Part Four: The North-West revolution

An inevitable clash

While thousands of Métis fled west, there was no escaping capitalism. As Marx explained in the Communist Manifesto, “The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe.” Indigenous peoples, including the Métis who played a role in the primitive accumulation of capital which led to the creation of the Canadian bourgeoisie, had now become a barrier to the development of Canadian capitalism.

Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four

The young Canadian state’s actions can be understood in this light. As Marx explained, “The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.” The “common affairs” of the Canadian bourgeoisie in this instance meant the removal of the Métis to make way for mass migration, capitalist agriculture and a railroad to tie the market together. The hunting and gathering economy of the Indigenous peoples was incompatible with the new capitalist world order. A new clash was imminent.

While 1885 is regularly described as the “Riel Rebellion” and is framed as an exclusively Métis movement, this is not true. Pretty much every group had issues with the federal government and there was a widespread movement among all Indigenous groups as well as the white population of the North-West well before Riel was asked to come help lead the movement. Upon his arrival, Riel entered into discussions with some of the First Nations leaders as well as leaders of the white farmers to attempt to unite their grievances into one movement.

For the First Nations, the situation was abysmal. The introduction of the Indian Act in 1876 had the express purpose of “civilizing the Indian,” in order to assimilate them into the capitalist system. Many Indigenous groups were essentially manipulated into signing away their land in treaties and forced onto reserves. There was mass starvation among the Cree, Ojibwa and Blackfoot who had become reliant on government rations. As Jean Teillet pointed out, they were in fact receiving half the rations that prisoners in Siberia were receiving. When pressured to increase the rations, Macdonald, who wanted to keep expenses down, said “the Indians will always grumble.”

For the Métis, the situation bore an eerie resemblance to the situation prior to the movement in Red River. The Canadian state and its laws were technically in effect but no one knew what those laws were and there were limited forces to enforce those laws. Lawrence Clarke, who was the chief factor for the Hudson’s Bay Company in Prince Albert, was technically the official representative of the state. But he was forced to only apply laws selectively, much like the HBC had been doing prior to the events of 1869-70 in Red River.

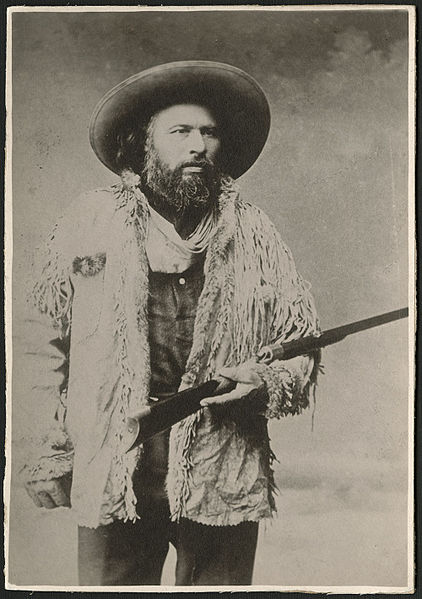

In the vacuum, the Métis of St. Laurent operated by their own set of laws, which were most likely an adaptation of the Red River code or the Laws of the Prairie and elected their own governing councils. At St. Laurent, they elected a council of eight with Gabriel Dumont at its head. This once again placed the Métis in direct conflict with Clarke and the Canadian state which was increasingly attempting to assert its dominance in the region.

The Laws of the Prairie were largely made as a conservation measure and to allow everyone equal access to the buffalo herd. But this goes directly against the laws of the capitalist market which by its very nature is anarchic and against any collective interest. This led to a situation in the spring of 1875 where an HBC employee, Peter Ballendine, tried to take a group of people off to hunt the buffalo prior to the beginning of the official hunt.

Dumont took an armed group and informed them that they would have to join the official hunt and if they did there would be no punishment. Ballentine said that they would not submit to the authority of the St. Laurent Métis Council. Dumont therefore confiscated their equipment and imposed a $25 fine.

