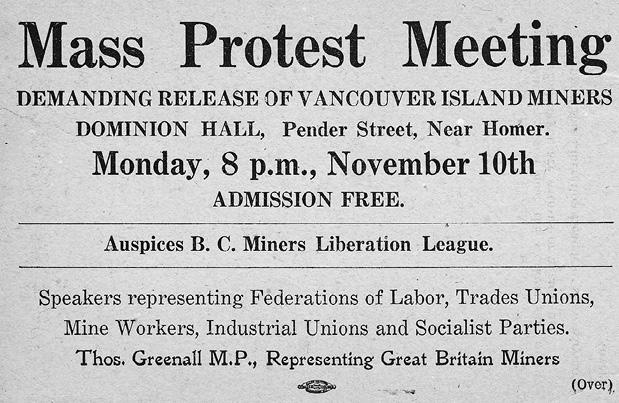

In August 1913, Vancouver Island was engulfed in class struggle. The coal miners strike of 1912-1914, the Great Strike as it is called, crippled Vancouver Island for nearly two years as workers flew the red flag on Canadian soil. Coal miners on Vancouver Island rose up against the mining bosses and defied the power of the Canadian state, taking over the town of Ladysmith for three days, and bringing the Island to the brink of an all-out class war.

The strike ended in a crushing defeat for the workers, but it was an important school for the young Canadian working class. The Island miners’ strike paved the way for industrial unionism in Canada and produced a new layer of militants who would go on to lay the foundations of the Communist Party of Canada in the following years.

Although the Great Strike is one of the most significant battles in the history of the class struggle in Canada, very little is known about it. It is our task to defy the ruling class’s deliberate attempts to suppress our history and bring the heroic miners’ strike to light in order to strengthen and inspire the workers’ movement. As the crisis of capitalism deepens, new class battles are erupting and new class fighters are being educated in struggle. It is therefore crucial that we study the Great Strike, to understand its lessons and to explain its defeat, in preparing ourselves for the battles of the future.

Development of capitalism

The Great Strike erupted as part of a wave of class struggle that was a reflection of the development of Canadian capitalism. As capitalism developed in the early 20th century, farmers from the countryside and immigrants from Europe and Asia were hurled into the growing industrial boomtowns across Canada and Quebec, which led to the growth of the working class.

There was an explosive development of the resource industries, and a rapid rise in manufacturing and the construction of canals and railways. The coal mining industry rapidly expanded after Confederation, up until just after World War II. The industry spread westward with major commercial centres emerging on Vancouver Island in the early 1850s. The coal industry provided the most important energy source to heat homes in the growing cities across Canada and Quebec, and to fuel expanding rail and steamship networks, industrial machinery, and firelight, prior to the use of electricity.

With the development of capitalism came vicious exploitation. The working conditions in Canada and Quebec were atrocious. Workers struggled to feed, clothe and shelter themselves. Immigrants, especially Chinese workers, were hyper-exploited and this discrimination was used to drive down wages. Workers looked for a way out of their misery and started forming trade unions.

The ruling class ruthlessly fought all attempts of organization with the use of blacklists, spies, intimidation tactics, and scab labour. The bosses refused to recognize or negotiate with any trade union. Strikes were illegal and when bosses could not break them government troops and militias were called in to crush strikes and force workers back to work. Trade union activists, socialists, and communists were regularly arrested and deported by the government.

But this repression led to a rise in class consciousness, radicalizing many layers of the working class, leading to explosive class battles from the late 1800s on. The pre-World War I period in Canada was one of heightened class struggle, as it was in many other countries. Strikes erupted across the country as industrial unions were trying to gain a foothold. The decade was one of industrial strife with at least 1,319 strikes taking place between 1901 to 1912.

Workers were increasingly turning away from the earlier conservative craft unions and towards the international industrial unions based in the United States. Craft unionism is a model of trade unionism in which workers are organized on the basis of their particular craft or occupation. As an example, in the construction and building trades, all carpenters would belong to the carpenters’ union, the painters would belong to the painters’ union, electricians would belong to the electricians’ union, etc. This meant that workers in different crafts or trades working at the same factory or job site would be divided into different unions.

Each craft union had its own administration, its own policies, its own collective bargaining agreements, its own union halls, etc. The craft unions generally organized the more skilled workers while leaving the unskilled or semi-skilled workers at the mercy of the bosses without a union. The craft union leaders were concerned that unskilled labour would dilute their power and position at the workplace given the scarcity of highly skilled labour.

This division of the working class by craft and skill created a narrow, selfish outlook of the craft union leaders, who were mainly interested in protecting their own skilled workers. In general, they tended to favour arbitration and consensus with the bosses as opposed to strike action and class struggle. This of course does not mean that the craft unions never engaged in bitter strikes, but over time the craft unions did become increasingly conservative and highly bureaucratized. This made strike and solidarity action difficult to achieve. The total shutting down of a factory or job site could become difficult in a situation where only some of the workers were on strike and others were not according to which craft union they belonged to.

Craft unionism became the dominant trend in the early years of the trade union movement. But as the productive forces under capitalism continued to develop and grow, so too did the division of labour. The jobs of the skilled craft workers were increasingly disappearing through the subdivision of tasks among less-skilled workers and with the increasingly rapid introduction of new machinery. This development of the productive forces and the division of labour led to the introduction of the assembly line, mass production, and Taylorism or “scientific” management.

The workers increasingly came to view the craft unions as old relics of the past, incapable of serving the needs of the working class in the face of developing industrialization and mass production. Factories and work sites grew larger and larger as mass production techniques were introduced everywhere across nearly all industries. The working class as a whole faced larger and larger corporations in control of ever-growing processes of mass production where a complex division of labour meant the use of more unskilled and semi-skilled workers. The craft union leaders in the United States for example had failed to organize workers in the steel industry for decades by insisting on dividing the workers at massive steel factories into different unions according to trade.

Faced with the assembly line and Taylorism, the working class needed new forms of organization in the class struggle. This led to industrial unionism, whereby the goal is to organize all workers in the same industry into the same union, regardless of differences in skill or craft. It was only through the methods of industrial unionism that the steel industry, for example, was eventually unionized in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

For decades, there had been a titanic struggle between the old craft union leaders and the newer industrial unions. This was exemplified in the struggle of the Congress of Industrial Organizations for industrial unionism against the old craft unionism of the American Federation of Labour (AFL). The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), the union that represented the miners during the Great Vancouver Island Coal Strike of 1912, was organized on an industrial and not a craft basis. The UMWA was one of the charter members of the Congress of Industrial Organizations when it was formed in 1935.

In the early 20th Century, the ground for industrial unionism was fertile in Canada too, particularly in the West. The trade unions in Eastern Canada were dominated by craft unionism and tended to enforce the status quo. But in Western Canada, things were different. With the development of the productive forces, the mining and logging industries in Western Canada for example, involved massive worksites and made more use of unskilled labour. The previously slow pace of population growth and industrial development in the West meant that the workers there were not very familiar with the old, conservative traditions of the craft unions in Eastern Canada. Nor were they dominated by these conservative traditions, and so many workers in Western Canada came to embrace not only industrial unionism but also militant, radical methods of class struggle shunned by the established trade union bureaucracy out East.

It should be pointed out, however, that even at this time the industrial unions had developed their own powerful bureaucracies with their own interests and conservative traditions, as the workers on Vancouver Island would come to discover. The period from the 1890s to 1914 was a period of intense economic upswing. In the decades of upswing before the war, the leadership of the labour movement internationally began to accommodate itself to capitalism. This trend was also present in the industrial unions expanding across North America.

Political ferment among the workers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries reflected itself in the rise of socialist parties. In 1901 the first socialist party was founded, the Socialist Party of British Columbia (SPBC). And as socialist ideas spread across the country, the party developed into a national party, the Socialist Party of Canada (SPC), in 1904. While the SPC dominated on the West Coast, the Social Democratic Party of Canada (SDPC), a split off from the SPC, founded in 1911, was dominant in the East . Both parties were small, each had about 3,000 members. The parties had not established a program or methods, but they were the embryo of the future Communist Party of Canada. While the SDPC was formally Marxist, in reality it was a heterogeneous party with a range of tendencies, from revolutionary Marxists to right-wing reformists. The SPC took an ultra-left turn and refused to do systematic work in the trade unions, cutting themselves off from the class struggle. And yet somewhat contradictorily, the party considered the class struggle to be limited to parliamentary elections.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ian Angus describes the early days of the SPC in Canadian Bolsheviks: The Early Years of the Communist Party of Canada:

“The Socialist Party of Canada prided itself on its doctrinal purity. It would have no truck or trade with reformers or reforms: it was for revolution, and nothing less. The SPC even refused to join the Second International, on the grounds that the British Labour Party was a member. In the language of the time, the SPC was an “impossibilist” party: the word was coined as a contrast to the “possibilist” socialists who favored trying to win whatever reforms were possible within the framework of capitalist society. In the SPC’s view, reforms were at best a waste of time, at worst a diversion from the struggle for socialism. It should be noted, however, that the party deviated from this policy in practice: the socialists elected to provincial legislatures (three in British Columbia, one in Alberta) fought for and won a number of important reforms, most notably improved working conditions in the mines.

