Over the past decade, anti-immigration sentiment has grown across the western world. Politicians like Donald Trump, Nigel Farage and Marine Le Pen have gained support by scapegoating immigrants. For many, the reign of Trudeau demonstrated that Canada was bucking the trend. However, in the last few years, Canadian attitudes have changed sharply on immigration.

In a recent poll by Nanos, 71 per cent of respondents said they support reducing the number of immigrants into Canada, versus 26 per cent who were opposed. In a similar poll done by Nanos in 2023, only 51 per cent said they supported reducing immigration—that figure itself being an increase from historic levels of support.

This turn of opinion has generated a feeling of depression for many on the “left.” In their view, the “old Canada” which embraced immigration and multiculturalism is being replaced by one that is mean, nativistic, and racist—the reasons for which they can’t adequately explain.

So what are the real reasons behind changing attitudes on immigration? And how should Marxists engage with those presenting concerns about this question?

Has immigration increased?

In order to answer these questions, we need to start with the facts and figures. First, has immigration really increased by that much in Canada?

In 2015, Canada’s “temporary” population (including categories like temporary workers, international students and asylum seekers) stood at around two per cent of the total population. That figure now stands at over seven per cent, or roughly 3 million people—though Carney has pledged to reduce it to five per cent in the coming years.

The lion’s share of this population (over 80 per cent) is composed of those on work or student visas, two categories which exploded from 2021 on. In turn, the number of temporary workers in the overall workforce has grown from 1.7 per cent of the total ten years ago to 4.5 per cent today.

The number of asylum claimants and refugees is small by comparison, making up roughly one per cent of Canada’s population, or about 500,000 people.

However, that figure has grown steadily over the last 10 years. Sixteen thousand people filed for asylum in Canada in 2015, 64,000 in 2019, 143,000 in 2023, and 170,000 in 2024. Those filing for asylum will usually wait in Canada while their claim is being processed—a process that can often take months or longer.

An ‘open border policy’?

These figures have led some to suggest that Canada had an “open border policy” during Trudeau’s time in office. But that is far from the truth.

Despite the ongoing genocide in Gaza, the Trudeau government initially set a limit of just 1,000 applicants to a temporary resettlement program for Palestinians looking to flee to safety. This figure was later increased to 5,000 after public outrage—a target that was quickly met, resulting in the program’s prompt termination.

Trudeau’s low ceiling for Palestinian resettlement is particularly outrageous given his government’s support for Israel’s actions during his time in office, i.e. the reason Palestinians found a need to flee to begin with.

Sudanese refugees got similar treatment. The civil war gripping Sudan has created the largest displacement crisis in the world today, with an estimated 13 million being forced to flee their homes. Despite this, the Trudeau government set a cap of accepting just 4,000 Sudanese refugees by the end of 2026—a target that has been criticized as too little by Sudanese Canadians hoping to reunite with their loved ones.

However, not all refugees are equal. Canada has resettled some 300,000 Ukrainians and counting via a special program since the start of Russia’s invasion in 2022. In terms of other asylum seekers, one look at Canada’s approval record shows that some nationalities are favored over others.

From 2018 to mid-2024, Iranians formed the single largest bloc of approved refugees in Canada, followed by those from Turkey—each having a roughly 95-per cent approval rate. Those coming from poorer countries tend to face a much lower approval rating. In the same time period, asylum seekers from countries like India, Nigeria and Haiti were approved only around 50 per cent of the time.

This choice of who to accept is not accidental. Russia, Iran and Turkey are all major strategic rivals of Canada, while Israel is not. From the government’s perspective, those fleeing the former countries can be more reliably counted on to support its policies abroad. In deciding who gets refugee status, geopolitics and not human rights considerations play the greater part.

Why has immigration increased?

The idea that Canada had an “open border” over the last 10 years is not based in fact. That said, Canada has experienced a large uptick in immigration—particularly from those on work and student visas. But why has this happened?