In response to this, Clarke charged and fined Dumont and his men and forbade him and the Council of St. Laurent from imposing their law in the region. He instead sent out professionals to hunt the buffalo ahead of the Métis hunt. The meat was appropriated and sold in HBC stores to the new police detachments stationed at Fort Carlton and Duck Lake. The result of this was a Métis famine as the buffalo hunt was undermined.

The situation was also quite dire for many white settlers, poor farmers and workers who felt lied to and betrayed by the Canadian government. They had similar complaints about the despotic nature of the lieutenant-governor’s regime in the North-West which was not responsible to the people. The general demands of the movement were for lowering tariff rates, canceling the CPR monopoly and for provincial status with elected parliaments.

The main leader of the movement among the white settlers was William Henry Jackson (Honoré Jaxon). Jackson along with others helped to organize the Settlers’ and Farmers’ Unions throughout the North-West. They worked in close alliance with the Métis and First Nations peoples’ movements and Jackson even became Riel’s secretary as he went on a speaking tour. Jackson was an admirer of William Lyon Mackenzie who led the uprising in 1837 against the ruling oligarchy in Upper Canada. He also ran a revolutionary paper called The Voice of the People, to compete with the capitalist press and push for social and economic justice for Indigenous peoples and white settlers alike. As a side note, he went on to become a socialist and labour activist.

Far from being simply a Métis affair or something created by Riel, the movement which began in 1884 was a broad movement of all peoples in the North-West against the Canadian state.

The 1885 revolution

Macdonald’s 1882 colonization scheme became a big problem for the Métis on the South Saskatchewan River. A clique of Conservative Party members organized in the Prince Albert Colonization Company had been given the land which dozens of Métis families lived on. This was the single most important factor which drove the Métis forward.

The Métis in St. Laurent had seen this all before and were not about to give up without a fight. Once again, the Métis sent the Canadian government petition after petition to try to find a peaceful solution to their problems but to no avail. Between 1878 and 1885 they sent 84 petitions to Ottawa and unsurprisingly received no response.

This led to the situation in 1884 where the Métis council of St. Laurent met with the Farmers’ Protective Union and drafted a letter of invitation to Riel for him to come back and lead the movement. On the outskirts of Batoche in June 1884, 70 Métis men and women greeted Riel.

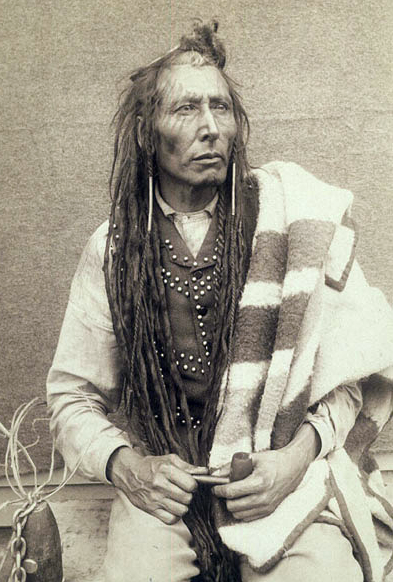

The situation was similar with the Indigenous peoples on the western plains who had been forced to sign bogus treaties which the government was not honoring. This desperate situation led to many chiefs, who had previously signed treaties, to start to mobilize against the Canadian government. As Howards Adams explained: “By the spring of 1884, the economic conditions of the Indians were so serious that Chief Poundmaker called an assembly of Indians of the Northwest. He claimed that Indians realized they had made a serious mistake in agreeing to treaties with the federal government. Superintendent Crozier of the Mounted Police attempted to arrest the Indian chiefs for assembling, but they were so desperate that they defied Crozier’s authority.”

Upon his return, Riel spoke to crowds of hundreds who had come from far and wide to hear him speak. Riel drafted petition after petition putting forward the grievances of the Métis, First Nations and white settlers.