“Until 1912 the Socialist Party had held itself aloof from the trade union movement. Although a majority of its members were unionists, and although some union locals expressed support for the Socialists, the party’s principal spokesmen were openly critical of, even hostile to, the organized labor movement. The party’s best-known theoretician, E.T. Kingsley, argued that the conflicts between employers and workers were not part of the class struggle at all–they were mere “commodity struggles”, disputes over the division of wealth in capitalist society, and hence of no interest to socialists. The class struggle, according to Kingsley and the SPC leadership, existed only on the political level: in practice this meant that the class struggle was limited to election campaigns. For all its “impossibilism,” the SPC was expounding a view not far removed from reformism.”

The election of SPBC members, James Hawthornthwaite of Nanaimo and Parker Williams of Ladysmith to the legislature soon after the party was founded in 1901 gave way to the passing of a number of reforms such as an eight-hour underground work day for miners, protection of unions from lawsuits for damages, amendments to the Coal Mines Regulation Act, and the first Worker’s Compensation Act.

But as soon as these pieces of legislation were passed, their implementation came into conflict with the capitalist system. It became clear to workers as to how far any piece of legislation was going to protect them from the exploitation of the bosses. For example, the Coal Mines Regulation Act guaranteed miners a minimum of $3.30 per day and yet miners were being paid much less. The Act also set out safety regulations which were all ignored. The Act also stated it was illegal for mining companies to interfere with the work of Gas Committees and yet bosses routinely dismissed workers for reporting gas in the mines. While the legislation for an 8-hour shift underground had been passed, the miners worked from dawn to dusk, including in the pits. The legislation on workers’ compensation was meaningless and would only actually come into force in 1917. Until then, when miners were injured they would receive no form of workers’ compensation. These pieces of legislation only served to expose the hypocrisy of bourgeois law which fundamentally exists to serve the interests of the ruling class.

By the late 19th century British Columbia’s economy was booming with industries in forestry, fisheries and mining. By 1900, Vancouver Island was providing 50 percent of Canada’s coal exports. The Island mines were also the main exporter of coal to the state of California. The economy of the mid-Island region was almost completely dependent on the coal industry. Up until 1923, over 90 percent of the mid-Island region either worked for the mining companies or in the sectors that relied on the coal industry. In other words, the workers of the mid-Island region were at the mercy of the mining bosses and the vicious downturns of capitalism. In the years preceding the Great Strike the market for coal was declining as oil made further inroads in the fuel market, further compounding the precarity the miners faced in the uncertain market.

Living and working condition in the mines

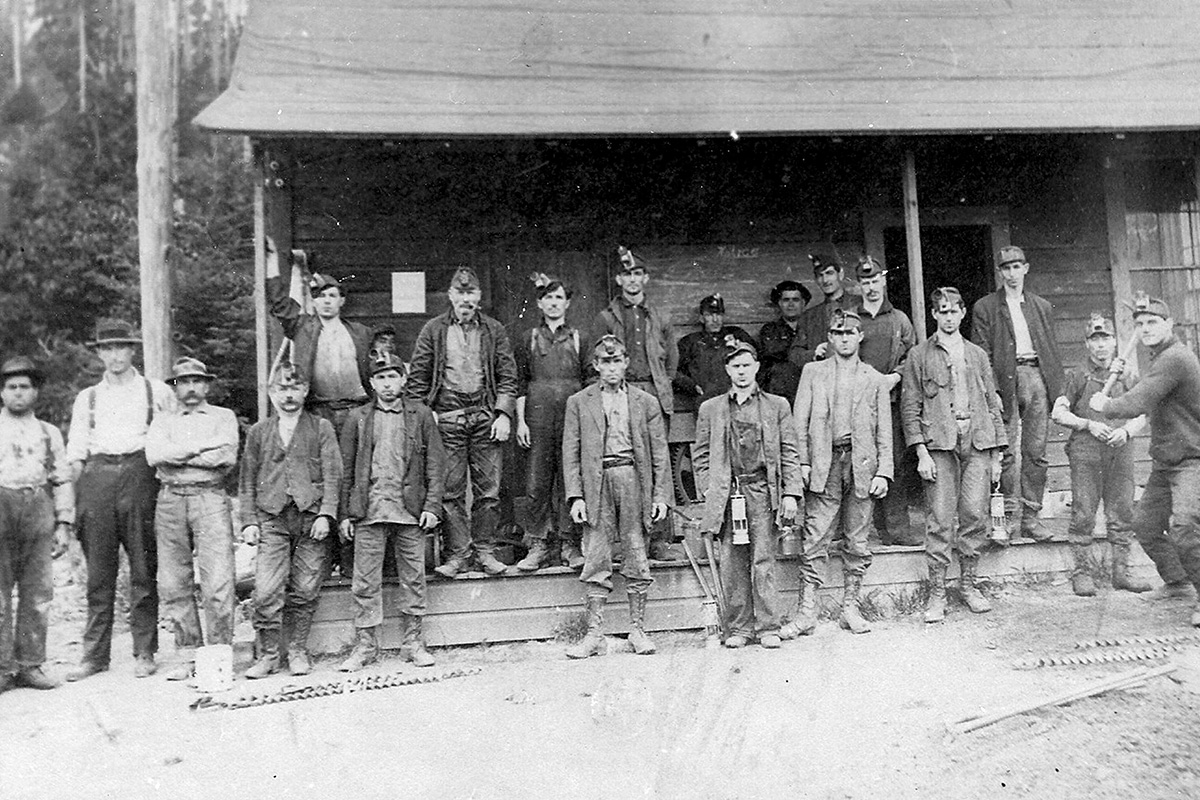

Vancouver Island’s mining communities were predominantly of British origin. The mid–Island region was home to new immigrants who had crossed the Atlantic ocean in search of a better life in North America. Many of the British and other European immigrants brought with them militant traditions and the ideas of trade union organization and socialism.

The mining communities were tight-knit, but anti-Asian racism had poisoned the Island. The Island was also home to a significant Chinese population. Some of the first Chinese immigrants had arrived on the Island during the gold rush period in the mid-19th century. The majority of the first Chinese immigrants came from southern China during the late 19th century to build the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) as indentured workers. During the construction of the CPR hundreds of Chinese workers perished.

Source: University of Washington, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The appalling conditions the Chinese workers were forced to work under led to numerous strikes by Chinese workers. But these workers were isolated and as a result these strikes were ruthlessly put down by the ruling class. Chinese workers also took part in many strikes and union drives led by white workers but were deliberately excluded by the labour leaders. Shamefully, the trade unions at the time had fallen into the trap the bourgeoisie had set for them and refused to organize Chinese workers into the unions. The labour movement had adopted an opposition to immigration and immigrant labour in order to protect the wages of the white workers. In reality, this was due to the rampant racism fomented by the ruling class. This was a reaction by the union leaders to the “race to the bottom” of the bosses to keep wages low. Instead of fighting for the inclusion of Chinese workers in the trade unions and fighting for better wages and conditions for them too, many labour leaders continuously pursued an anti-Asian policy.

At the time, the Vancouver Island mines were some of the most dangerous in the world. Miners were maimed and injured in the mines on a daily basis. In the three decades preceding the Great Strike at least 373 men were killed in the Vancouver Island mines. A gas explosion at the Vancouver Coal and Land Co. mine in 1887 led to the deaths of 148 miners. Another explosion in 1909 killed 32 miners. The families of the men who were killed and maimed in the mines were forced to rely on donations and relief funds as well as their own earning capacity to get by. These experiences led the workers on the Island to rapidly develop class consciousness, and even pushed many of them in a revolutionary direction. In the words of Marx, this is how the working class transforms from “a class in itself” to “a class for itself.”

One of the characterizations of the early development of Canadian capitalism were “company towns”, privately owned towns by bosses which became explosive sites of class struggle. The hated mining boss, James Dunsmuir, or “King Jamie” as he was called by the miners, owned half of Vancouver Island through a “land grant”. Dunsmuir, who was born into the coal fortune of his family, even took office as Premier of British Columbia and then Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia to secure his interests and ensure the suppression of the workers’ movement and rights.

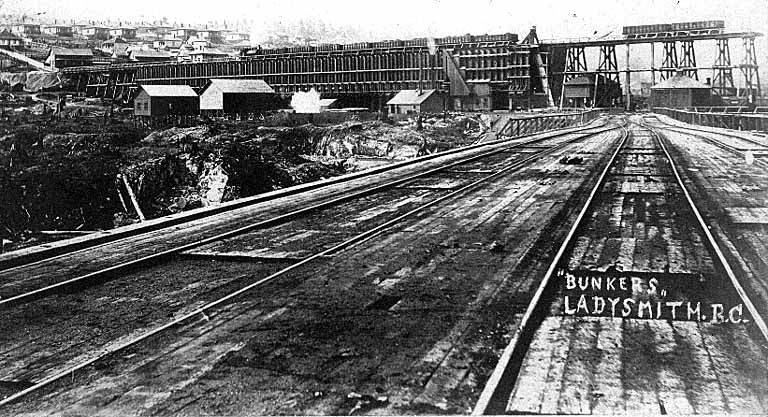

In 1898, Dunsmuir founded the town of Ladysmith (initially named Oyster Bay) and forced his workers to move to the town to keep trade unions out. Ladysmith and the other “company towns” also had company stores in which the workers had to buy everything they needed to work in the mines. The prices of the tools and equipment the miners were dependent on were highly inflated. This meant the miners were doubly exploited: in their wages and in their purchases.