In a previous article, we explained how the main push for this kind of immigration came from employers and colleges looking to push down wages and pad their revenues. However, it is worth adding that this process did not begin with Trudeau—though he massively accelerated it.

The first iteration of what later became the temporary foreign worker (TFW) program was introduced to Canada in 1966. Back then, its use was limited to employers in agriculture. In 2002, the program was expanded under Jean Chretien to a number of other low-wage occupations for the first time. The election of Stephen Harper, a Conservative, in 2006 brought forth an even further loosening of the TFW program—so much so that he was forced to back off on certain measures after a public outcry.

The main purpose behind the TFW program was (and is) to give Canadian business access to large pools of cheap labour with limited rights—the result being a lower wage bill and increased profits. The program was repeatedly expanded from the 2000’s on as the Canadian economy started to lose steam and the pressure to retain profit margins grew.

Importantly, this period also coincided with a dramatic fall in Canada’s productivity. In part this was because businesses’ dependence on cheap labour disincentivized them from boosting their profits in other ways, namely through the investment in new technologies and machinery.

Both Liberal and Conservative administrations helped facilitate this process—in reality, a scheme to suppress wages—in response to demands from the bosses.

Who created the refugee crisis?

The Canadian government and its corporate patrons have also created thousands of asylum seekers as a result of their quest for profits at home and abroad. .

In 2025 thus far, the top three nationalities seeking asylum in Canada were Indians, Mexicans and Haitians. In all three cases, the actions of the Canadian government played a direct role in creating the present flow of refugees.

Indian immigrants formed the largest bloc of those holding work and student visas in Canada in recent years. The Canadian government enticed this kind of immigration by loosening restrictions on work hours for international students—again, to the benefit of employers seeking cheap labor and colleges looking for revenues—and by offering most graduates a work permit once they completed their studies. Those who immigrated planned their lives accordingly, having been promised that they could remain in Canada.

However, after backlash against high levels of temporary immigration, the Canadian government suddenly reversed its earlier promises—leaving hundreds of thousands of Indians and others in limbo. Having no other option, some applied for asylum so as to remain in Canada—though it only represented a minority of those here. Many of those applications are now being rejected, with deportations set to follow.

The Canadian government has also played a role in the destabilization of Mexico and Haiti, helping to drive millions from those countries and into places like Canada.

The signing of NAFTA in 1992—a deal which mostly benefitted U.S. and Canadian corporations—resulted in the destruction of Mexico’s agricultural sector, putting millions of small farmers out of work over the following decades. This, combined with the general breakdown of Mexican society post-NAFTA, led to a dramatic and sustained increase in the number of Mexicans fleeing north, seeing no other opportunities for work outside of the U.S. and Canada.

In Haiti, Canada played a supporting role in overthrowing the country’s first elected government. Re-elected in 2000, the left-wing presidency of Jean Bertrand Aristide came to be seen as a threat to U.S. and Canadian corporate interests. In 2004, a U.S operation, in which Canada participated, ousted him from office. Since then, Haiti has descended into chaos and barbarism—a consequence in part of the 2004 coup and the destabilization it helped foment.

Canada’s politicians have become experts in blaming refugees for many of the country’s problems. However, they ignore how it was policies they supported that helped fuel the flow of refugees—including policies which continue to this day.

Is immigration depressing wages?

While the “left” tends to explain the falling support for immigration in Canada by a rise in racist sentiments, the reality is not so simple. Polls show that the most common reasons for supporting reduced immigration mainly come from economic, not cultural concerns.

In a recent report by the Environics Institute, it was revealed that only 13 per cent of Canadians who are wary of immigration felt that way because it represented a “threat to Canadian/Quebec culture”. Instead, most cited issues like the lack of jobs, the pressure on housing prices, and the cost to public finances as their reason.

These worries stem from real problems working class people face as the crisis of the system gets worse. Therefore, it would be a serious error to simply dismiss these concerns as a result of prejudice. To do so would only alienate people and answer nothing. These are understandable concerns which must be considered and answered.