In an incredible sign of solidarity, on July 28, 1884, the Farmers’ Union released a manifesto through their secretary, Honoré Jaxon. This manifesto appealed for unity, for elected legislatures of the North-West and warned about legislators “liable to have their judgement warped by such private interests.” We can see here the developing socialist critique.

The Farmers’ Union manifesto finishes by underlining the strong sense of unity at the time in the face of the divisions sown by Macdonald and the Canadian ruling class: “Louis Riel of Manitoba fame has united the halfbreed element solidly in our favour.” And it continues by saying that “Riel has warned them against the danger of being separated from the whites.”

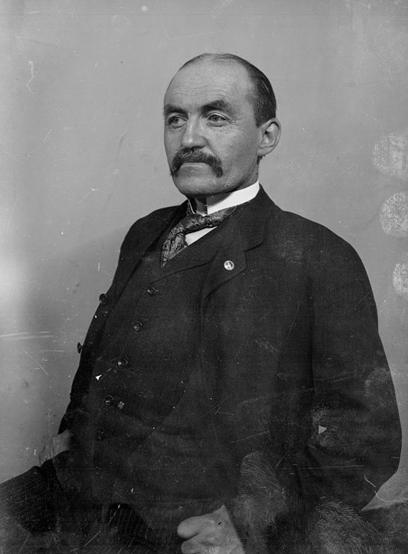

To attempt to counter this, the priests, the police, Macdonald and Edgar Dewdney all conspired to undermine the unity that was being forged, as they had done in 1869-70. In this they had the service of the media which helped them to mollify resistance to their plans. This was the case in Manitoba where Schultz had control of two of the main newspapers, as well as in Prince Albert where John A. Macdonald himself had assumed financial control of the main paper in the settlement in 1884. Through the press the Canadian capitalists put out propaganda warning white settlers about the First Nations and Métis uprising to justify recruiting to the police forces in the region.

The war begins

On March 5, 1885, the Métis voted to take up arms if necessary. The government was starting to worry. Their greatest fear was that the different First Nations groups, the Métis and the white farmers would join forces. This was a real possibility.

On March 8, the Métis council adopted a new Bill of Rights, this time dubbed the “Revolutionary Bill of Rights.” While there wasn’t anything particularly radical proposed in the bill of rights—for example, no revolutionary break with Canada or Britain as happened in the American Revolution—you can tell that the mood at the time reflected itself in this way. This bill of rights was essentially revolutionary in the bourgeois democratic sense, and in Canada at the time this was significant. The bill of rights demanded elected legislatures in the North-West, land possession rights for the Métis and white settlers who had settled and started farming, just treatment of the First Nations, resources and land set aside for hospitals and schools etc.

On March 18, Lawrence Clarke returned from Ottawa and informed them that armed men were coming to arrest Riel and Dumont. Faced with this threat, at a meeting of 300, the Métis voted to take up arms against the Canadian government once again. They proclaimed a new provisional government and appointed a council of 15 with Riel at the head and Dumont as general. They demanded the surrender of the nearby Hudson’s Bay Company post at Fort Carlton. In response, the lieutenant-governor of the North-West Territories, Edgar Dewdney, increased the police forces in the region. In his opinion, “the sooner they [the Métis] are put down the better.”

Leif Crozier, the newly appointed North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) superintendent and commander of North-Western Saskatchewan’s forces, rejected the demand to surrender Fort Carlton and requested reinforcements. On March 25 Crozier, who needed supplies for his men, ordered them to procure supplies at the general store in Duck Lake. Little did he know that Dumont was already occupying the town, as he had been dispatched to get supplies as well.