The Dunsmuir mines were operated in Extension, Ladysmith, Ladysmith proper, and Cumberland which Dunsmuir sold to the Canadian Collieries Ltd. company (CC (D)), owned by the equally notorious railway bosses Mackenzie and Mann., financed by British capital, in 1910. While the other mines operated in Nanaimo, South Wellington, were owned by the Western Fuel Corporation, the Pacific Coast Company and the Vancouver and Nanaimo Coal Company.

The precarious conditions of the miners were further compounded by the “court-house” system the bosses had in place. The “court-house” system meant the miners were paid according to the “degree of difficulty of mining coal.” In addition, if rock was detected in the coal, the miner was docked a certain amount of his wages; if too much rock was detected, the miner was not paid.

A majority of the miners rented homes owned by the company and even miners who owned homes had built their homes on company-owned land. The company towns gave the bosses enormous power over the workers. The bosses were able to control nearly all aspects of their lives and regularly used this power to pressure workers to back down and crush strikes and union drives.

Despite the level of repression, the Island was wracked by strikes. There were at least a dozen strikes in some or all of the Island mines before the Great Strike in 1912. Dunsmuir had personally called in the militia in at least three strikes in 1877, 1883, and 1890-91 to crush the workers and force them back to work, feeding into the process of radicalization taking place on the Island.

Trade unions

This radicalization expressed itself both on the political front and the industrial front. In 1903 the first SPC members were elected to the British Columbia Legislature. When the miners’ strike started in 1912, Nanaimo and Newcastle, which included Extension, Ladysmith and South Wellington, were represented by the socialists John Place and Parker Williams, respectively, in the Provincial Legislature.

In 1902 the Nanaimo Miners’ Association voted to join the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) followed by the workers at Dunsmuir’s mines in 1903. The WFM was an industrial union founded in the United States in the late 19th century. The WFM has a rich history of militancy and would play a fundamental role in the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) a few years later in 1905.

Source: www.wfmhall.org (file), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The turn towards industrial unionism terrified not just the mining bosses, but the entire ruling class. They were all determined to prevent industrial unionism from gaining a foothold in Canada. The miners were seen as the vanguard of the working class and as the most militant trade unionists. For the bosses, defeating them was critical to preventing the spread of militant trade unionism. Dunsmuir fired all the workers who attended union meetings and unleashed a campaign of intimidation, proclaiming that the WFM was controlled by “foreign interests” attempting to undermine Canadian industry. The bosses brought in scabs and Chinese workers to continue production. The long streak of defeat the miners suffered in their attempts to unionize continued. The WFM eventually disbanded and left the Island. The bosses then blacklisted the union in the Vancouver Island mines.

The miners drew many lessons from the defeat as their class anger accumulated and in 1910 turned to the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to take on the mining bosses. The UMWA had been established through the merger of the coal miners’ assembly of the Knights of Labor and the National Federation of Miners. The industrial union organized everyone who worked in coal mining. The UMWA quickly became one of the most powerful unions within the AFL. It also became one of the largest unions in the United States; its membership quickly rose from 10,000 in 1897 to over 353,000 in 1912.

The UMWA initially refused the invitation of the Vancouver Island miners on the grounds that they “need to see enthusiasm for unionization.” The leadership was most likely concerned about leading such a militant rank and file and of taking on the Island mining bosses.

The union drive was led by a group of SPC members who worked in the Island mines including George Pettigrew, David Irvine, and Oscar Mottishaw of Ladysmith and John McAllister and the great Joe Naylor of the Cumberland mines. Naylor had started working in the notorious coal mines of Wigan, Lancashire in Britain as a boy, and emigrated to North America, working the mines in Montana, before arriving at the Cumberland mines in 1909, bringing with him revolutionary ideas. Upon his arrival, he joined the SPC, becoming secretary of the Cumberland branch and led the union committee which was initiated by the Ladysmith miners, to organize the Vancouver Island mines. He quickly caught the attention of the Canadian authorities and earned the title “socialist” and eventually a spot on a list of “chief agitators in Canada” compiled by the federal government.

Naylor, along with a group of SPC members, including activists Ginger Goodwin and Jack Kavanaugh, who were not miners at the Island mines at the time, played leading roles in helping with the union drive which was carefully carried out in secret as union drives were all but illegal at that time. Together the activists were elected to positions in the B.C. Federation of Labour, taking over the labour leadership in the province and cementing their names in the history of the Canadian labour movement.

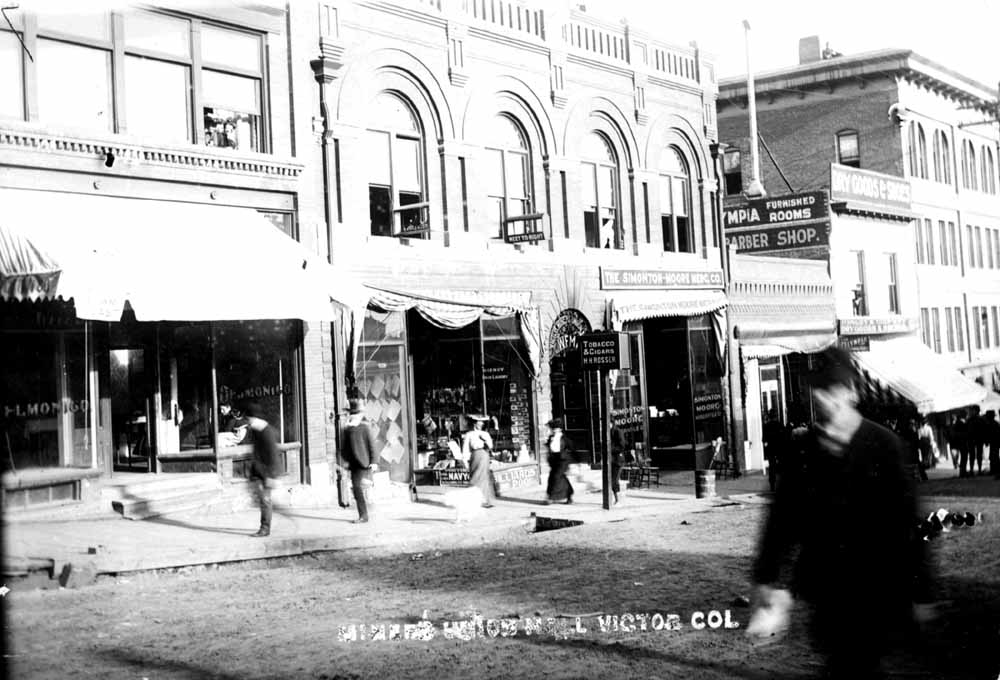

The ruling class pulled out their usual tricks to stop the union in its tracks; a campaign of intimidation and harassment against the union members and organizers was rolled out. The Cumberland city council tried to prevent the union from collecting union dues inside the local bank where the miners were paid. Public street meetings were prohibited and public bandstands had been removed because they were used to hold union meetings. But all the tactics of the ruling class failed, and on December 5, 1911 District 28 of the UMWA was formed.

Lockout and strike

The stage for the strike was set and in September 1912 all the build up of discontent and class anger of the miners exploded. In June 1912, Oscar Mottishaw, one of the leading UMWA organizers, reported gas at the deadly Extension mines in Ladysmith along with fellow miner Issac Portrey. The bosses fired Mottishaw. The unemployed miner managed to find a job as a mule driver at the Cumberland mines, but once bosses found out who he was, he was immediately fired again.

The miners called a meeting for the same day, packing the local theatre on September 15, 1912 and unanimously voted to take a “one-day holiday”, which was done to avoid arrest as strikes were illegal, to demand the reinstatement of Mottishaw. When they returned to work on the 17th, the bosses had posted a note at the mine ordering the workers to remove their tools from the mine, effectively locking out the workers.

Source: University of Washington, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

News of the lockout reached the Extension mines in Ladysmith, and the next day miners there downed tools and walked off the pitheads declaring a “one-day holiday” in support of the Cumberland miners. When the Extension miners returned to work the following day, they too had been locked out. The Great Strike had started.

The Chinese and Japanese miners also walked off the job. The unity of the workers was remarkable. The workers instinctively broke through the racist barriers the ruling class had erected and fostered for so long. The Asian miners allowed the white miners access to their quarters and the workers freely interacted with each other. The company offered the Asian workers a wage increase of $1 per day to return to work in order to break the strike. The Asian miners refused and declared that they would remain on strike with the white miners.

A spontaneous sympathy strike by rail workers erupted. Unionized railway workers refused to handle coal cars that were loaded by scabs. The engineers and fire bosses at the company, maintenance workers in charge of examining the mines for poisonous and explosive gasses before shifts, also walked off the job in support of the miners. But the leadership of the UMWA failed to take advantage of this situation.

Instead of organizing the Asian workers and coordinating with the other unions to mobilize the full force of the workers to put the ruling class on the backfoot, the UMWA leadership sought negotiations and agreements with the ruling class. In their search for “remedies” from the government, the UMWA District President Robert Foster and Christian Sivertz, president of the B.C. Federation of Labour, repeatedly contacted the premier, Richard McBride, who also served as minister of mines and who had served in Dunsmuir’s cabinet when he was in office as Premier, for government intervention.