First, are temporary immigrant workers used to push down wages? Yes, they are.

Business lobbies like the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB) have objected to this by claiming that there are “zero” cases of temporary workers being paid less than comparable Canadian workers. However, that is not the problem. The issue is not one retail worker being paid less than another for performing the same job. Rather, the more desperate position of migrant workers under Canada’s current immigration setup creates a large pool of cheap labour. This weakens the negotiating power of other workers, allowing employers to more easily find workers without needing to raise wages.

Moreover, many workers hired through the TFW program are legally tied to a single employer. This, combined with the constant threat of deportation, gives even greater bargaining power to the boss, who then doesn’t need to worry about low wages or poor conditions leading to turnover at his business.

The effect of this can be seen in the data. In a recent report, the Bank of Canada revealed that the average non-permanent migrant worker is now paid 22.6 per cent less than a worker born in Canada. In 2014, they were paid 9.5 per cent less.

This is not a problem with immigration as such, but an immigration system designed to restrict the rights of certain workers and to serve the bosses. More generally, it is a failure of capitalism to provide gainful employment to everyone, though the resources exist to do so.

Is immigration to blame for the housing crisis?

The same applies to housing. In a tight housing market, it follows that a dramatic increase in population will have the effect of raising rents and housing prices at least to some degree. This did appear to happen in certain areas after immigration rose in 2021 on, such as in student housing complexes.

However, rents and housing prices in Canada were increasing long before the jump in immigration took place, meaning its effect was only secondary. The primary cause of the housing crisis was not immigration, but the combined failure of the government, developers and construction firms to build homes in the years before.