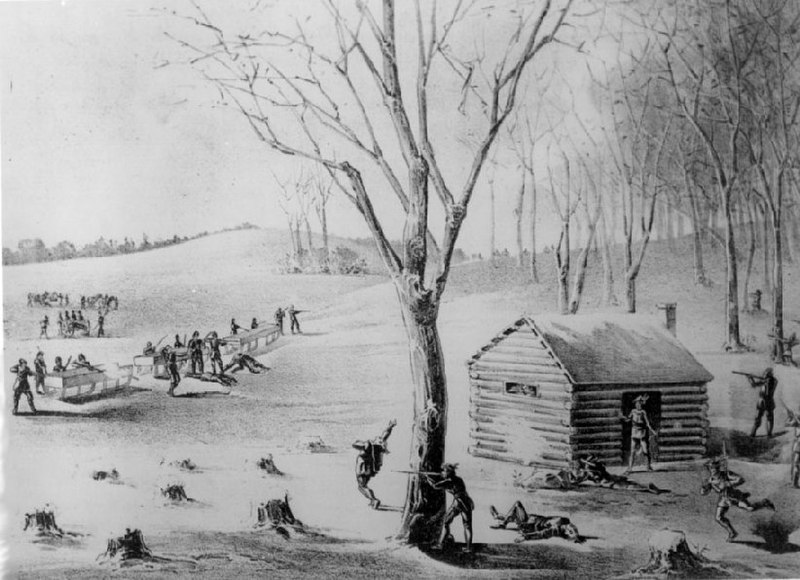

This led to the first battle known as the Battle of Duck Lake on March 25-26, which resulted in a Métis victory as the larger force of Métis and Cree led by Dumont forced the North-West Mounted Police and volunteers to retreat. After this defeat, the Canadian government forces retreated from Fort Carlton and prepared for the next assault.

By this time, Major General Frederick Middleton had arrived in Saskatchewan with thousands of troops. Middleton moved on to Batoche where he knew Dumont and Riel were based. The Métis entrenched themselves in Tourond’s Coulee (a ravine) and planned to trap Middleton. This would have potentially worked if not for an inexperienced Métis scout who accidentally made it known where they were encamped. Middleton remarked later that “[Métis] plans were well arranged beforehand and had my scouts not been well to the front we should have been attacked in the ravine and probably wiped out”.

Nonetheless, the result was still a Métis victory as the smaller but more experienced Métis force visited heavy losses upon the Canadian army, forcing Middleton to sound the retreat. This is what is known as the battle of Fish Creek.

The defeat

While the conditions for an uprising were actually quite favourable in 1869-70, a lot had changed by 1885. Ottawa now had large numbers of police, Mounties and militia in the area and could move large numbers of troops into the region in just 10 days. This is in stark comparison to the three months that it took to transport the Canadian Expeditionary Force to Red River in 1870.

In addition, while both the Métis and First Nations were yearning to fight back they were starved for supplies. Following the Battle of Fish Creek, Dumont’s forces had lost 55 horses and were almost clean out of ammunition. On the other side, while Middleton’s force was inexperienced, they had Gatling guns recently purchased from the Americans and were armed to the teeth.

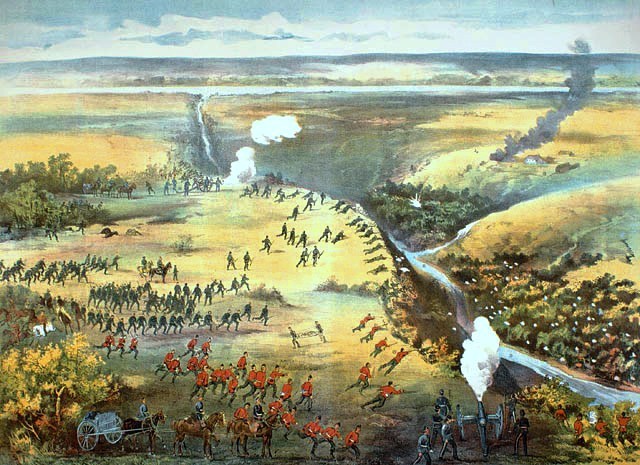

All of this led to the desperate final showdown at the Battle of Batoche which lasted for four days from May 9 to May 12, 1885. While the Métis fought valiantly, disabling a ship with a Gatling gun on it and holding a far superior force at bay, Middleton’s force of nearly 900 eventually overwhelmed the smaller Métis force which was out of ammunition. Following this, the various First Nations groups surrendered over the next two months.

