicly repudiated it—but the damage had already been done.

The Montreal workers were now isolated. However, in heroic fashion they refused to throw in the towel.

The government attempted to return to intimidation tactics. President of the Treasury Board Edgar J. Benson even went so far as to threaten to send in the army to break the strike. Still, the posties refused to back down.

When a spokesperson from the prime minister’s office hinted that the Montreal posties would all be fired, Houle shot back stating, “We don’t talk to ghosts. Let the prime minister say it himself.”

The pressure of the strike split the Canadian Labour Congress, with the Quebec branch coming out in support of the postal workers. Quebec Federation of Labour (FTQ, the Quebec branch of the CLC) leader Louis Laberge stated:

“If just one employee should suffer reprisal as a result of the strike, I promise that the combined might of the Quebec Federation of Labour and the Canadian Labour Congress will not only shake the federal government but will bring it down.”

In the end, the government upped its wage offer to $550, and Montreal strikers accepted. While the issue of working conditions was punted to a commission, and the $550 was $110 short of what they had been demanding, this none-the-less represented a significant victory which was only gained through a titanic struggle.

A new union forged in the heat of struggle

The 1965 postal workers strike represents a watershed moment in the Canadian class struggle. Some of the most underpaid workers with next to no rights had risen up against their own leaders and won significant gains.

Most importantly, the posties had conquered the right to strike. By 1967 this right was extended to the entire federal service.

The workers had come out of the darkness and created a new tradition. Within months, the leadership of the old organizations were voted out and an entirely new union was created: the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW). Bill Kay, the leader of the strike in Vancouver, defeated three members of the outgoing executive and became the new national president.

Forged out of the heat of the struggle, CUPW became one of the most militant, democratic unions in the country. They led many strikes that won important advancements, not just for postal workers, but all working class people. Most significantly, after a 42 day strike in 1981, CUPW won 17 months of maternity leave for postal workers. This formed the blueprint for the struggle for paid parental leave across the country.

Lessons for today

With capitalism’s decay accelerating before our eyes, it is more important than ever that we learn the lessons from the 1965 postal workers strike. The postwar order is collapsing and with it the material basis that allowed the creation of the welfare state in Canada. Capitalism can no longer afford the reforms of the past, and if we want to maintain them we will have to fight like hell.

This could not be more clear than in the case of Canada Post where the management have unleashed an all-out offensive against workers. Reacting to market pressures, they are attempting to Amazonify working conditions in order to compete with Jeff Bezos and private sector delivery giants in the capitalist race to the bottom. Just like in the years leading up to 1965, this represents an attempt to squeeze the workers and increase the intensity of labour. And the results will be the same.

Today, posties technically have the right to strike. However, each time CUPW embarks on a strike, the federal government, whether Liberal or Conservative, swoops in to override that right.

But posties are radicalizing and looking to take matters into their own hands, just as they were in 1965. This was shown by the fact that CUPW locals in Edmonton, Saskatoon, Moose Jaw and Burnaby all voted to defy the back-to-work order last fall.

And just like in 1965, the leadership of the postal workers leaves a lot to be desired. Since Jean-Claude Parrot—who was not afraid to risk it all and get arrested—led the union in the 1970s, the leadership has increasingly stifled the militant spirit of the rank-and-file.

This was the case last year when the federal government, without a debate or vote in the parliament, took away the right to strike from the postal workers. Even though there was widespread evidence that the ranks were ready to defy this order, the leadership of CUPW buckled and ordered them back to work. In fact, not unlike the strike breaking leaders of the CPEA-FALC who conspired with the leaders of the CLC to make sure their affiliate unions did not show solidarity with the postal workers, the national leadership of CUPW contacted the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), instructing them to stop their members from participating in cross picketing against the back-to-work order at a Vancouver plant last fall.

The situation requires that we go back to the initial impulse that gave birth to CUPW. The experience of 1965 showed exactly how the mass of postal workers could assert their will against a leadership determined to deny it. These lessons could not be more relevant for postal workers today. They only require a new generation of militants to take them up to continue the struggle to victory.

This is why the Revolutionary Communist Party organizes the CUPW Communists—a militant, revolutionary faction of communist posties. Our comrades are fighting to revive these militant traditions, and end the cycle of defeats which is repeated every time we enter negotiations.

Our right to strike is not negotiable. It was never something granted to us by the government or the constitution. It is something that our forebearers fought for with great sacrifice and won. And it is something that we must prepare to fight for again—not in the courts, but in the real world, on the picket lines. This is the only way to effectively fight back against this onslaught by management and the capitalist class as a whole.