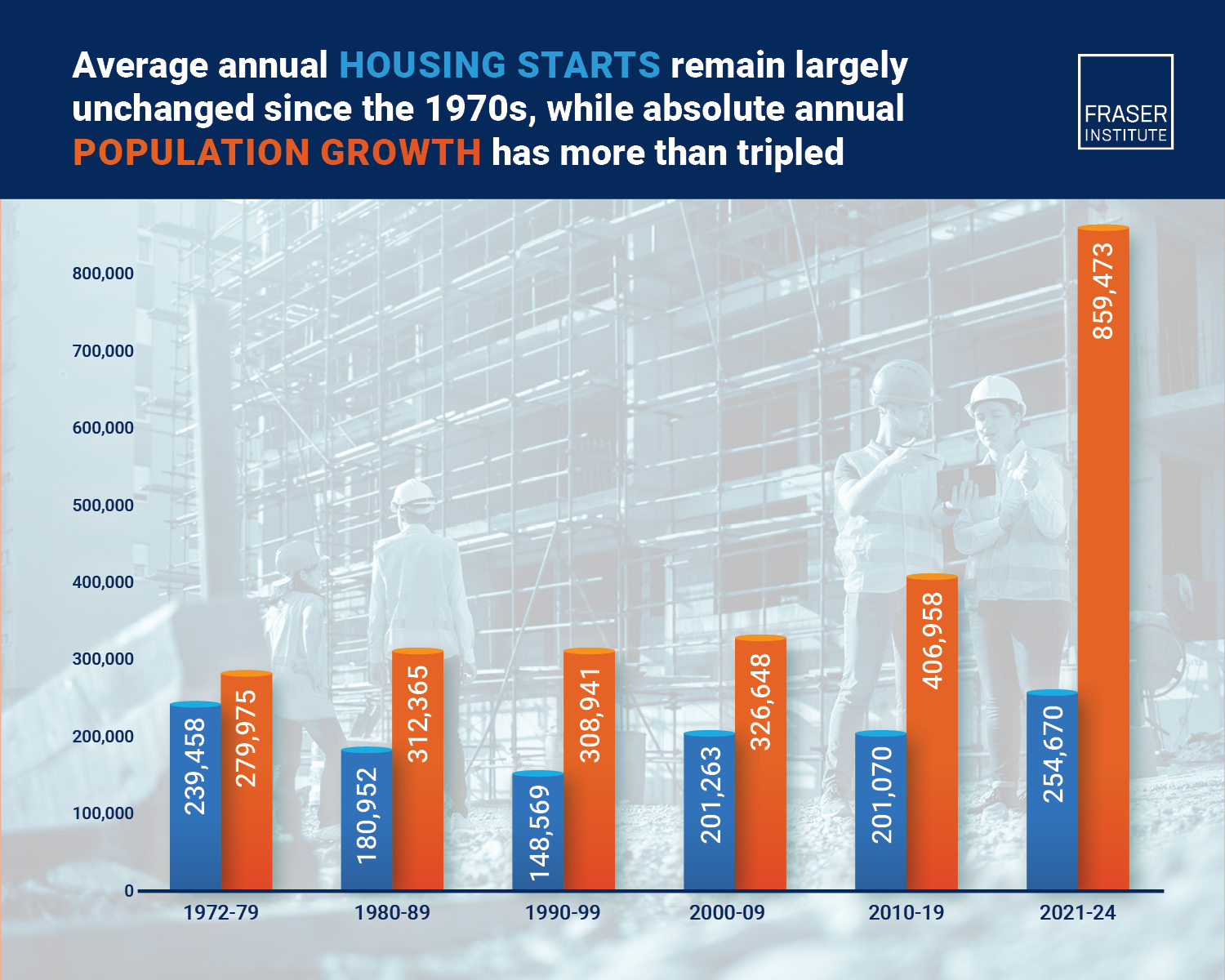

This is borne out in the data. In a recent report, the Fraser Institute looked at the relationship between population growth and housing starts in Canada from 1972 to 2024. It found that while population growth increased steadily during that time, the number of annual average housing starts actually fell below the absolute level achieved in 1972-76, only reaching it again after 2022.

Let’s compare time periods to illustrate. In the period from 1972 to 1976, the Canadian population grew by roughly 300,000 people per year, while housing starts grew by close to 250,000. From 1997 to 2001, the population only grew by roughly 284,000 per year, less than in the earlier period. However, housing starts fell dramatically to just 150,000 a year. This ratio remained more or less consistent until 2022.

Importantly, the 1997-2001 period was also when the federal government stopped building public housing, a factor which likely contributed to the dearth of new homes back then—and which continues to fuel the housing crisis today.

We could also go further back to demonstrate our point. In the immediate post-WWII period, immigration levels were actually higher than they are today. However, most people then could generally count on finding a job at a good wage, a pension after retirement, and even purchasing a home. This despite the fact that immigrants back then were generally less educated than they are today.

What changed? The problem today is not the volume or quality of immigration, but the failure of Canada’s capitalists and different levels of government to build affordable homes at the levels they did in the past. The crisis bedevilling Canada is not a crisis of immigration, but a crisis of capitalism.

What about refugees?

That brings us to refugees. Don’t large numbers of asylum seekers place an undue burden on the system? Let’s consider the facts.

First, due to Canada’s private sponsorship program for refugees, many of those resettling in Canada receive little government support at all. In these cases, the “private sponsor,” (which can be an individual, group, or organization) picks up the tab for the first year. In 2024, Canada resettled roughly 50,000 refugees—around 30,000 of these were privately sponsored.

Second, many if not most asylum claimants do work and support themselves like other Canadian workers. The reason that some don’t is at least partly due to the fact that the government doesn’t allow them to work immediately.

It is estimated the average asylum claimant waits 45 days to receive a work permit in Canada, though many people report waits as long as two or three months. This has even led to figures like Doug Ford blaming Ottawa for why so many asylum seekers are out of work, saying that for the latter it’s “not their fault.”

But what’s the cost of those who do receive government support? Many readers have probably seen a viral post claiming that asylum seekers in Canada receive significantly more than the average Canadian pensioner. If true, we could certainly understand why people would see this as unfair. However, this claim, like many others, is greatly exaggerated.