The leadership also asked the government to investigate the interference with the Gas Committee as per the Coal Mines Regulation Act. The elected socialists, Parker Williams and John Place, tabled a resolution in the Provincial Legislature asking for government intervention in the strike. Williams asked to have a select parliamentary committee appointed to investigate all the issues between the Canadian Collieries Co. and its employees.

Needless to say, the resolution was voted down, with only Place voting in support. While Williams, on the right wing of the party, was most likely motivated by his intention to hold back the workers for the bosses, these attempts by the leadership proved that they failed to understand the role of the state. Any kind of “investigation” or “committee” led by the government, whether through parliament or the courts, was always going to favor the bosses, because this is ultimately the purpose of these entities. These entities were used to crush the strike, they were never going to be used in the interests of the miners.

The mining bosses and government, which took a “special interest” in the extremely profitable industry, refused to even meet with the union; they were determined to bring about a showdown with the workers and the union. The bosses were hellbent on defeating the workers, lest they herald the entry of industrial unionism and threaten their profits and share of the world market.

Class war

The ruling class declared war on the workers. Several of the union officials were arrested and charged for “inducing the company’s employees to break [their] contracts”.

The bosses immediately served the miners renting company-owned houses and on company land with eviction notices. At least 100 families were evicted in Cumberland and Bevan. The miners and their families were forced to set up tents and build shacks at what came to be known as Strikers’ Beach at Royston along Comox Lake.

Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The government sent in “special” provincial police to Cumberland and they immediately surrounded the Asian quarters, preventing the Asian and white workers from interacting with each other. Within a few days the Chinese and Japanese workers said they wanted to return to work. The CC (D) general manager, William Coulson, with the police by his side, went to each of the Asian workers and threatened them with deportation unless they returned to work. The Asian workers were then forced to sign a two-year contract with the company.

The “special” police were hastily recruited from elements of the lumpenproletariat, the most downtrodden, disorganized and backward elements of the working class which Marx described in The Communist Manifesto as “the ‘dangerous class’, [lumpenproletariat] the social scum, that passively rotting mass thrown off by the lowest layers of the old society.”

These “specials” terrorized the mining communities, harassed the women, and attempted to provoke the miners into violence. Many of them were eventually deemed “unfit for duty” and discharged after they had been sent into the mining communities. Throughout the strike the bosses were unable to rely on the local police as they tended to be more sympathetic to the miners and had to bring in more and more special and provincial police to protect scabs and company property.

The engineers and fire bosses were enticed back to work too. Scabs were brought in from eastern British Columbia and Alberta and the government sent more special provincial police as well as (regular) provincial police from Victoria to protect them.

The bosses then unleashed their allies in the press. The bourgeois press launched a massive assault on the UMWA and AFL to turn public support against the miners and break the union: the UMWA was labelled an “outside force” composed of “foreign agents” and “foreign agitators” trying to damage Canada. Bourgeois headlines lied about production levels and the number of scabs to break the spirit of the miners.

There were multiple attempted bombings of the Trent bridge, which was used for transporting coal, but the bombs failed to go off. The bosses blamed the miners; the miners denied any involvement. The stories of the bosses were discredited when their version of events did not add up. Needless to say, the miners worked with dynamite everyday; if they wanted to blow up the Trent Bridge, they would not have failed.

Not only did the bosses fail to break the strike and the spirit of the miners with their usual tactics, the workers rose to the challenge and waged an equally determined counter-offensive. The miners displayed remarkable unity and militancy. They were determined to break with the defeats of the past.

Initially, the miners worked as individuals or in small groups to defend their pickets and stop the scabs. But when the bosses brought in more scabs and special provincial police to protect them, the miners began to work in larger groups with their families. Groups as large as 500 miners and supporters would “escort” the scabs to and from the pits, playing loud music (an age-old tactic of “charivaris”). The miners would march through the town singing the Marsellaise, and flying red flags as a sign of workers’ power.

The role of women

The wives, daughters and sisters of the miners played a most militant role which reflected the radicalization of women in the mining communities. Many of the women were members of the UMWA’s Women’s Auxiliary. They held informal political education discussions, organized weekly strategy meetings, planned protests and demonstrations, and raised much-needed funds for the union and the families of the miners. The women joined the picket lines too, defending the lines with the miners.

The women also took to the streets, forming a section of their own in the marches, headed by a band composed of accordionists, a fiddler, and a trombone player, all the while raising militant slogans. Many women also took on work outside the home to help their families survive and even organized childcare services and set up soup kitchens.

The wives of the coal miners in particular earned a reputation of their own for harassing the scabs and the police. The bosses, terrified of the politicization and display of militancy by the women, which was accompanied by growing agitation for women’s suffrage, charged and fined a few women for their role in the strike, with the presiding judge and authorities warning them they “risked losing the respect of their husbands” with such “unlady-like” behavior.

The women spoke to a local paper illustrating their determination not to back down: “Wouldn’t you fight, and starve if need be, if when your man left the house you didn’t know how he was coming back?” Another woman spoke of the trauma and anger the 1909 explosion had left in the mining communities: “You don’t forget when you see 30 graves, all new, dug in a row waiting to be filled with men you’ve known all your life”.

The women also earned a reputation for coming up with creative ways to sustain the morale of the miners, as a local paper described it: “sparing no effort to plan and scheme innocent diversions to keep their menfolks in good humor”. They organized socials, events, and festivals. Without the tremendous sacrifices of the women, the miners most certainly could not have fought for so long.

Union leadership

While all this was underway, the union leadership sat on the sidelines. They failed to organize and guide the militancy of the workers and instead were attempting to hold back the workers.

When the Asian workers were forced back to work, the union leadership did nothing. In 1907, the UMWA in the US had officially opposed exclusion and had even begun recruiting Asian miners. However, the decision to include or exclude Asian workers was ultimately left up to the individual locals. Upon inviting the UMWA to the Island mines, Joe Naylor applied to the international to bring in a Chinese speaking representative to help organize the Asian workers but the international denied the request. While the leadership of the UMWA initially welcomed the display of solidarity by the Chinese and Japanese workers, they did not organize them and watched as they were threatened with deportation and forced back to work.

As the strike dragged on, the leadership learned nothing. At the 1914 convention of the B.C. Federation of Labour, Thomas Jordan of Nanaimo Local 2824 of the UMWA successfully proposed a resolution for “the total exclusion of Asiatics from this dominion”. Jordan supposedly did not object to the inclusion of Asian workers because of their race but because “they were serious competition to white labour”. Naylor spoke to the B.C. Federation of Labour in defense of the Asian workers, after stating that he was under instructions from his local to vote for the exclusion of Asian workers. He came out against his own local, but he was isolated. The need to build unity with the Asian workers had become clear. Countless previous strikes had gone down in defeat with the bosses making use of Asian labour to resume production during strikes, but the leadership refused to learn from these lessons and drowned in their racism.

It is the task of the workers’ leadership to organize the workers along class lines, to bring workers of all backgrounds into the struggle, and bring out the real common interests that all workers share against the bosses. The ruling class deliberately fosters racism to divide the working class and prevent the workers from uniting along class lines, because a united workforce is a threat to the rule of the bosses. The only way the workers can win their struggles is by uniting against the bosses.

The UMWA’s failure to unite and coordinate the workers also left a vacuum which allowed the CC (D) to scheme in order to bring the engineers and fire bosses back to work. Like the miners, the engineers and fire bosses were fighting for the right to trade union representation. In August, the engineers had joined the British Columbia Association of Stationary Engineers, and fire bosses also formed a union of their own, but the CC (D) refused to recognize their unions. Seeing the potential power that lay in the hands of the engineers and fire bosses, the company offered them a 20 per cent increase in wages and even agreed to recognize their unions to crush the miners. It was the leadership’s weakness that allowed the bosses to successfully employ their divide and conquer method to weaken the movement.

Crucially, while the Cumberland and Extension mines were struck, the mines in Nanaimo on Vancouver Island and the mines in Washington State, which the UMWA represented too, were not struck.

The CC (D) had resumed partial production with the Asian workers and scabs. The remaining shortage of coal that was caused by the strike was being supplied by the Nanaimo mines and imports of coal from Washington State. In fact, the importing of coal from Washington State was increased to meet demand. As long as the Nanaimo and Washington State mines were not struck, the bosses did not have to fear losing their share in the market.

Under pressure from the rank and file, the union threatened to call sympathy strikes in both Nanaimo and Washington State. For the leadership this was only an empty threat, designed as a warning to the bosses of the determination of the workers if the bosses would not back down and bring them to the negotiating table. The leadership mainly wanted to use this empty threat to allow the workers to blow off some steam. The ultimate idea of the leadership was to appear militant in order to buy time to slow down the workers as they sought negotiations with the ruling class. But the pressure from below only increased. The miners increased the size of their pickets and escalated their tactics.

The ruling class was in a panic. They had failed to crush the strike and the union leadership had failed to hold the workers back. Attorney General William Bowser, acting as Premier in the absence of McBride who was away on a trip to London, England, sent in an additional 100 special provincial police to crush the strike. But this only served to expose the real role of the state under capitalism to any of the workers who may have been confused, and fed into the process of rising class consciousness.