It would be easy to point to the fact that the Métis had been weakened since 1870 and that the Canadian state was more equipped to transport troops to the region, and come to the conclusion that defeat was therefore inevitable. In fact, this is generally the way the story is told.

But things are not so simple. In 1885 there was widespread discontent and the unity of the Métis with the white farmers and the various First Nations groups was more possible than ever. If a coordinated and united uprising had taken place, the revolution still stood a good chance of success. However, a united revolutionary leadership was ultimately lacking.

Just like in 1869-70, there were differing class interests which weakened the movement from the inside. When the movement took a militant turn in the spring of 1885, more well-off bourgeois elements abandoned the movement. By the time of the Battle of Batoche, the forces of the revolution were quite meager. This was the situation with Métis businessman and founder of Batoche, Jean-Baptiste Letendre dit Batoche, and other bourgeois elements like Charles Nolin who dissociated themselves from the “revolutionaries.” Similarly to what took place during the Red River Resistance, the bourgeoisie were not prepared to go down the revolutionary road to achieve their demands.

In a revolution the question of leadership is of prime importance. Riel, while a point of inspiration, ultimately wavered and held the movement back at decisive stages. Riel was actually opposed to armed resistance to the Canadian government.

Similarly, the main First Nations leaders were actively trying to hold back their ranks. As mentioned previously, by 1876, the majority of First Nations leaders all signed treaties with the Canadian government in a vain hope to hold on to the little bit of land offered to them. Only chiefs Poundmaker, Badger and Young Chipewyan spoke against signing the treaties, with Poundmaker stating: “This is our land, it isn’t a piece of pemmican to be cut off and given in little pieces back to us. It is ours and we will take what we want.” However, they all ended up signing under pressure from prominent chiefs Mistawasis and Ahtahkakoop who were loyal to the Canadian government.

By 1884, while there was mass starvation among many First Nations, most of them were led by leaders who were subservient to Indian Affairs and the Crown. In the words of Howard Adams, “Indians obtained no relief from their chief, even when they elected him themselves, since the pressures exerted on them to elect subservient “Uncle Tomahawk” chiefs were enormous. These chiefs represented the ideology and policies of the Indian Affairs Branch and tended to be conservative and obedient servants to the Indian agents, helping to impose upon their people ideas and programs that would keep them in a colonized state.”

While some First Nations leaders like Poundmaker, Big Bear and Crowfoot started to organize in 1884, when push came to shove they stepped back from an open conflict with the Canadian state. Despite being asked by Riel multiple times to join forces, the First Nations leaders pledged neutrality during these events. But as the old adage goes, “you might not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.”

First Nations warriors were inspired by the courageous stand of the Métis and started to take matters into their own hands. Cree groups looted Fort Battleford, taking food and supplies on March 30 and attacking the town of Frog Lake on April 2. On April 15, 250 Cree warriors took Fort Pitt and on April 26, Cree groups looted HBC posts at Lac la Biche and Green Lake. On May 2, Cree and Assiniboine warriors scored a victory after being ambushed by 300 soldiers commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter at the Battle of Cut Knife. Though Poundmaker was opposed to it, his warriors planned to join the Métis forces at Batoche in mid-May 1885. Unfortunately, they were too late and by then the Métis had already been defeated.

Thus, instead of having a united movement of Métis and First Nations which could have stood up to and probably defeated Middleton’s forces, there were isolated and fragmented desperate outbursts.