What are the facts? In Canada, government support for refugees and asylum seekers is generally tied to the social assistance rates that other Canadians receive. In Ontario, this amounts to a maximum of $733 a month for an individual. To compare, working a minimum wage job in Ontario at 40 hours a week would net around $3,000—or more than four times what a refugee would likely get.

In addition, refugees or asylum seekers can receive a one-time start-up fund of around $3,000 for an individual—money which is often used to settle travel debts. Due to the affordable housing shortage, some asylum seekers have been posted at hotels at the government’s expense while they search for a place to live. However, these numbers have been declining and the federal government recently announced that it would be suspending the program.

It is difficult to estimate the total amount spent on supporting refugees and asylum seekers due to poor data collection. However, rough estimates using publicly available data suggest a total ranging anywhere from $2-5 billion a year. This would roughly align with what other countries spend on their refugee programs.

Two to five billion dollars is not chump change. It is completely understandable for some to be upset at people being posted at hotels while they struggle to make rent themselves. However, things must be put into perspective.

In the last few years, the federal and provincial governments have doled out over $50 billion in subsidies and other goodies to auto and battery manufacturers. This despite the fact that many of them have already backpedaled on their promises to use the money to expand production and create jobs. It is estimated that Canada loses $15 billion a year due to corporations hiding their money in offshore tax havens. These are just a few examples.

The real “welfare bums” blighting society are Canada’s corporations—not refugees and asylum claimants. Further, these freeloaders and their political enablers have every interest in scapegoating refugees to deflect blame from themselves.

Why do people blame immigrants?

But if the above is true, why do people still blame immigration for the country’s problems? And why now?

For starters, the change in attitude towards immigration is not unique to Canada. In almost every advanced capitalist country, public opinion has shifted in recent years against immigration, while political parties that oppose immigration have gained support. Canada is now being ensconced in this process, although it takes on its own unique features.

It should be added that in Quebec this process takes on still more unique features, owing to the presence of the national question and the debates over use of the French language. This side of the question will be explored in other articles.

How did this happen? In the past few decades, and particularly since 2008, wages of Canadian workers have either not grown by much or stagnated. Unemployment has hit over seven per cent, with the figure for youth pushing closer to 15 per cent. The cost of rent or of purchasing a home has exploded.

In turn, the number of people believing that the country is moving in the right direction has reached record lows. Trust in institutions like the parliament and the banks have collapsed. The same can be observed in almost all countries.

People are angry. However, this anger is not entirely directed at immigration. In its 2025 report, the Edelman Trust Barometer revealed that 61 per cent of Canadians believe that “the wealthy’s selfishness causes many of our problems.” Seventy-three per cent agreed that “the wealthy don’t pay their fair share of taxes.” This gives us an idea of the real mood.

In this environment, a major party that presented fighting, class solutions would have earned significant support and helped redirect the anger pointed at immigration. But no such party existed. The NDP could have played this role. However, they chose instead to enter an alliance with the hated Trudeau government, while adopting a program that was indistinguishable from the Liberals. The NDP was therefore not seen as a serious option for change.

The anger had to go somewhere. The NDP being absent, the Conservatives and media outlets started shifting the blame to the immigration system. The Liberals soon followed. Of course, left out was the fact that both parties had designed that same system in the decades before to service their friends in big business. But no matter—someone needed to be blamed.

Why is Poilievre popular?

The growth in support for Poilievre is a particular mystery to many on the “left.” In fact, it is no mystery at all. During the election campaign, Poilievre not only railed against an “out of control” immigration system (which, in any case, is what the Liberals did too)—he also railed against the rich and powerful (“boots not suits”) and wealth disparities in Canada (“the have-nots and the have-yachts”). This found an echo with millions, including a significant portion of the youth.

Of course, Poilievre and the Conservatives are no friends of the Canadian worker—that should go without saying. Politicians will say whatever they need to say to get elected. However, there is no question that, in a distorted way, Poilievre has managed to capture the anger of a large layer of workers and young people in Canada. This should not be too hard to understand.