Source: City of Vancouver Archves, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

“It is no longer the Canadian Collieries Co. that the strikers have to fight at Cumberland. It is the McBride government direct. The miners have the company sewed up… But the coal barons, realizing this, have called upon the provincial government to take a hand” wrote the miners who took to the B.C. Federationist, the B.C. Federation of Labour’s paper, to respond to the ruling class. More articles followed, titled: “Thug rule in strike zone only strengthens determination to win” and “Special police-ruled strike fails to break spirit of miners.”

The special provincial police had surrounded all the mines and were transporting the scabs to and from the pits. The bosses were now attempting to resume production at the Extension mines in Ladysmith. Initially, the bosses had refrained from reopening the Extension mines and put all their efforts into breaking the strike at Cumberland. The bosses calculated that once they crushed the strike at Cumberland, the strike at Ladysmith would collapse. They miscalculated.

The miners began to mobilize in larger groups to stop the scabs and fight off the cops. But while the workers were displaying militancy, the leadership was attempting to restrain the workers. Joe Naylor and John McAllister, the strike leaders and the leading union members with the most authority, warned the miners against participating in demonstrations against the scabs and even told them to stay home! At a union meeting in Ladysmith two of the local leaders on the international executive even threatened the miners, indicating that the international would withdraw its support from the union if the miners did not “obey the law” and refrain from demonstrations!

This encapsulated the weakness at the top of the strike movement. When these leaders were put to the test, they retreated. These leaders were afraid of the consequences and as a result they could not lead the strike forward.

The ruling class was accusing the miners of violence when the bourgeois state is nothing but organized violence. What they actually meant was that the miners dared to defend themselves and fight back. The violence came from the state which was attempting to starve the miners and their families into submission to protect the profits of the coal barons. We are told that the state is neutral – that the courts, the military, the police, and the media are all independent entities acting in the interest of all classes in the name of “democracy” and “the rule of law”. Yet, from day one the bosses used all means of force at their disposal against the workers–with the B.C. government at their behest.

The bosses attacked the right to strike and unionize in the name of “the law”. The government and police protected and defended the scabs who were destroying the livelihood of the miners in the name of “democracy”. The courts upheld the demands of the mining bosses, refusing to recognize the right to trade union representation, criminalizing the right to strike, evicting the miners from their homes, and threatening the Asian workers with deportation–all in the name of “the rule of law” and “democracy”.

The media bombarded the masses with the bosses’ propaganda in the name of “democracy.” The strike made crystal clear that behind the law, democracy, the courts, police, and media lies the rule of capital. It is through these entities that the ruling class enforces its political power to suppress and contain the working class. In the final analysis, in order to ensure the rule of the capitalists, the state needs a monopoly on violence. Special armed bodies of men, i.e. the police, the military, etc., are organized to defend the interests of the ruling class.

It is the task of the trade union leadership to strengthen the workers; to raise their political level so that they understand the forces that confront them and to prepare the ground for battle. Instead of leading a militant struggle, the leadership attempted to restrain the workers every step of the way as the ruling class unloaded every weapon in their arsenal against the workers.

But to the dismay of the leadership, the pressure from the rank and file was so immense the leadership could not contain them and were forced to move. The UMWA leadership held an executive meeting in which they decided they would declare a general strike of all mines on Vancouver Island “in an endeavor to influence the government to intervene but to carry out this program only when all other means of effecting a conference” with the bosses had failed. They did this to contain the workers, but when their manouver failed, they were forced to call a strike at Nanaimo.

May Day

The strike call served as a lightning rod for the pent-up discontent and anger of the Nanaimo miners. On April 30, the international posted signs around all the Nanaimo mines calling a strike. The next day was International Workers’ Day, May Day, which inspired the workers and strengthened their resolve.

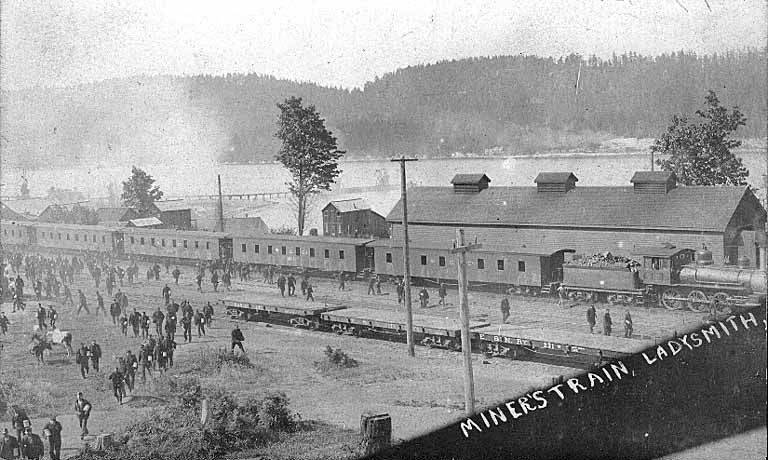

May Day celebrations were organized in Ladysmith. The mood and energy of the workers was electric. Special trains were chartered to bring Nanaimo families to Ladysmith. Over 5,000 miners and their families were in attendance. The 1913 May Day parade was a display of the strength and unity of the miners on the Island.

At the beginning of the May Day parade were the children of the striking miners carrying a banner that read: “The Hope of the Future”. Behind them were the miners and their wives, carrying banners that read: “In union there is strength” and “Workers of the world unite”, as red flags were flown through the workers’ march. A revolutionary spirit had seized Vancouver Island.

The bosses watching the celebrations unfold brought scabs into town and paraded them through the streets to provoke the miners–without success. After the parade about 1500 Nanaimo miners packed the local Princess Theatre and overwhelmingly voted for strike action. Nanaimo was struck. Almost a year after the strike had started in Cumberland, all the mines on Vancouver Island were now on strike.

The union in Nanaimo was small. The Nanaimo mines were owned by the Western Fuel Co. who had developed “a system of espionage” with a network of spies that kept the bosses aware of the workers’ activities. The mere mention of union organization was tantamount to firing. But once the struggle broke out, the miners lost their fear and all the pressure that had built up erupted to the surface.

Within one week after the strike had been called, 95 percent of the workers who were not in the union on May 1 had joined. The fact that Nanaimo became a strong bastion for the strike proved that the strike had moved beyond a fight for unionization and a revolutionary wave had taken hold of the Island.

The spread of the strike to the Nanaimo mines struck fear in the hearts of the ruling class. It prompted the federal government to send a minister into the mines as they scrambled to stop the spread of the strike. The bosses, aided by the government, brought out all their dirty tactics to crush the workers.

Just as the miners in Cumberland, Extension, and Ladysmith had been evicted from their homes, the miners in Nanaimo lost their homes too. The evicted miners moved in with relatives or friends, or into small cottages and barracks they had hurriedly constructed.

The bosses, faced with an all out strike of all the Island mines, were now trying to fully reopen every mine on the Island. They brought in more and more scabs and cops to protect them. In addition to increasing the number of Asian miners and scabs from B.C. and Alberta, the companies brought more than 300 scabs from Missouri and as far away as Durham, England. Those who did choose to work were often housed in the homes of the evicted miners and were protected by a force of special provincial police, which had grown to almost 200 in number. The specials were now acting as “employment agents” and had become increasingly aggressive towards miners and their wives. It was no longer safe for the women in the mining communities to be out past dark because of the cops.

The bosses then armed the scabs. These tactics only hardened the determination of the miners to defeat the bosses. Despite the heavy presence of police at the pitheads, in many instances miners spoke with the scabs and many of the scabs refused to work. The bosses continued to lose their scabs. As more scabs were brought in, the miners split into groups, allotting groups for picket duty and for “escorting” the scabs to and from the pitheads. The miners also continued to organize parades through the streets singing and playing instruments and flying the red flag.

The balance of class forces was still very favorable towards the workers. There was widespread support for the strike across various sectors. The pace of events at Nanaimo indicates the pressure that had accumulated, but it was up to the leadership to spread and coordinate strikes.

Had the leadership coordinated strike action into a mass campaign of united action across the Island with socialist demands, it would have spread like lightning through the region. The ground for a general strike, even a revolutionary movement, had been prepared. Instead, the leadership only flirted with calling a general strike as well as a strike at the Washington State mines to contain the workers. A total of four votes were taken in favour of a general strike but the leadership managed to avert each one. The strike at the Washington State mines was never called.

Divisions in the union

Throughout the strike the local leadership led by Naylor, McAllister, Mottishaw, amongst others came into conflict with the international leadership. While the local leaders were prepared to fight, the international board, led by Frank Farrington, who the union executive in the United States had placed in charge of the strike in place of UMWA president J. P. White, repeatedly came down on the local leadership to restrain the workers in the name of respecting the law and “non-violence.”

Farrington fought against spreading the strike and the calling of a general strike. He even spoke against a general strike after the mass arrests of the miners in 1913 at a Vancouver Trades and Labour Council saying: “I don’t regard the men who are now under arrest for rioting at Nanaimo as martyrs at all. I regard them as fools who had not sense enough to keep their mouths shut. Now some of these fellows think it is fine to get in the limelight. They are envious to get their names in the paper and be cheered as heroes, but as a matter of fact a man behind bars is not doing very much to help the cause.”

