The internet is full of articles and videos with titles like: Is cinema ever coming back? Is streaming going to ruin music? Can great art exist anymore? People talk about the epidemic of flat, gray-coloured movies; songs with nothing but a catchy hook clearly designed to go viral on TikTok; and the new phenomenon of “two-screen content” —Netflix shows designed to be listened to while one scrolls social media.

Interacting with the types of mass media that define culture today—music, film, and TV—feels like wading through slop, as this type of soulless, profit-maximizing “art” has been aptly named online. We’re left to wonder: who wants this? Who is it for?

Some, particularly academics, claim that the masses do want slop! We’re mindless consumers, addicted to empty stimulation and terrified of new ideas.

But in reality, there are real, objective economic dynamics behind what is happening to our culture, and why the art forms that colour the lives of billions are being degraded.

The media has been dominated by massive corporations who only want to give us more of what has turned a profit in the past, locking these art forms into a state of stagnation and repetitiveness.

They are hostile to art which dares to experiment, to express genuine emotion, or to strive toward the truth—in other words, they are hostile to the very essence of art itself. This has had a disastrous effect on music and film in particular, two of the art forms that play the biggest roles in the lives of everyday people.

From Renaissance to reboot

If we look at Western film, the last wave of innovation came with the “Hollywood Renaissance” which peaked in the 70s.

This was an exceptional period in which the creative vision of individual directors actually proved more profitable than traditional studio films. Visionaries like Stanley Kubrick and Martin Scorsese exploded in popularity, becoming known for their particular styles. Films felt original, innovative, and exciting. To be a movie-goer at this time was to be a part of something; a cultural phenomenon.

But the rejuvenation of Hollywood planted the seeds of its decline. The “Hollywood Renaissance” proved that movies could make serious money, and big corporations wanted in. The early 1980s saw large corporate takeovers of film studios, and at the same time, some experimental films flopped, while blockbusters like Jaws and Star Wars made a killing.

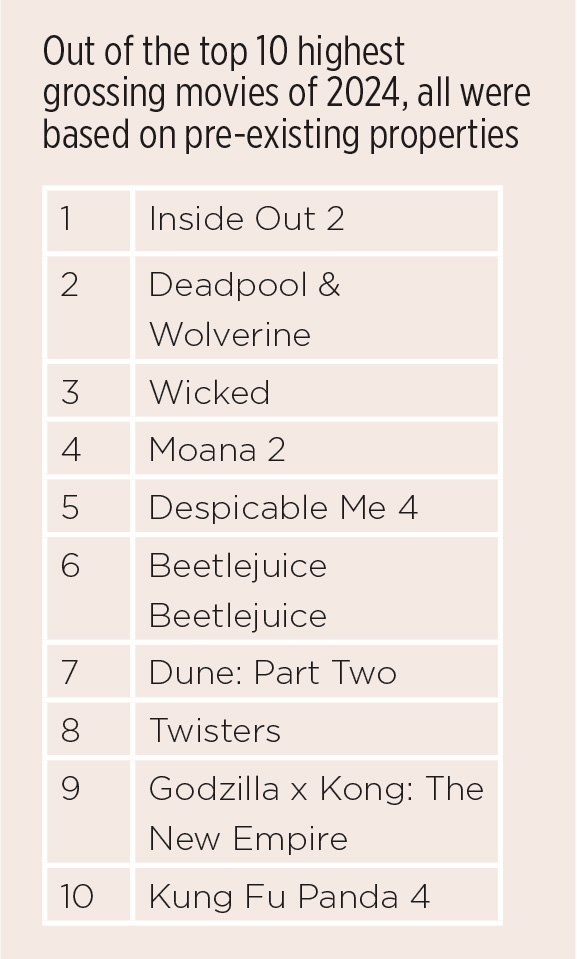

Studio executives wanted more of that, and less experimentation. They wanted to stick to what works—that is, what makes a profit. In 1981, 16 per cent of the most popular movies were sequels, spinoffs or remakes. In 2019, that figure was 80 per cent.

Studio executives are capitalists, at the end of the day. Making a movie is an investment just like any other. And with the average large studio film costing about $100 million from production to promotion and distribution, profit margins are thin. Risk must be minimized, and there’s no safer investment than a story you’ve told before.

Another element was the extreme consolidation of movie studios. Now, five major studios control most of the industry, and small, independent studios often have to go through them for distribution. This means the most profit-minded big capitalist studios control almost everything. Disney now owns the rights to 85 per cent of all movies ever.

This dominance by profit seekers—who are indifferent to artistic quality so long as it makes a buck—explains the extreme aversion to risk and experimentation palpable across television and film. The problem is not just reboots and sequels, but an overall trend toward hollowness, triviality, and design by committee.

In comparison, the Hollywood Renaissance connected with the burning issues of the day and tried to tell the truth. It had the Vietnam war as a major theme, as with Apocalypse Now. Other films tried to chronicle the alienation and malaise of American society, like Taxi Driver. Today, it’s hard to say which, if any films, will be remembered as speaking for us. Most don’t even seem to have anything to say at all. This is the cost of our culture being managed like a stock fund.