It should also be considered how Poilievre criticizes immigration, in order to better understand why his ideas are resonating with so many, including many immigrants.

The blanket comparisons of Poilievre to the likes of Donald Trump and Nigel Farage are not useful, and would fail to convince anyone with illusions in him or who has a basic understanding of the facts. True, there are certain similarities between these figures. But there are also important differences.

Let’s consider one example. Poilievre has recently called for the end of the TFW program for all positions outside of agriculture. This would effectively mean returning the program to its original 1966 form.

How does he justify his stance? He does so by arguing that the TFW program has been used by employers to push down wages, and this must be brought to an end. Is he wrong or right in saying that? He is right.

In defending his position, he went on to say about migrant workers:

“They just want to have a better life, and in many cases, they are the victims of a system that abuses and rips them off at the same time as destabilizing our housing, job market and social services.”

Whether or not Poilievre is being sincere is besides the point. We have reason to doubt his intentions like we do with every capitalist politician. His statement is only important for one reason: it reveals what he thinks he needs to say to get support from the working class given their present mood.

And what is that mood? Simply, that workers are concerned about the economic impacts of immigration, but they are not ready to entertain racist tropes or blame immigrants themselves for those problems.

Compare this with Carney’s position. The Carney government has already carried out significant attacks on migrants, much to the disappointment of those on the “left” who promoted him as the “lesser evil.” However, he has stubbornly defended the TFW program against Poilievre’s criticism.

Why? Not for any humanitarian reason. In a recent speech, Carney challenged Poilievre by saying that access to temporary foreign workers was the top issue after tariffs for businesses he spoke to around the country—and so it should not be touched. Carney was joined in his defence of the program by the CFIB, a major business lobby, who outrageously claimed that Poilievre’s claims about cheap labour were simply a lie.

So there we have it. Is it any wonder then that some workers see immigration as a scheme hatched by elites to destroy their living conditions? Is it any surprise that people would call for less immigration when this is how it’s defended?

The fact that Poilievre continues to enjoy large support in the polls should be of no surprise to anyone—though it continues to be a surprise to some.

Is Canada becoming more racist?

The bulk of the “left” has been completely disoriented by the public’s sharp turn against immigration. The enduring popularity of Poilievre has proven particularly confusing, which some speak of in terms of how others describe the rise of Hitler and Mussolini. Of course, what’s really confusing is not how the average worker thinks, but how much of the “left” thinks—if in fact they think at all.

In their eyes, Canada has succumbed to a terrible and sudden virus of racism, the origins of which are never adequately explained. Of course, the fact that prejudiced ideas have been adopted by a certain layer of the population cannot be denied—although the deeper reasons behind these attitudes also need to be examined. However, explaining the fall in support for immigration in general by a rise in prejudice presents some serious problems.

First, in Canada, the majority of people actually supported high levels of immigration until the last few years. In 2018, a Pew poll found that 68 per cent of Canadians felt that immigrants “make our country stronger.” Only 27 per cent felt that immigrants “are a burden.” Have people suddenly become more racist since then?

Second, if the problem is solely racism, how is it that so many immigrants themselves support reduced immigration? In the aforementioned Environics poll, immigrants of every generation registered almost identical levels of opposition to immigration as those born in Canada. Those identifying as “racialized” were actually slightly more opposed to immigration than those identifying as “white.”

This can also be seen in terms of electoral support. In a Nanos Poll from April, it was shown that 42.7 per cent of new immigrants planned to vote Conservative, a few points higher than where the general population stood at the time—and this despite Poilievre’s tough talk on immigration. In the election itself, the Conservatives placed first among immigrants in areas such as Toronto’s 905 region.

Third, while polling shows that most Canadians support reduced immigration, their views on immigrants themselves are far more complex. In a recent Angus Reid survey, 58 per cent of Canadians agreed with the statement that “temporary foreign workers are being blamed for economic problems they don’t cause”—including 39 per cent of Conservative voters.