Source: Asahel Curtis, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The right wing of the union, backed by the international board, was openly attempting to collaborate with the ruling class to bring an end to the strike. They consistently voted against spreading the strike to Nanaimo, to Washington State, and against a general strike. The right wing had adopted a philosophy of class collaboration, attempting to reconcile the irreconcilable class contradictions that exist under capitalism. These leaders, who wanted to secure a cozy relationship with the bosses based on a model of what would become known as “business unionism”, had sold themselves out long ago.

The left wing of the union, as sincere and as radical as Naylor and the others were, lacked a consistent program and perspective, and as a result came under the pressure of the international and the right wing and eventually capitulated. Consequently, instead of preparing a militant movement, by fighting alongside the workers in their struggle and linking it to the struggle for socialism every step of the way whilst drawing in ever-wider layers of the population to a revolutionary program, they were looking to make compromises with the bosses too.

Ultimately, it is the political and theoretical weakness of the left wing that make them unable to show a way forward. These sincere leaders could not break away from the old, conservative traditions of passivity and submissiveness because of past defeats. As a result, they could not see the mood that had been built within the rank and file. When in reality, the explosive mood that had erupted from below only needed direction.

The left-wing leadership played by the rules of the bourgeoisie in the hopes that the bosses and the state would “do the right thing.” But the bosses and government did not waver from their determination to crush the union one bit. In fact, each time the workers fought back, the bosses sharpened their attacks.

The UMWA’s entrance onto the Island emboldened the workers. It gave the miners confidence and hope. When their right to trade union representation was attacked with Mottishaw’s dismissal, the miners downed their tools and walked off the pits without consulting the leadership, essentially going on a wildcat strike. They moved ahead of the leadership and forced them to follow their lead. In fact, the leadership had to play catch-up with the militant rank-and-file throughout the strike. The workers showed relentless militancy and determination but the leadership, directly and indirectly, acted as a brake on the strike.

The miners continuously came up against the limitations of their leadership. The rank and file displayed an enormous amount of courage and bravery, coming on to the streets day after day, and taking on the scabs and police. But the leadership of the miners’ strike lacked a clear program, direction, strategy and tactics, despite the fact that they were confronted by an organized unified force that was determined to fight the workers to the bitter end. The UMWA’s inability to show a way forward left the miners open to attacks as the strike dragged on.

August Riots

In one incident, a scab herder was sent into Cumberland with 15 others to “clean out the strikers.” The scabs attacked the miners who fought back. All the miners involved, as well as Joe Naylor who was not even involved in the fight, were arrested and denied bail. The scab herder was only arrested after protests from the miners while the police refused to arrest the other scabs.

In another incident, a group of four scabs confronted two miners who were walking home in the evening and stabbed one of the miners. The miner was left with minor injuries and made a full recovery. But the scab who stabbed the miner was only arrested after protests by the miners while the others were let go by the police. The UMWA leadership was lucky that no miner was seriously injured or killed.

The bosses brought in more and more scabs and special provincial police. The miners showed an immense amount of restraint in the face of daily violence and provocations. They did not fall for the ruling class’s attempts to sabotage the strike. But in the absence of leadership and against the background of daily police and scab violence and intimidation, all the pressure eventually exploded in the “August Riots.”

At dawn on Monday, Aug. 11, 1913, the miners had received news that a large contingent of scabs were being brought into Nanaimo’s No. 1 mine. The miners called a meeting at the Union Hall and passed a resolution: “That if the police do not extend to our members the protection of the law we will be compelled to take measures to protect ourselves” and then headed for Nanaimo.

About 500 miners and their families began picketing the pithead and the street leading to the mine. When a scab, protected by a special provincial police, threatened them with a gun, the miners who had their wives and children with them, left the scene.

The miners returned to the pitheads in the afternoon, with miners from South Wellington. Together the miners, about 700-strong, picketed the No. 1 mine. When the local Chief of Police arrived with a contingent of police to transport the scabs from the pitheads in police cars, the miners finally unleashed their fury. The workers stoned the police cars and smashed the windows, and when the police and scabs tried to confront them, they attacked them and drove them from the scene. More specials were sent after the mayor of Nanaimo sent Attorney General Bowser a telegraph asking for backup.

The miners now took matters into their hands to fight back against the bosses and the state. The strike leaders were not involved in the actions the workers would take over the next few days. In fact, the workers were taking actions against the wishes of the local and international leadership. The actions of the workers showed their fierce determination to win the struggle as well as the potential for victory if the leadership had been willing to harness the energy and fighting spirit of the workers.

The next day, Tuesday, August 12, the miners returned to picket No. 1 with more miners from Extension. More than 1,000 miners picketed the pitheads. When Provincial Constable Hannay arrived with a contingent of specials to transport the scabs home, the miners attacked the police cars and drove the cops away. Without the protection of the police, the scabs were so afraid they remained in the pits until late evening when the miners finally returned home.

The miners in South Wellington had had enough of the scabs and police too. After being joined by some from the Nanaimo mines, some 800 miners marched through South Wellington. They drove out the special police and then attacked the carpenter’s shop, where the scabs were being housed. They drove out the scabs, and then attacked the Chinese bunkhouses, driving the Chinese strikebreakers out of town. Then they smashed the windows and doors of company property.

In the early hours of Wednesday, August 13, an explosion was heard at the Temperance Hotel in Ladysmith, where the imported scabs were housed. Shortly after, a bomb went off in the home of a scab, who was mutilated from the blast. The scab, who had joined the union and drawn strike pay for almost a year before returning to work, was known to regularly attempt to taunt and provoke the miners with bread crusts from his lunch box. The miners were accused of throwing the bomb into his home. They denied any involvement. The miners were only cleared of any involvement the following year when three men, none of whom were miners, were confirmed to be the culprits, most likely provocateurs hired by the bosses.

After receiving news about the events at South Wellington, the Ladysmith miners and their families marched through town at dawn, forming a “peace mission” to signal their intentions. Faced with the intransigence of bosses with their police and scabs, the workers warned the scabs to stop working by going to their homes and telling “each one that if he remained after 12:00 pm August 15 he would not be safe, and that if he wished safety in the interval he must go to the Union Hall and sign a paper”. The bosses continued to lose many of their scabs to the union side.

On Wednesday, August 13, none of the scabs in Nanaimo attempted to work, but the miners soon found out more cops were on their way from Vancouver by boat. About 600 miners headed for the docks to greet the cops. When the boat arrived the miners checked each passenger coming off the boat to see if he was carrying a badge. The miners disarmed all the specials.

In the meantime, another group of miners had gathered a group of specials who had arrived that morning by train from Victoria. The miners had removed their guns, clubs, and badges and were marching them to the dock. Another group of miners moved on to the local police on dock duty, including the local Chief of Police Neen, to disarm them. When they attempted to pull their guns on the miners, the miners gave them a good beating, leaving them with bruises and gashes. Together, the miners herded all of the cops onto the Princess Patricia boat and sent them all to Vancouver.

The miners then headed back into town but made a stop at the office of the Herald, a bourgeois newspaper which had been spewing anti-strike propaganda and plastering the Island with lies about the union. While a large crowd waited outside the office, a number of miners went inside and warned the editor that if he printed an edition the next day, his presses would be dynamited.

At this point, a boy rode up to the Herald office with word that six miners had been killed by scabs at the Extension mines in Ladysmith. It was later learned that this was not true. It was most likely set up as a provocation by the bosses, but the miners rushed out and headed for Ladysmith.

Upon hearing the news, the South Wellington miners headed for Ladysmith too, arriving in Ladysmith before the Nanaimo miners. They met the Ladysmith miners and together demanded that they be given a meeting with the company manager and six of the scabs. J.H. Cunningham, the manager, refused to speak with the miners, who returned to the pitheads to speak with the scabs. As they approached the pits, the scabs started shooting from inside the pitheads. Amazingly, only one person was shot, a contractor who was in town, who caught a bullet in the arm.

On their march to the Extension mines in Ladysmith, the Nanaimo miners broke into a hardware store which supplied guns and ammunition and armed themselves. On reaching Ladysmith, the miners were met by a volley of shots from the scabs. The miners, 600-strong, returned fire and advanced on the scabs. The scabs retreated, some running into the pithead to hide while others ran into the surrounding bush.

The pent up anger and frustration of the miners had briefly erupted with a fury like a wildfire. Together, the miners from Ladysmith, South Wellington, and Nanaimo drove out the remaining police from Ladysmith. Then they drove all the scabs and their families out of town. The miners headed for Chinatown and drove out all the Asian strikebreakers.

Cunningham, the company manager, fled to Port Alberni. The miners set his house on fire. They attacked the property of the bosses. Company property was destroyed. The coal cars used for transporting coal were all destroyed. The miners then attacked the homes of scabs, the homes of the Asian strikebreakers in the Ladysmith Chinatown, and the homes of the engineers and fire bosses. The houses were looted and burned. Cars belonging to the scabs were burned or demolished. Some of the stores were looted and then set on fire.

The town that James Dunsmuir had founded in order to keep workers away from trade unions was now under the control of the workers.

Militia arrives in force

But it is here where the takeover by the workers reached its limits. When the miners took control of the town of Ladysmith, the struggle had moved beyond the usual limits of a strike and trade union organization and had crossed into the territory of an insurrection. The miners controlled Ladysmith, but could not have held onto the town once the military arrived unless they had spread the strike throughout the region and indeed across the country, and connected the struggle with a political program to take over the means of production and ultimately state power.