Music versus the algorithm

In music, too, the concentration of large amounts of the industry into a few hands has been destructive.

At the top of the industry, a few titans reign. While their spectacles can be interesting and even technically innovative, no one argues that Drake or Taylor Swift have contributed to humanity’s spiritual development.

Meanwhile, for independent artists, the pressure to conform is immense. While advances in technology have made it possible for more people than ever to make and record music without corporate financial backing, artists trying to share their music have never faced greater pressures to conform, to stick to what’s tried and tested.

This is largely thanks to streaming platforms like Spotify. Music streaming runs on razor thin margins. Spotify only turned a profit for the first time this year. This drives them to keep payments to artists low. Spotify pays on average no more than $0.005 per stream. To make 5 bucks, an artist’s song must be listened to 1000 times. This makes it devilishly difficult to support yourself as an independent musician.

Then artists must contend with the playlists. Playlists are all-important to Spotify—much more important than listens outside playlists. They create data points which Spotify can sell to advertisers. For example, if someone plays a “Workout Mix”, they might be advertised gym gear.

Spotify has pushed its users onto playlists, and playlists have become the main way independent music is promoted. This means artists need their songs on playlists to reach an audience. Without that, many languish at fewer than 10 listens.

How do you get your song onto a playlist? You produce something as inoffensive and unoriginal as possible, ideally literally aping what’s already on them. This is necessary to appease the playlist curators—people like “Lofi Girl”, who curates several “lofi chill beats” playlists. These people decide what gets onto the popular playlists, and they want songs that they know their listeners will like—that is, more of the same.

Then there’s Spotify’s algorithm. Again, the pressure is to produce more of the same. To get recommended by the algorithm, it, after all, has to think the listener will like it.

And the algorithm also curates playlists. Getting onto these depends on getting “streams”. To count as a stream, a song must be played for at least thirty seconds. But if it’s played all the way through, it’s more likely to be pushed onto a playlist.

This further restrains creativity. The artist must make sure the song hooks the listener within the first 30 seconds, meaning choruses are appearing earlier in the average song. Songs are also getting shorter, so that the same total amount of listening time per song equals more streams and more money. Finally, artists are incentivized to prioritize catchy singles over cohesive albums, which are useless from the point of view of an algorithm meant to make playlists.

This is a perfect encapsulation of what Spotify drives artists to make: “content”, not art. That’s the catch 22 facing musicians. If they innovate, it’s next to impossible to get an audience. If they don’t, it might feel like selling out, but at least they’ll get paid and get to share their work with the world.

All of this means that while experimentation and innovation exist in music—more than in many other art forms—those new projects tend to remain cloistered in niche corners, unable to break through to the algorithm or playlists.

Spotify is fully conscious of what this is doing to music, and they’re encouraging it. Now they’re pushing the algorithmically-optimized abomination known as “Perfect Fit Content.” Spotify has partnerships with production companies that produce nondistinct, “mood-based” music, often using AI, which is then uploaded under hundreds of different fake artist profiles and inserted into the appropriate mood playlists. Using this “AI slop”, Spotify pushes out real artists and saves on royalty costs.

For a truly human culture

There is a profound human cost to all of this; to the capitalists’ systematic degradation of art. Art is an inherent part of humanity’s centuries-long struggle for meaning, expression and even knowledge. It helps us to raise our sights above the tedium of daily life, to reflect and feel more deeply. It connects us to the experiences of humans from around the world and across time. Art cannot fulfill this function, and even ceases to be art, if it is subject to the ruthless demands of the profit-motive.

This is an incalculably large loss for everyday people who, after another gruelling, mind-numbing day of work, cannot find anything to actually make them feel or think something—or even just to entertain them! Live action Disney remakes and algorithm-optimized playlist content don’t cut it. If anything, they just make you feel more numb and alienated.

The capitalists don’t care about this. To them, our brains and senses are merely potential sources of profit, and all forms of media to them are just different ways to realize that profit. For Spotify CEO Daniel Ek, for example, music is just one of his financial projects, next to the millions he’s invested in an AI military drone startup. These people can’t create anything. All they do is destroy: life and art alike.

Mass culture has never been so firmly under the grip of capital, and the result is a deep stagnation—or decline. Even social media used to be better than it is now. Whereas it used to function as a way for real people to connect with other real people, it’s now dominated by ads and influencers. Everything the capitalists touch turns to rot.

Yet, we could have so much better. With streaming, digital music recording, social media, and so on, we could have free, open access to all the fruits of human creativity. We could democratize art and culture, and humanity could reach creative heights we’ve never seen before. But under capitalism, this will never happen.

Not only because the technological infrastructure is owned by capitalists, but because our lives are. Humanity’s inborn desire to create, learn and connect to others is mangled by capitalism and its cold, inhuman logic. To free ourselves, it’s not enough to boycott this or that tech corporation. We need a new culture, based on a new society that knows nothing of the profit motive or private property. We need a socialist revolution.