In a 2023 Nanos survey, 69 per cent of Canadians said they supported having temporary foreign workers becoming permanent residents or citizens, while 59 per cent supported allowing migrant workers to change employers. In the Environics poll, huge majorities agreed that youth “are fortunate to grow up surrounded by friends of all different races and religions” (88 per cent support) and that “multiculturalism has contributed positively to the Canadian identity” (78 per cent support).

These are not the attitudes of people steeped in racist hatred—quite the opposite.

The failure of the left

One of the reasons for this change in sentiments is the failure of the “left” to provide a clear explanation for the crisis and its effect on working class people. Quite often, the left are united, hand in hand with the liberal establishment. This was seen with the NDP propping up the Trudeau government for over two years, or Bernie Sanders campaigning for Joe Biden.

This dynamic has meant that, as workers search for an alternative, the only people who appear to be offering an explanation are rightwing demagogues who blame immigration for the economic woes we all feel.

In response, many on the left have defended immigration in purely moral terms, as if opposition to it was simply a case of people being “hateful”. The real economic anxieties of workers are frequently sidelined, while lectures on the moral virtues of supporting immigrants are given prime focus. This approach convinces nobody and helps nobody—least of all immigrants.

The results of this approach can be seen clearly in Britain where the anti-racist movement has been led by Stand Up To Racism, a front affiliated with the Socialist Workers Party, for the past number of decades. Their approach has been to moralize: racism and Islamophobia are bad; refugees are welcome; and migrants are good people.

This approach does nothing to address the real concerns working-class people have about the lack of housing, jobs, and services. The result has been that Tommy Robinson, a well known far-right activist in the U.K., managed to rally over 100,000 people on the streets of London against immigration through the use of demagogic anti-establishment rhetoric.

While things are nowhere near this situation in Canada, the left here uses similar arguments.

To cite one example, a recent protest in Toronto against anti-immigrant demonstrators was held under the banner of “No to hate, Yes to immigrants.” How does this slogan help to convince someone who has concerns about the economic impacts of immigration? What reason is there to support immigrants, other than to be told that doing otherwise would be “hateful”? The content of the slogan is completely empty. In truth, it would sooner be adopted by a large business owner or a priest than it would the average worker. But if the point isn’t to convince the average person, then what is the point—other than righteous posturing?

If the left continues to pursue this same approach, it will only serve to strengthen the anti-immigrant movement and provide them with a wider foothold among a layer of disaffected workers looking for an answer.

To make matters worse, certain activists defend immigration using the arguments of the capitalists themselves. The most notable of these is the suggestion that “migrants do the jobs that Canadians don’t want to do.”

But haven’t we heard this before? In fact, this is exactly what big business claimed during the alleged “labour shortage” that followed the pandemic. They did so to help bolster their argument for more temporary immigration in order to “fill the gap.”

However, the issue then was not a labour shortage, but a natural reluctance by some to accept or stay in jobs offering poor conditions and minimal pay—especially if they knew a better offer might be just around the corner. In other words, the problem was not one of too few people willing to work, but of too few employers willing to offer suitable working conditions and pay.

The same holds true today. The capitalists defend high levels of temporary immigration because migrants can be more easily compelled to work under bad conditions due to their tenuous position and limited rights—not because “Canadians don’t want to do them” as such.

In repeating this argument, the “left” unwittingly provides cover for the bad dealings of the employers and undersells the expectations of migrant workers on the job. Moreover, they shift the blame for unemployment to Canadian-born workers themselves—who we can only assume are too pampered to accept a job that leaves them and their families in poverty.

Is it really so hard to understand why these people are seen as out of touch?

The Marxist approach

The Marxist approach differs markedly from this.

Marxists do not defend immigrants on the basis of abstract moral principles. We defend immigrants on the basis of fostering the greatest possible unity of the working class—immigrant and non-immigrant, documented and undocumented. We oppose measures that restrict immigrant rights because it puts all workers at a disadvantage against the boss. The strength of our class is our foremost concern.