Many workers across the region and province were sympathetic to the strike, as were many workers across the country and indeed in the United States. But while the struggle had moved beyond that of a strike into a movement with insurrectionary dimensions, this was not necessarily understood as such by the workers. There was no political program or plan for taking power, nevermind maintaining and expanding it.

Once the stores were looted, there was no way to replenish the goods. Once the ammunition was used, there was no way to restock. Unfortunately, courage and bravery are not enough to win such a struggle. The leadership of the workers’ movement must be conscious of its tasks and organize the struggle around a clear political program.

Fifteen hundred armed miners were blocking the road to the Extension mines when a detachment of more than 1,000 militia and government troops armed with Maxim guns, ten thousand rounds of ammunition, an armored train railcar carrying a large field gun, and bayonets came up from behind the miners. The troops had arrived by boat from Departure Bay in Nanaimo.

On August 15, 1913 militiamen from the 6th and 72nd regiments moved into Cumberland and the militiamen of the 88th regiment, supported by a regular army detachment, moved into Nanaimo, South Wellington, Extension, and Ladysmith. The Seaforth Highlanders, the Victoria Fusiliers and the Royal Canadian Artillery occupied all the mines on Vancouver Island. Martial law was not declared as Bowser had threatened, but Vancouver Island was under the complete control of the military.

In removing the police and taking over Ladysmith, the Vancouver Island miners had posed the question of which class should run society, but they were not aware they held this power in their own hands, even if temporarily. The miners did not have a clear or conscious plan to take power. The Island miners could not have resisted the armed forces of the state apparatus, who were better armed, without a political program drawing in other layers of the working class and laying claim to the productive forces.

The scale of the invasion by the military and the weapons dispatched into the small mining communities exposed the true face of capitalism, shattering the mask of bourgeois democracy. But the occupation of the Island failed to crush the union or destroy the miners’ solidarity.

In fact, the miners were strengthened by the mobilization of the entire community as public support of the miners reached new highs. The heavy military presence and the mass arrests brought the labour movement and public out onto the streets. Even the Liberal opposition media came out against the military and arrests, dubbing Bowser “Napoleon Bowser” and calling for the release of the miners. In addition, the miners at the small Jingle Pot mine in Nanaimo had reached a settlement with the bosses, which emboldened the miners that they could force the bosses to come to an agreement on union recognition.

The miners and their wives continued to hold down the picket lines and blocked sidewalks and roads to prevent the militia from getting through and protecting scabs. The militia were recruited by the government from shopkeepers and clerks, but the majority were recruited from the unemployed and lumpenproletarian layers. The militia quickly gained the hatred of the Island.

The feelings of the mining communities and public were soundly expressed by Jack Kavanaugh, vice president of B.C. Federation of Labour at a mass union meeting in Vancouver, that the communities were being “terrorized by half-clad barbarians armed with rifles and bayonets…..No reptile ever evolved from the slime of ages resembles the spawn of filth now on Vancouver Island and known as the militia.”

The support from other layers of the working class was remarkable. Workers at restaurants refused to serve the militia and troops and they had to obtain food by force. The hotel workers refused to allow them a stay and the troops and militia were forced to sleep in railway freight cars without blankets. The telegraph and telephone operators refused to cooperate with the militia. The discussions at meetings between Colonel Hall, the mayor, local Chief of Police Neen, Frank Sheppard, M.P. for Nanaimo, and T.B. Shoebotham, representative for the Attorney General, were being leaked to the striking miners by the phone operators. The offices were seized by the military and the Colonel replaced the telephone workers with military men. But when they realized the operators were tapping the wires in order to convey messages to the miners, Colonel Hall had two of his men from the 72nd Seaforth Highlanders transmit orders in Gaelic!

These militant acts of solidarity proved the struggle of the miners to end their suffering resonated with the majority of the workers on the Island and that the balance of class forces was still in favor of the miners. However, as the leadership took no measures to expand the struggle and to defend the workers from the military, this balance of forces slowed tipped in favour of the bosses and the state.

Mass arrests of the miners were prepared. The troops, with bayonets drawn, surrounded the Athletic Hall in Nanaimo where the miners were holding a meeting in the evening. They pointed a Maxim gun at the backdoor, and drove cars to positions where their lights were pointed at the exits, so that the miners leaving the building would be in the glare of lights and unable to see. The militia entered the Hall, ordering the miners to exit the building and tore the hall apart in search of weapons. Once the miners were arrested, they were marched in groups of ten between lines of troops with fixed bayonets to the Nanaimo Courthouse where they were handed over to the police. Those who were not arrested were kept in the Hall until the morning to prevent their communication with miners at South Wellington, Extension, and Ladysmith.

The remaining troops headed to Extension, Ladysmith and South Wellington to carry out arrests of the miners there, where the workers were pulled out of their beds. In total 213 miners were arrested, 166 were put on trial and 50 were convicted. Although the leadership of the strike was not involved in the events of August, it was used as a pretext to arrest the leading union members. Even Nanaimo MPP, Jack Place, was arrested. None of them were granted bail. Some miners received sentences as long as four years. The charges ranged from rioting to attempted murder, but the true crime of the miners was daring to stand up against the rule of capital.

While in jail the miners composed songs which captured their spirit and unrelenting determination. Attorney-General Bowser and the hated militia were the main subjects:

Run Bowser

Run Bowser run, we will beat you at the poll,

Run Bowser run, we will beat you to your hole,

You thought you could break our spirit,

but you have only hastened the day,

When we’ll make the companies recognize the U.M.W.A!

Another was dedicated to the militia:

Bowser’s Gallant seventy-twa

Oh, did you see the kiltie boys,

Well, laugh, ‘twould nearly kilt you, boys

That day they came to kill both great and small

With bayonet, shot and shell, to blow you all to hell.

A dandy squad was Bowser’s seventy-twa

The Hurrah boys, Hurrah for Bowser’s seventy-twa

The handy dandy candy seventy-twa.

They’ll make the world look small led on by Colonel Hall

Hurrah boys, Hurrah, for Bowser’s seventy-twa

They stood some curious shapes these boys

They must have sprung from apes these boys

Dressed up in Kilt to represent the law

Ma conscience, it was grand, hurrah for old Scotland

And Bowser with his gallant seventy-twa.

They could not stand at ease, these boys

They had no strength, believe me, boys

Some had to stand upon their guns or fall

And many mother’s son had never seen a gun

But mind you, they were Bowser’s seventy-twa

It beat the band to see them land

And make that grand heroic stand,

The emblem of the government and the law.

And we will not forget the day they stormed Departure Bay

Did Bowser and his gallant seventy-twa.

The families of the miners in jail and the remaining miners and their families were experiencing extreme hardships. Their strike relief was not enough to support themselves. The miners who had lost their homes when they went on strike were still living in the tents they set up, or in the shacks, small cottages and barracks they had built in a hurry or still living with relatives or friends.

The sentences being received by the miners shocked the Island. Several protests were organized. This pressure forced the government to release the miners. None of the imprisoned miners served their full sentences. The “ringleaders” Joe Naylor and the other leading union leaders served over four months, while J.J. Taylor and Sam Guthrie were among the last to be released. Joe Angelo, who was the international representative for the “ethnic” workers, was freed last and immediately deported. The miners were released to cheering family members and supporters singing the Marseillaise and flying red flags.

But one miner did not return. Joseph Mairs, a 21-year-old Scottish immigrant, who was arrested for throwing stones at the homes of scabs was murdered when authorities refused him treatment in jail after he became ill with tuberculosis of the intestine. Mairs died of peritonitis on January 20, 1914 at Oakalla prison near Burnaby, B.C., 5 months into his 16-month sentence. His death sent shockwaves across the labour movement, and enraged the mining communities and public.