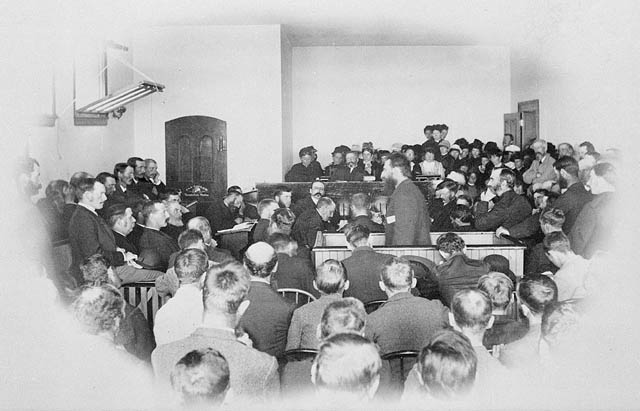

Three days after the Battle of Batoche, Riel turned himself in and Dumont fled to the United States. The history that followed is unsurprising. A jury of six white Anglo-Protestants and a judge appointed by Macdonald found Louis Riel guilty of treason and he was put to death by hanging on Nov. 16, 1885. The government had the ability to commute the death sentence but the ruling class had to send a clear political message: no revolutionary action would be tolerated.

Cementing the execution of Riel as a symbol of the oppression of francophones, MacDonald said his famous words about the Métis leader: “He shall hang though every dog in Quebec bark in his favour.” The response to this was huge in Quebec, with 50,000 marching in the streets of Montreal—the largest demonstration ever to be held in Canada up to that point. For his role in crushing the movement, Middleton was knighted by Queen Victoria and received $20,000 from the Canadian government.

The weak echo of a weak echo

We previously analyzed the rebellions of 1837-38 and called them “the weak echo of the American Revolution.” This was drawing a parallel to the situation in Europe, where Marx referred to the revolutionary wave of 1848 as the “weak repercussion” of 1789.

The meaning here is that during the classical epoch of the bourgeois revolution in Europe, the capitalists put themselves at the head of the movement against the feudal system, fighting for “liberty,” “equality”, etc. They rallied the masses behind them and struck blows against the aristocracy, the church, etc. The classic example of this is the Great French Revolution.

One of the reasons why the bourgeoisie appears more courageous in this period is that they are not yet fully conscious of their position in society. The class contradictions at the end of the 18th century in France had not yet developed far enough for the bourgeoisie to be more scared of the proletariat than the aristocracy.

As Marx explained, “In both revolutions [1648 in Britain and 1789 in France] the bourgeoisie was the class that really headed the movement. The proletariat and the non-bourgeois strata of the middle class had either not yet evolved interests which were different from those of the bourgeoisie or they did not yet constitute independent classes or class divisions.”

However, even in the French Revolution, the still-embryonic proletariat and the “non-bourgeois strata of the middle class” did at times push the revolution further than the capitalists actually were prepared to go. As Marx continues, “Therefore, where they opposed the bourgeoisie, as they did in France in 1793 and 1794, they fought only for the attainment of the aims of the bourgeoisie, albeit in a non-bourgeois manner. The entire French terrorism was just a plebeian way of dealing with the enemies of the bourgeoisie, absolutism, feudalism and philistinism.”

By 1848, the contradiction between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat was much more developed. This quickly threw the German and the French bourgeoisie into the arms of the counter-revolution and the same can be said of the bourgeois elements in Canada who were fighting for free trade and formal bourgeois democracy in 1837-38 in Upper and Lower Canada.

We see an even more pronounced example of this in 1869-70 and 1885, which were really a continuation of the same process. The big Canadian bourgeoisie had found an accommodation with Britain and had gained nominal independence. They didn’t want a revolutionary republic as they had found a comfortable position as the ruling class of Canada. However, many of the tasks of the bourgeois revolution remained incomplete—especially in the colony of the North-West Territory. While the Métis Resistance was objectively fighting for the interests of the bourgeois democratic revolution and its tasks in both the Red River and North-West Rebellions, the big Canadian bourgeois as well as the rising Métis and Anglo bourgeois in the North-West recoiled at the revolutionary implications.