The problems facing Canadian workers are a problem of capitalism in decline—not the number of foreigners. However, what might be perfectly clear to us is not clear to everyone. The complete failure of the NDP and the wider “left” to offer solutions to the problems facing society has made it possible for anti-immigrant ideas to take hold, as it has in many countries. The blame is entirely theirs—not the working class’.

However, we do not lament this situation or fall into depression. Beneath the concerns around immigration are real economic anxieties and a deep class anger looking for an expression, however confused it might be. The task of Marxists is to actually listen to people, connect with their anger, separate the positive from the negative, provide concrete answers, and gradually help direct workers and young people against the actual source of their woes—capitalism.

How can this be achieved?

The first point we should make is that the real culprits behind Canada’s problems are not refugees living in hotels, but the billionaires living in mansions. The real criminals are not migrants looking for work, but large corporations who treat the government like an ATM and the politicians who allow it to happen. The only problematic minority in Canada are the rich.

Furthermore, the Canadian government that deprives migrants of their rights is the same that strips trade unions of their rights the minute they hit the picket line. The bosses that exploit migrant labour are the same that carry out mass layoffs affecting Canadian-born workers. We have a common enemy in the ruling class.

In terms of the TFW program, we start by agreeing that the program has been used for decades to undercut wages. However, the solution is not as simple as cutting off the taps.

If the TFW program ended, employers would still have an incentive to minimize their wage bill. This could be achieved by reducing services, increasing the workload for existing employees, or even hiring people under the table at their preferred rate. In some cases, the business may be so dependent on cheap foreign labour that it shuts down altogether. In short, we do not trust the bosses to do right by their workers.

Instead, we demand that migrant workers be given the same rights as other workers—particularly the right to change employers. This makes it harder to keep wages low and helps put upward pressure on the wages of all workers. Moreover, we believe that unions should expend greater efforts on organizing low-paid, migrant workers. This would further help prevent the boss from undercutting workers, as well as cement greater unity of the working class overall.

Of course, these measures alone could only achieve so much. Many large employers like Tim Hortons, Maple Leaf Foods and Loblaw have built their business models around cheap foreign labour, and would resist measures to improve the position of migrant workers tooth and nail. Therefore, we demand that any large company that puts up resistance should be punitively nationalized without compensation in the interests of workers at large.

In terms of housing, we explain that private developers and governments—not temporary workers and students—are chiefly to blame. The solution is not to stop immigration, but to nationalize the large developers and construction firms to initiate a public housing spree that provides a decent place to live for all.

In terms of refugees, we illustrate how foreign meddling by the Canadian government helps fuel the refugee crisis in the first place. No one really wants to leave their home, after all. The only way to end this situation is to end Canadian and U.S. imperialism which is its source.

However, for those who do choose to come to Canada, we believe in providing them with work, language courses, job training, and other resources which would allow them to play a useful and fulfilling role in society. The wait for work permits should be abolished. The hotels which house refugees and charge monumental sums to the government should be expropriated and turned into temporary housing for all of Canada’s homeless population.

Capitalism breeds ghettoization and poverty for many asylum seekers. We are for the integration of newcomers into the wider working class and the breaking down of barriers that exist between them. This would be to the benefit of all working people.

However, this does not exhaust the question at hand.

In the final analysis, the source of Canada’s problems is the crisis of capitalism. The anarchy in the labour market, the inability to build housing, the neglect of public services, the closure of factories and shops, the rampant theft of taxpayer money by big business, the corporate control of Ottawa—all of these find their origin in the senile decay of the so-called “free market.”

Therefore, our final aim is to ditch this inefficient system and replace it with a planned economy under democratic workers’ control. Capitalism doesn’t just waste resources, it wastes people.

Freed of these limits, we can put every individual to productive use and allow each of them to reach their highest potential. This would usher in a totally new society in which everyone could be guaranteed a secure and fulfilling life—wherever they might come from.