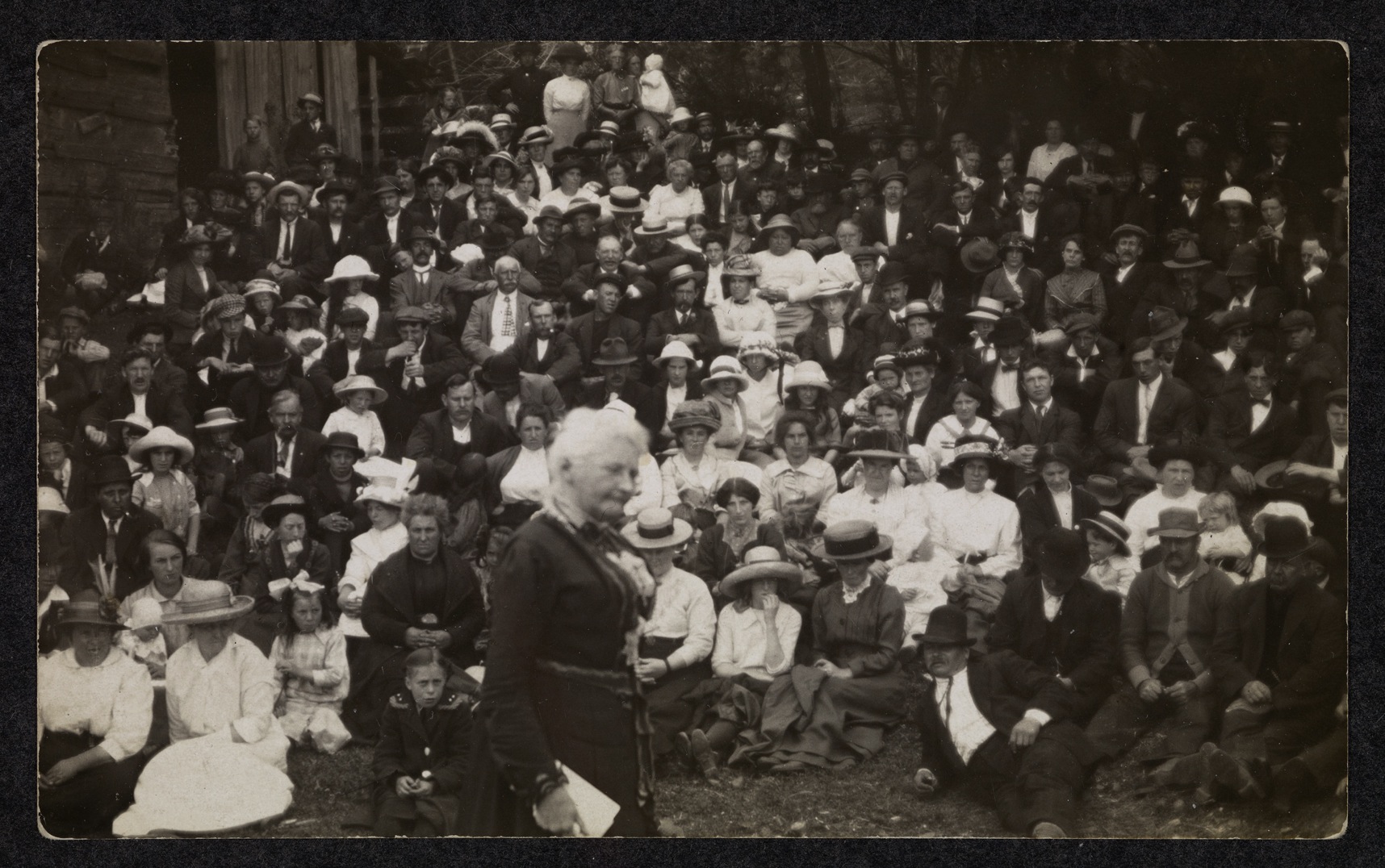

The B.C. Federation of Labour was under tremendous pressure to call a general strike after the arrests, and this only intensified with Mairs’ murder. Even Mother Jones from the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) travelled to the Island in support of a general strike. She gave a series of speeches condemning the tactics of the ruling class and calling for a general strike to crowds of thousands of miners and community members.

community.

Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Federation couldn’t resist the pressure from below and finally agreed to call a general strike. The threat of a general strike terrified the ruling class, and the provincial government was suddenly interested in settling the strike.

The miners, feeling their strength, rejected an offer on the old terms made by the bosses. Like a bolt from the blue, the UMWA announced it would pull strike pay. The union, burdened by the cost of strikes elsewhere, had spent an unprecedented $1.5 million on the Vancouver Island miners’ strike. The international leadership had also become more than fed up with the militancy and radical actions of the Vancouver Island miners. For the international leadership, and all out confrontation with the bosses and the state was out of the question. Within three weeks, the leadership dealt their final blow to the miners; pulling the rug out from under the workers, the international withdrew its support from the local unions and disbanded District 28. The entire Vancouver Island district of the union was dissolved.

World War I and class struggle

The outbreak of World War I played a similar role in the Ladysmith strike as it had in other countries around the world. In the three or four years before World War I, a revolutionary mood had gripped the working class in countries around the globe. Countries such as the United States, Britain, Russia, and Canada saw a marked increase in militant labour action and the stirring of a revolutionary mood among the workers.

This revolutionary mood of the working class was silenced by the outbreak of war. In its place rose a wild patriotic enthusiasm for the war effort. And so the start of World War I in Europe brought plans of a general strike, which was agreed to by the B.C. Federation of Labour in principle, to an abrupt halt. On August 19, 1914, just over two weeks after World War I started, the miners voted to accept the deal offered by the bosses and end the Great Strike.

Despite the heroic actions of the workers and the continued protests, the miners had achieved very little in terms of their demands. The steeled determination of the miners to win the fight had slowly begun to transform into fatigue. The UMWA had withdrawn their strike pay and severed ties with the miners. Groups of newly hired miners had largely replaced the striking workers who had left or been blacklisted. Many of the miners involved in the strike then also volunteered to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force, with many of them perishing in the carnage of the battlefields in Europe.

The miners on Vancouver Island had spent decades fighting for better working conditions, improved safety in the mines, and union recognition. However, this recognition would only come to Vancouver Island in 1938–more than two decades later and 6 weeks after the largest mine on the Island had been closed for good.

The miners and their families were marked for life. They were ostracized in the mining communities. The descendants of the miners to this day remember the names of the scabs and which side families were on. The suffering of the miners and their families was exacerbated by the Great Depression. No work was available and without a social safety net, families were left without an income. The mining communities were left in destitution. Many families left the Island. Some of them returned to Britain. The government was forced to hand out food and introduce a work-for-welfare program on the roads. The mining bosses blacklisted all the leading activists. The CC (D) blacklisted Naylor for 10 years. Naylor remained unemployed for years having to rely on donations to survive.

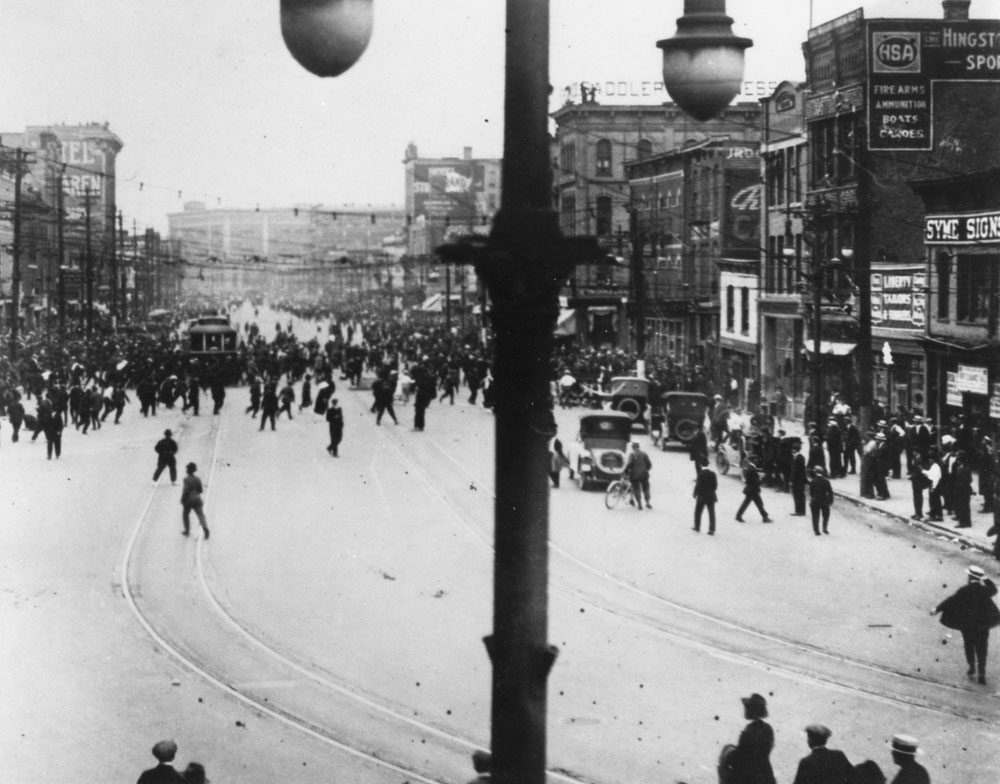

World War I had cut across the revolutionary mood developing amongst the workers. But this mood would return almost immediately upon the end of the war. The Great Vancouver Island Coal strike was a prelude of things to come. Capitalism entered into a period of profound crisis in the immediate aftermath of the war, with inflation causing a rapid rise in the cost of living. Unemployment soared as wartime industries closed. Poor working conditions, low wages, and the refusal of the bosses to recognize unions and workers’ rights fueled the anger of the working class.

The victorious Russian Revolution of 1917 and the revolutionary struggles of the German working class in 1918-1919 inspired a new revolutionary mood among the workers in Canada and the United States. This new revolutionary mood resulted in a series of militant strikes across North America. The year 1919 would go down in history as the year of “Labour Revolt.”

On July 27, 1918, the revolutionary Marxist organizer Ginger Goodwin, who had played an important role in the Vancouver Island Coal Strike as an activist, was shot dead by police after refusing military service. On August 2, 1918, thousands of workers in Vancouver and across Vancouver Island downed tools in Canada’s first general strike. Other significant strike waves would grip Calgary and Edmonton in September 1918.

These strikes in the West in 1918 were a precursor of the great Labour Revolt. In February 1919, workers shut down Seattle with a general strike. A general strike broke out later that same year in Winnipeg, where the strike committee controlled the city for six weeks in May and June.