The Métis and Anglo bourgeois recognized where their class interests lay and also sought an accommodation with the big Canadian bourgeoisie. So here we have a situation where the petty bourgeois of the North-West colony, like the Patriots before them, were fighting against the big and rising bourgeoisie for the completion of the tasks of the bourgeois revolution. Riel, Lepine, Dumont and the other leaders were betrayed as soon as the movement started taking serious measures. Some of the Métis leaders were even in league with the Canadian Party! In addition to this, while the petty-bourgeois leaders Papineau and Mackenzie at least were openly fighting for a revolution to create a democratic bourgeois republic, the leaders of the movement in the North-West were not even clearly fighting for that. Riel even swore allegiance to the Queen and rallied Métis troops to put down the Fenian invasion in 1871!

While the proletariat was still rather undeveloped in the North-West at this time, we also start to see this class contradiction within the movement express itself. In early May 1885, the Métis were camped out in Batoche. By this time, they had been abandoned by the bourgeoisie. In addition, First Nations chiefs had not heeded the call and they were isolated. On top of this, they were nearly out of supplies. Riel’s secretary Honoré Jaxon advocated ending private ownership of the land as a solution to the land question, which was the central question for the vast majority of people in the North-West. In response, Riel had Jaxon arrested as he feared that this would cause further divisions among his followers. This ended up being a vain endeavor, as there was no placating the bourgeois elements who jumped ship anyway and left Riel and Dumont high and dry to face the Canadian army under Middleton.

Riel and the other leaders were not consciously aware of what they were objectively fighting for. However as Marx said: “Just as one does not judge an individual by what he thinks about himself, so one cannot judge such a period of transformation by its consciousness, but, on the contrary, this consciousness must be explained from the contradictions of material life, from the conflict existing between the social forces of production and the relations of production.”

So the “rebellions” in Red River and in the North-West were basically a belated bourgeois democratic revolution which the bourgeoisie abandoned or conspired to crush. Objectively speaking, the movement around Riel needed to carry out the tasks of the bourgeois revolution, i.e. establish formal democracy, resolve the land question, liberation from imperialist domination, etc., but Riel and the other petty bourgeois leaders did not subjectively understand what they were fighting for objectively. The most enthusiastic supporters were in fact proletarian or poor farmers or hunters, but they weren’t a significant enough force to lead to a socialist revolution. Jaxon’s propositions were aimed at rallying these forces, but in a sense this was ahead of its time.

The struggle today

Today, there is an ongoing debate about the legacy of Louis Riel. While there has been an ongoing campaign to have Riel exonerated by the federal government, many Métis leaders are critical of this. In the words of Riel’s great-grandniece Jean Teillet, “Pardons or exonerations are not about justice but political expediency.” Manitoba Métis Federation President David Chartrand added, “The only thing a pardon and exoneration will end up doing is actually [to] exonerate and pardon Canada.”

With the federal Liberals exonerating Chief Poundmaker in 2019 for his role in the events of 1885 and apologizing to the Poundmaker Cree Nation, it is possible that they will use a cheap stunt like this to attempt to gain some political capital. However, we shouldn’t fall for what are essentially meaningless tokenistic gestures.

In the words of Gerald Morin, the former president of the Métis National Council, “Riel and many Métis people fought and died for a cause…The Métis are still a landless people in Canada.” Morin also said that “to put in place the justice and vision we’ve been fighting for…we don’t just want symbolic gestures.” We wholeheartedly support this sentiment. Métis people need real justice, not tokenistic gestures which allow the political elite to save face without costing them a penny.

Riel led a revolution. Yes, it failed, but this is the story of the vast majority of revolutions. The important thing is to learn why and to prepare for the future mass movements which are just around the corner.

While Riel’s steadfast supporters in 1869-70 and 1885 were drawn from the tripmen, the proletariat, poor farmers and hunters, these Métis proletarians were much too small and underdeveloped to lead the struggle towards the creation of a socialist society at the time. However, today the working class is the crushing majority of society.

This means that the possibility of winning real justice is more possible than ever. It’s up to us today to learn the lessons of the Métis revolution against the Canadian state, to carry on the struggle which Riel, Dumont, Lépine and others began and to bring real justice through the building of a socialist society in which all peoples can be liberated from oppression and exploitation.

Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four